A woman in my business school class, Lisa Stephens, had a five-year-old daughter who fell in the kitchen one Saturday morning, gashing her forehead on the sharp corner of the kitchen table.

The child, Aubree, was hysterical. The child’s grandfather, Lisa’s father, was hysterical. Aubree clearly had to go to the hospital to get stitches. But she refused to go, clinging to the table for dear life. No one could pry her little fingers off the kitchen table. Lisa was about to become hysterical, too, when she suddenly stopped. She said to herself, “Wait a minute. I’m taking a negotiation course. I’m going to negotiate this.”

So Lisa walked over to her daughter and touched her gently on the arm. “Does Mommy love you?” Lisa asked. “Yes,” her daughter sniffled, calming down.

“Would mommy do anything to hurt you?” her mother asked. “No,” her daughter said.

“When we get to be big people, do we have to do things sometimes that we don’t like to do?” her mother asked. “Yes,” Aubree said.

“Mommy has stitches,” Lisa said. She showed her scar. “Granddaddy has stitches,” she said. Lisa’s father showed his scar. And within five minutes, her daughter let go of the table and walked to the car by herself.

Here are some things that we know for sure about this event.

First, Aubree’s refusal to go to the hospital was entirely irrational. It was in Aubree’s interest to go to the hospital, and get there quickly. But, as in millions of negotiations every day, she wasn’t being rational.

The second thing this story shows is that we must start a negotiation thinking about the pictures in the heads of the other party. Lisa’s goal was to get Aubree to the hospital without traumatizing her further. The mother realized that the picture in Aubree’s head was, “I’m hurting and alone. I need love.”

So, having considered, “What are my goals?” and “Who are they?” The mother thinks, “What will it take to persuade Aubree?” So Lisa asks, “Does Mommy love you?” The question shows her daughter that her mother understands that her daughter needs love. Lisa draws her daughter out as Aubree answers the question.

Lisa then realizes her daughter is probably thinking, “Okay, Mommy loves me, but I’m in pain.” So her mother asks, “Would Mommy do anything to hurt you?” And Aubree realizes that her mother is thinking about her daughter’s pain, too.

This whole process is incremental, starting from the mother thinking about the pictures in the child’s head to achieving the mother’s goals. It doesn’t take very long–it happens step by step. And in the end, within five minutes, Aubree walks to the car of her own free will, rather than being dragged kicking and screaming—a more common and more traumatic way to do it.

In sum, what Lisa gave Aubree was a series of emotional payments. They directly addressed Aubree’s fears and showed her that her mother understood. In other situations, the emotional payment could be an apology, words of empathy or a concession. It could be just hearing someone who is upset.

Emotional payments have the effect of calming people down. They get people to listen, and be ready to think more about their own welfare. They start from irrationality and move people, little by little, toward a better result, if not a rational one.

***

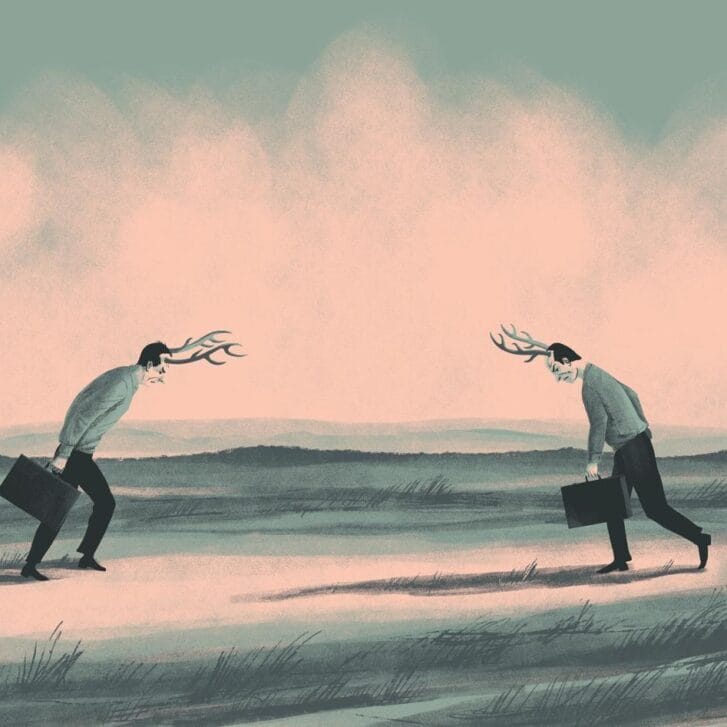

Emotion is the enemy of effective negotiations and of effective negotiators.

