THE FUTURE OF CITIES

What’s ahead for urban downtowns still struggling to recover from the pandemic?

The answer to this question is likely still a few years away, at least when it comes to professional activity. “Foot traffic in downtown offices has gradually been increasing over time, but I don’t think we’re at equilibrium yet,” says Jessie Handbury, Wharton associate professor of real estate. “We’re also not yet at equilibrium in how foot traffic is arranged. In thinking about the vibrancy of commercial centers, I expect there to be certain blocks and properties that do well and some that end up vacant, potentially to be redeveloped.”

Among the factors that will determine which blocks and buildings win in the anticipated competition for tenants, Handbury foresees a coordination of sorts among businesses. “At the moment, everywhere is looking a little bit flat, but I think there will be some clustering, which is going to take some time because of the lengths of leases tenants have signed,” she says. “Tenants that are going to be re-signing leases will be looking for buildings that have a lot of amenities and that are supported by restaurants, gyms, and other locations.”

For the firms that re-sign their leases or move into new downtown space, Handbury also anticipates a level of likeness — what she and Dean’s Chair in Real Estate Professor Gilles Duranton point to as the creative class in their new paper “COVID and cities, thus far.” Those businesses include advertisers, entertainment companies, and even researchers. “Any type of firm that leans on serendipitous interaction, whether it be bumping into each other or a random knock on the door, is going to want their workers still in offices,” says Handbury. The authors expect dropping rent prices to enable this type of migration for companies that may have previously been outbid for the space.

As for retailers, Barbara Kahn, the Patty and Jay H. Baker Professor of Marketing, is tracking a continuation of pre-pandemic trends. “We are seeing people go back to stores, but the shopping experience has firmly changed to more of an omnichannel experience,” she says. “COVID accelerated that notion.” Kahn points to digital-first brands like Allbirds and Glossier, which have continued to set up shop in cities since the onset of the pandemic. “They’re opening physical stores as a customer-acquisition strategy, because it’s now cheaper to open a store than it is to buy digital advertising to introduce new people to their brand,” she says. “The cost of advertising online has gone up, while rents have gone down and leases have become shorter. It’s easier for a new brand to open a physical store to create some buzz.”

Cities are also being impacted by bigger-picture shifts in the composition of brick-and-mortar locations nationwide. “You’re seeing a lot more services like health clinics, pet stores, and nail salons,” Kahn says. “Many of the stores that are opening up aren’t traditional businesses focused on products, because a lot of that is being purchased online now.”

ISO WORKPLACE NIRVANA

What can firms do to keep employees happy?

“Organizations and managers need to be able to give employees more flexibility than in pre-pandemic times but at the same time provide opportunities and events that draw people together, so that they don’t lose a sense of community and culture. This often means more work for the manager, and organizations need to also be aware of not burning out their middle managers in these attempts.”

—Nancy Rothbard, Wharton School deputy dean, professor of management, and David Pottruck Professor

OUR AI OVERLORDS

What impact will ChatGPT have on our work and our world at large?

The short answer: We don’t quite know yet. “The floodgates have been opened with this release,” says Ethan Mollick, associate professor of management and Ralph J. Roberts Distinguished Faculty Scholar. Launched in November, ChatGPT is an advanced chatbot created by OpenAI that can analyze data, generate code, and write emails, memos, and more in a matter of seconds. It can even pass an MBA exam, as Christian Terwiesch, chair of the operations, information, and decisions department, found out when he administered his own test to the tool, drawing international headlines earlier this year. The launch has spurred an arms race among tech giants, with firms such as Microsoft and Salesforce integrating the chatbot software into their products and Google working to introduce so-called “generative artificial intelligence” to its own lineup.

The short answer: We don’t quite know yet. “The floodgates have been opened with this release,” says Ethan Mollick, associate professor of management and Ralph J. Roberts Distinguished Faculty Scholar. Launched in November, ChatGPT is an advanced chatbot created by OpenAI that can analyze data, generate code, and write emails, memos, and more in a matter of seconds. It can even pass an MBA exam, as Christian Terwiesch, chair of the operations, information, and decisions department, found out when he administered his own test to the tool, drawing international headlines earlier this year. The launch has spurred an arms race among tech giants, with firms such as Microsoft and Salesforce integrating the chatbot software into their products and Google working to introduce so-called “generative artificial intelligence” to its own lineup.

