The organizers of the panel purposely brought together a roundtable that would generate sparks. They succeeded in getting more than an hour of back-and-forth, intelligent and informing discussion during “The High Costs for Cancer Care,” an event held on Wharton’s campus in mid-September. Given the relevance of the topic, the subject took on a broader debate about the nature of the U.S. health care system.

Indeed, the roundtable took that approach from the get-go when moderator Arnold “Skip” Rosoff, W’65, a professor emeritus of legal studies and health care management at Wharton and professor of family medicine and community health at Penn’s School of Medicine, asked his first question about “distributive justice” and the best form of health care delivery.

Ethicist and consultant Jennifer Dreyfus, WG’84, responded first. Relying on market forces to operate like invisible hands on the current American health care system would not work, she said. People cannot make good decisions, she explained, because they do not have adequate information. On the other hand, an “egalitarian” system with equal health care for all would not work either.

Medical care for cancer appears to represent the worst of both worlds. She cited a recent Institute of Medicine study that concluded current cancer care is neither patient-centered, coordinated nor evidence based.

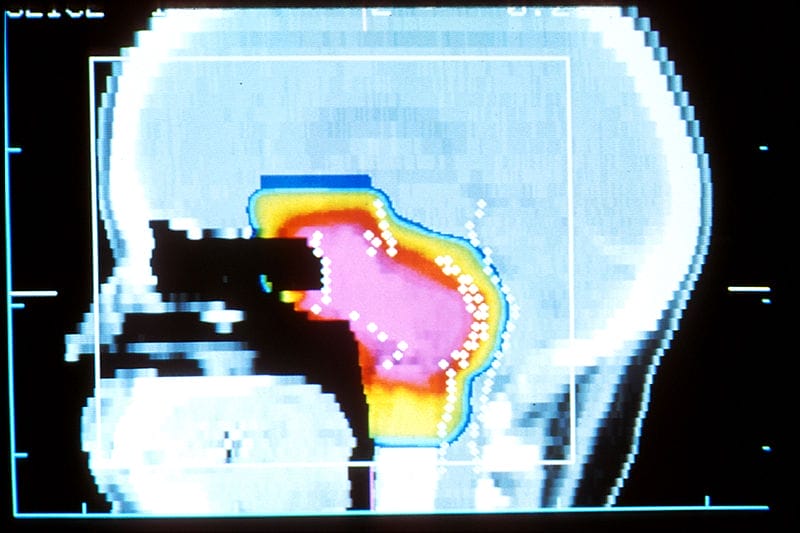

Take the proton beam therapy made famous by countless TV commercials for the few hospital systems that offer it. It is known in health care as the bazooka used to kill a mouse. At issue is that the intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) treatment more commonly used to irradiate cancer cells is just as effective against the most common cancers. Proton beam treatments, though, are twice as expensive per treatment.

Tying back to that bigger picture of the whole U.S. health care system, Dreyfus explained that what is at issue is the allocation of limited resources with fairness, equity and patient autonomy in mind.

Yet the answer to that resource allocation problem isn’t—as often posited—that using lower-tech solutions when efficacious is the way to lower overall health care expenditures. Data does not support it, said Dr. Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes and an attending physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“It seems to me the game is rigged,” he concluded.

The rigging is done by federal and state laws that mandate that health care payers—like Medicare, employers and insurance companies—pay the costs for cancer treatments that pharmaceutical companies demand.

“There’s absolutely no downward pressure,” Bach said.

Perhaps that is not so terrible in the long run, though. Spending could be what is needed to drive innovation in treatments. Scott Harrington, Wharton’s Alan B. Miller Professor of Health Care Management, provided an economist’s point of view, as well as his personal take. He asked rhetorically if most people would be willing to pay generously for cancer care if its effects were moderate at best. He personally would.

The current approach has equaled $25 billion spent annually on oncology drugs in the U.S. alone—$70 billion worldwide. The direct cost of cancer in the U.S. was estimated at $125 billion for 2012 and projected to grow to $173 billion by 2020.

“There is every reason to think that the spending growth will be associated with enormous value in the years ahead,” Harrington said.

The Wharton Health Care Management Alumni Association, a member of the Wharton Clubs Network, sponsored “The High Costs of Cancer Care.” Other participants included Peter Fishman, WG’07, ex-Novartis manager of global pricing strategy and government policy, and Dr. Joseph Leveque, WG’92, vice president at Bristol-Myers-Squibb, U.S. Medical–Oncology.