People who are emotional stop listening. They often become unpredictable and rarely are able to focus on their goals. Because of that, they often hurt themselves and don’t meet their goals. Movies often show scenes of impassioned speeches, suggesting these are highly effective. Whether that is realistic or not depends on whether the speaker is so emotional that he or she is not thinking clearly.

Emotion, used in the context of negotiation, is when one is so overcome with one’s own feelings that he or she stops listening and is often self-destructive. The person can no longer focus on his or her goals and needs. Empathy, by contrast, is when one is focused on the feelings of the other person. It means being compassionate and sympathetic.

In other words, emotion is about you. Empathy is about the other party. Empathy is highly effective. Emotion is not.

Genuine displays of emotion—love, sadness, joy—are of course part of life. But it’s important to recognize that these emotions, while real, reduce listening, and therefore are not useful in negotiations where processing information is critical. People feeling such emotions are almost always absorbed in the moment, for solace or gratification. The long-term goal of reaching the best outcome, and the broader world, often recedes. The feelings can be needed and important, but not effective to reach well-considered results. Indeed, emotions can push people to do things they later regret.

The emotional strategies that I teach are designed to enhance relationships both personally and in business. I believe it is possible to be dispassionate and compassionate at the same time.

When people get emotional, here is what happens. Instead of focusing on goals, interests, and needs and effectively communicating, emotional people focus on punishment, revenge, and retaliation. Deals fail, goals are unmet, judgment is clouded, and people don’t meet their needs. Emotion destroys negotiations and limits creativity. Focus is lost. Decision-making is poor. Retaliation often occurs.

Emotion in negotiation has received increasing attention since 1990. Researchers, teachers, and practitioners began to realize one had to address the emotional side of people, not just the rational side. The results of this attention have generally been mixed and not always helpful.

For example, there has been a trend suggesting that it is okay to feign emotions such as anger or approval to get others to do what you want. This is, of course, dishonest, and usually manipulative. The tactic aims to get other people emotional so they are scared or flattered into doing something they would not otherwise do, and which too often is not in their best interests.

For example, there has been a trend suggesting that it is okay to feign emotions such as anger or approval to get others to do what you want. This is, of course, dishonest, and usually manipulative. The tactic aims to get other people emotional so they are scared or flattered into doing something they would not otherwise do, and which too often is not in their best interests.

The tactics are called things like “strategic emotion,” “false-positive feedback,” “a display of fury to extract a concession,” “on-demand emotional expression,” “tactical emotions,” “impression management,” “strategically angry,” and “emotion manipulation.” These are variations of “good cop, bad cop;” they destabilize situations and make them unpredictable; they often aim to get the other party to make a mistake, such as disclosing information that can be used against them.

Most of the advice on using emotion to manipulate a negotiation doesn’t consider the long-term effects on the relationship, which usually ends when the manipulator is found out. Credibility and trust take a big hit. If you find the other party displaying false emotions just to get you to act in a certain way, I suggest that you never deal with them again if you can help it.

Some people point out times when they have used emotion as negotiation tools and they have worked. The problem is that they are risky and unpredictable in terms of the results, and cynical and untrustworthy in terms of attitude. They destroy relationships. Demands to “take it or leave it” increase rejection rates, studies show. People perceive them as unfair and will sometimes reject good deals out of spite. Only half as many offers are accepted when negative emotion is used.

***

Let’s look more specifically at what the introduction of emotions often does to a negotiation.

First, they destabilize the situation. You are much less sure of how the other person is going to react. The outcome is less predictable when the parties are emotional.

Emotion reduces people’s information-processing ability. That means they don’t take the time to explore creative options. They don’t look at all the facts and circumstances. They don’t look for ways to expand the pie. As a result, they don’t get more. In fact, emotional people, studies show, care less about getting a deal that meets their needs than about hurting the other party.

It is true that positive emotions have been shown to increase creativity and the likelihood of reaching an agreement. But such negotiations are often conducted at a pitch and with a fervor that are risky. You’ve seen an ebullient group suddenly turn on someone or something that had previously been the object of their affections. That kind of instability should worry you. Try to conduct negotiations that are calm and stable. Warm feelings, perhaps, but laced with solid judgment. The emotional temperature needs to come down if you want to meet your goals and solve thorny problems.