ChatGPT’s robust range of capabilities raises the question: Could it replace our jobs, as OpenAI’s CEO has suggested? “That’s very possible, but we don’t have a strong sense yet,” says Mollick. “Historically, new technologies don’t replace jobs. But whether that’s true in every case is not always clear.” To get a better sense of the implications, Mollick suggests new users take the tool for a test run: Prompt it to do key tasks of your work and see firsthand how it handles them.

Rather than replace workers, ChatGPT could simply make them more efficient. “Depending on the field, people are reporting time savings between 30 percent and 80 percent,” says Mollick. “I always tell people to spend some time practicing with it. You need to learn its language in order to prompt it properly. For example, you could tell it to write in a certain style or make a specific paragraph more interesting. You kind of need to program it. That’s the key.”

For all the technology’s strengths, there are also some obvious shortcomings, including the accuracy of its responses, as recent trial runs by the New York Times and other media outlets made clear. “It lies frequently and well,” says Mollick. “You have to be aware of the limitations.”

Mollick, who regularly shares his thoughts on AI advances in his popular One Useful Thing newsletter, has also combined ChatGPT with other AI tools that can generate audio and video. The result: a deepfake of himself that he created in just a few minutes. “It is trivial now to do that,” he says. “A lot of technologies are converging at the same time in complicated and sophisticated ways. We have to be ready for a world that’s getting much weirder, much faster.”

FAIR SHARES?

Legislators have taken aim at share buybacks recently. Is this renewed scrutiny merited?

“This issue is tied to another debate: Who is your duty to as the board of a public company? Some people take a broader view that your duty extends beyond the long-term value for shareholders. In weighing other constituencies, share buybacks could be seen as giving money to shareholders when it could be used for investing in new projects or paying employees more. You can certainly point to CEOs who cared about their short-term stock price over long-term investment, but to view it as endemic to public corporations is a bit of a stretch. It comes down to: How much do you trust management to invest when there’s an investment to make and to give capital back when there isn’t?”

—David Musto, director of the Stevens Center for Innovation in Finance and Ronald O. Perelman Professor in Finance

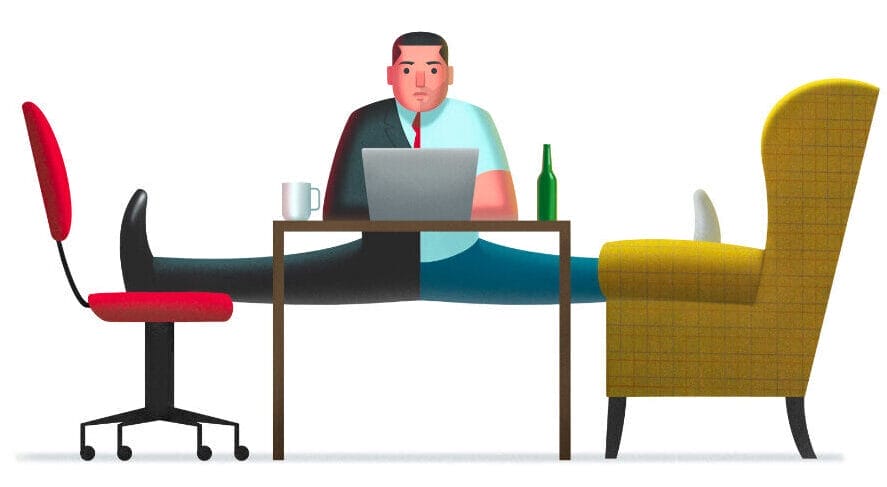

THE EVOLVING WORKPLACE

Who will win in the tug-of-war over fully remote, hybrid, and in-office work?

“I think the tug-of-war only started recently,” says Peter Cappelli, management professor, George W. Taylor Professor, director of Wharton’s Center for Human Resources, and author of The Future of the Office. “Employers were trying to bring everyone back starting in the summer of 2020, but each wave of a new COVID variant kept people at home. At some point, employers just stopped planning for a return.”

“I think the tug-of-war only started recently,” says Peter Cappelli, management professor, George W. Taylor Professor, director of Wharton’s Center for Human Resources, and author of The Future of the Office. “Employers were trying to bring everyone back starting in the summer of 2020, but each wave of a new COVID variant kept people at home. At some point, employers just stopped planning for a return.”

As work-from-home arrangements stretched on, they became the status quo, says Cappelli, who adds that the labor market’s subsequent tightening prevented companies from enacting full return-to-office policies. “Employers thought they couldn’t hire if they made people come back,” he says.

Now, Cappelli expects some employers to push harder for a full return. “They are certainly making a louder case that it is important for their business to do so,” he says. “The big question, which still remains something of a puzzle, is why the job market ultimately continues to be so strong. The idea that it is because so many people did not come back to work after the pandemic is not true: The trend to lower participation among older individuals was under way long before the pandemic and just continued.” One possibility, he offers, is that the U.S. has experienced little productivity growth in the past few years. “The slower productivity growth is,” says Cappelli, “the more workers are needed to do the same output.”

The professor suggests that even for workers who remain permanently remote or hybrid, home and in-office experiences may begin to look more similar in at least one respect, if they don’t already. “Looking back, I did not anticipate the growing use of ‘tattleware’ to monitor what remote workers are doing at home,” says Cappelli. “I suppose this was inevitable for employers who wanted employees back in the office and didn’t think they could force them back. So they try to bring monitoring of the office to the home.”

POLITICISIZING ESG

What are the ramifications of political blowback over companies’ environmental, social, and governance efforts, such as states cutting ties with money managers that factor ESG into their investment decisions?

“Pursuing the integration of ESG factors into investment and financial analysis should not be ideological but rather just good economic or financial decision-making. Sadly, like the right to vote, the right to calculate returns on investments and resource allocations has become politicized where those decisions involve environmental, social, or governance criteria.

“In the short term, the direct economic consequences of this legislation and regulation are the shifting of state and municipal bond issuances from the biggest, most efficient financial institutions, which believe in the materiality of ESG factors, to smaller, less well-resourced institutions that don’t or that lack the capacity to do so. The cost of this transfer, according to research by Wharton professor Daniel Garrett, is already about $300 million to $500 million in the state of Texas alone and likely exceeds $1 billion if proposed policies are enacted in other states where they have been introduced.”

—Witold Henisz, vice dean and faculty director of the ESG Initiative and Deloitte & Touche Professor of Management

THE CRYPTO CONUNDRUM

Can anyone predict the future of cryptocurrency right now?

“The crypto space changes so rapidly that making predictions is always dangerous,” says Kevin Werbach, chair of the Legal Studies and Business Ethics Department and the Liem Sioe Liong/First Pacific Company Professor. “It’s also crucial to distinguish cryptocurrency trading markets, which have a track record of booms and busts, from other applications of blockchains and digital assets. The fundamental vision of blockchain technology is about decentralization and disintermediation. Yet amid the frenzy of excitement in the crypto bull run starting in 2020, many investors turned to centralized and poorly regulated services like FTX, Celsius, and BlockFi.”

As for where the blockchain and digital-asset industry goes from here, Werbach sees the absence of an explicit legal framework in the U.S. as a key challenge. “In the current situation, it’s almost impossible to disentangle speculative activity, sometimes involving questionable or outright illegal practices, from functional innovations,” he says. “We need a solid foundation for trust in digital-asset markets before the bulk of individuals and institutions truly become comfortable.” Given the country’s current political climate, he says, the chances for legislation look dim in the short term.

As for where the blockchain and digital-asset industry goes from here, Werbach sees the absence of an explicit legal framework in the U.S. as a key challenge. “In the current situation, it’s almost impossible to disentangle speculative activity, sometimes involving questionable or outright illegal practices, from functional innovations,” he says. “We need a solid foundation for trust in digital-asset markets before the bulk of individuals and institutions truly become comfortable.” Given the country’s current political climate, he says, the chances for legislation look dim in the short term.

Still, Werbach expects some progress in the next year. For one, a decision regarding a suit filed in 2020 by the Securities and Exchange Commission against cryptocurrency company Ripple seems imminent. The suit could provide more clarity on when cryptocurrencies are considered securities in the U.S., which would have important implications for regulation. Separately, the SEC and other regulators are working on a framework for stablecoins, which serve as a bridge between digital assets and the established financial system. “I’m hopeful that U.S. banking regulators, who have turned very critical of digital assets in the wake of FTX, will work to offer a path to compliance for those firms willing to make the investments in risk management,” says Werbach. “But I’m not very optimistic at the moment.”