What about the strategy of good cop, bad cop? This is a favorite tool that participants in negotiation courses say they use. The police use this tactic to try to destabilize a suspect by causing emotion. They hope the suspect will make a mistake and make an admission (against their goals and interests). So, yes, anger and emotion work in a situation where you want to try to harm the other party. But unless you want to harm the other party and get them to make a mistake, you probably don’t want to use anger as a negotiation tool.

Another problem with using emotion on purpose is that the more you use it, the less effective it becomes. If you raise your voice or shout once a year, it can be very effective. If you do it once a month, you become known as “the screamer,” and you lose credibility. This applies to walking out of negotiations as well.

A tone change is fine once in a while. If you are normally quiet, every once in a while you might raise your voice. If you are normally a pretty loud person, once in a while you might be especially quiet or soft-spoken. But such tactics must be well-thought-out and measured.

Negotiations are more effective when they are stable and predictable.

***

So how do you control emotion in a negotiation?

If you are emotional, you are no good to anyone in a negotiation. If you start to get emotional, stop! If you can’t, perhaps you aren’t the right negotiator, at least not at the time. If you try to negotiation when you are upset, angry or otherwise emotional, you will lose sight of your goals and needs. And you will make yourself the issue.

Lower your expectations. If you come into a negotiation thinking that the other side will be difficult, unfair, rude or trying to cheat you, you won’t be likely to have dashed expectations—and you won’t be as emotional. When you lower your expectations of what will take place in a negotiation, you will be rarely disappointed—and you might be pleasantly surprised. Dashed expectations are a big cause of emotion.

So you can control your own emotions. Dealing with the emotions of others can be trickier.

The first step toward dealing effectively with the emotions of others is to recognize when they are being emotional. The key is whether the other person is acting against his or her own interests, needs and goals. You have probably watched people do exactly the opposite of what benefits then. You ask yourself, “What’s wrong with them? Can they see this won’t help them?”

They can’t. They have lost focus on their goals and needs. They are being emotional. They aren’t listening clearly. To persuade them, you have to begin by increasing their ability to listen. That means you have to calm them down. You have to become their emotional confidante. Try to understand their emotions. What gave rise to them? What can you do to calm them down?

You have to figure out what kind of emotional payment they need.

***

Today, more than a dozen years later, Lisa Stephens and Aubrey still talk about the extraordinary experience they had in the kitchen that day. “We see the small scar on Aubree’s forehead and remember the twelve stitches and how we handled it together,” said Lisa, now a senior manager for a major consulting firm in Washington, D.C. “Not a day goes by that we don’t use the negotiation tools to improve our lives.”

Lest you think this anecdote is the exception: I had an executive in one of my programs at Wharton named Craig Silverman, a financial advisor on Long Island. Craig went to a local medical laboratory one day for a routine blood test. In the next room was a young girl, about five years old, screaming at the top of her lungs “as if she was being tortured,” Craig said. She was supposed to get a blood test, too, but she wouldn’t let the nurse stick her arm with the needle. Her mother, soon joined by Craig’s nurse, was holding the girl down, while a second nurse was trying to stick the needle into the girl’s arm. It was a nightmare of a scene.

Craig, remembering the story of Lisa and Aubree, decided to be of assistance. He went to the girl’s room and asked her mother’s permission to talk with the girl, which he received. “Look at me,” he said to the girl. “Do you think your mommy loves you?”

“Yes,” the girl said.

“Do you think your mommy would do anything to hurt you?” Craig asked.

“Do you think your mommy would do anything to hurt you?” Craig asked.

“No,” the girl said.

Craig went through the entire litany, with some variations, of what I described at the beginning of this piece, including, “Don’t you want to get better?” and then, when the girl had calmed down a bit, “The doctor can’t make you better unless they do this test.” Within two minutes, he said, the young girl calmed down and was ready for the needle.

“Her mother and the nurses looked at me like I was some kind of magician,” Craig said. “Where did you learn that?” they asked. I am happy to say he referred them to my book.

This piece was excerpted from Stuart Diamond’s Getting More: How to Negotiate to Ahieve Your Goals in the Real World, published by Random House/Crown Business. For more information, visit www. gettingmore.com