THE COST OF CARE

Is there a sensible starting point for tackling sky-high health-care costs?

“We’ve got a really sticky, intractable problem. We could take various approaches, but one question is whether lawmakers will stop kicking the can down the road. Every few years, the parties will coalesce and figure out who’s the new bad guy to go after. In the ’90s, it was health maintenance organizations. Then it was group purchasing organizations and later Medicare Advantage plans. It’s since become pharmacy benefit managers. All four of them are intermediaries. They’re usually less understood, so people go after them. But that’s not where the money is spent. Roughly two-thirds of all health-care spending happens between hospitals, doctors, and drug companies. And among the things that are rising in the federal budget are Medicare and Medicaid. An obvious route to take is controlling drug spending under the Medicare program, which the Biden administration has just started to do. We need some more political will to even attempt to tackle this, and we need to do it on a bipartisan level. We just have to bite the bullet at some point.”

—Lawton Robert Burns, professor of health-care management, professor of management, and James Joo-Jin Kim Professor

THE TROUBLE WITH SOCIAL MEDIA

Where is the online content moderation debate headed in the U.S.?

If there’s one thing most people agree on when it comes to the wild world of social media, it’s that something needs to change. But that’s where the agreement seems to stop. “There is a lot of variation in terms of what people want to see or what they find objectionable,” says Pinar Yildirim, associate professor of marketing and associate professor of economics. “And then there’s the matter of what kind of actions they are comfortable with platforms taking.”

If there’s one thing most people agree on when it comes to the wild world of social media, it’s that something needs to change. But that’s where the agreement seems to stop. “There is a lot of variation in terms of what people want to see or what they find objectionable,” says Pinar Yildirim, associate professor of marketing and associate professor of economics. “And then there’s the matter of what kind of actions they are comfortable with platforms taking.”

Perhaps most consequential in determining the path forward are a complicated array of new laws passed by U.S. legislatures and legal challenges wending their way through the courts. At press time, Supreme Court cases focused on YouTube and Twitter could fundamentally narrow Section 230 protections that shield social media companies from liability for user-generated content. The court is also poised to hear cases concerning laws passed in Florida and Texas that have been crafted to challenge platforms’ moderation of political speech. Those laws, if upheld, would have implications for platforms’ ability to regulate and remove users.

No matter the outcomes, Yildirim sees a clear business case for platforms themselves to be particularly diligent about extreme speech at a time when many moderation efforts are in turmoil amid layoffs, ownership changes, and more. “If you allow extreme accounts to speak freely, that doesn’t mean you are maintaining freedom of speech for everybody,” she says. “Inaction does not create more diversity and freedom to express opinions. Based on scientific evidence, you are actually able to increase the engagement of other users by removing offensive comments. That seems to allow others to feel more comfortable, and their engagement increases significantly.”

Yildirim also still sees advertisers as one of the most influential forces for informing tech’s self-policing. “Since Twitter changed hands, we’ve seen advertisers pulling out because they are concerned about the content moderation policies and what kind of platform that might turn Twitter into,” she says. According to a February report from CNN, about 625 of Twitter’s top 1,000 advertisers had pulled paid ads from the service. Yildirim likens these moves to advertisers historically flexing their financial might with certain cable news outlets. “The same idea applies on social media,” she says. “Big advertisers are not going to want to put their brand name next to content they don’t support.”

CHAIN PAINS

What’s the supply chain factor that we most need to pay attention to now?

“There’s a lot going on that the public doesn’t relate to in the same way as COVID, wars, and weather disasters, because it isn’t covered in the news. The biggest source of supply chain disruptions is actually factory fires. The other part of the story that gets missed is supply mismatch from demand surges. We saw that with toilet paper and masks during the pandemic: a sudden demand for residential supplies and very little demand for commercial supplies. The daily life of a supply chain manager is an onslaught of cuts and bruises— dealing with an endless array of all kinds of things.”

—Marshall Fisher, UPS Professor and professor of operations, information, and decisions

Published as “Ask Me Anything” in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Wharton Magazine.