Pete Fader felt his senses overload as he walked through the Manhattan offices of recording giant Bertelsmann Music Group. The spacious, bright space was hung with framed, poster-size blow-ups of album covers by an eclectic mix of artists, from Elvis to the Backstreet Boys. Tables were buried under stacks of billboard, Rolling Stone and Variety magazines, multiple televisions pounded out the latest hits on VH1 and MTV, and unidentifiable Rock music streamed from almost every employee’s desk. “What an unusual place for a business school professor to be,” Fader recalls thinking.

It was 1998, and Fader had come with high hopes. He’d built some diagnostic forecasting models the likes of which the music industry had never seen, and was excited to share “the answer” to understanding years of languishing sales and profits with one of BMG’s senior vice presidents.

The VP, an older man dressed in the trendy garb of his youth-driven industry, led Fader into his office, a smaller version of the pulsating world he’d just walked through. The men sat down and the VP asked Fader a seemingly innocent question: “What kind of music do you listen to?”

“I thought he was making small talk, but the conversation kept going in that same direction,” Fader says. “I had no idea I was being judged by my tastes in music. I expected to be asked about my experience and credentials – the kinds of things consultants are typically asked during a first meeting. But this BMG guy really didn’t want to talk about anything that resembled formal business analysis.” As Fader would learn after many such meetings with industry executives, the music industry marches to the beat of its own drummer.

Music is a creative industry, Fader would be told by the BMG executive, that can’t be marketed like laundry detergent. Each and every album is one of a kind, its own brand, and can’t be fit into a larger pattern. It was a refrain that Fader would hear again and again as he made his rounds through the industry.

“I would go to a meeting and tell them, ‘Just give me some of your data and let me show you,’” says Fader. “And they would sit me down and say, ‘Well, you’re a smart guy, but you don’t understand this industry — it’s not like selling grocery products. It’s a people business. It’s about forming a unique relationship between an artist and a music lover.’ But in my mind I knew this was crazy, because I had looked at the data for dozens of albums across several genres and some very consistent sales patterns kept emerging over and over again.”

“They have basically built a moat around themselves to avoid dealing with genuine business issues. They say, ‘This is how we’ve done things for all of these years, and this is what has made this industry great.’ So part of it is just inertia. But part of it is fear, because they don’t know how to perform the kinds of analyses that I am suggesting, and they don’t want to lose control. They don’t want MBA types coming in and treating music like a regular business. This is all understandable, but is also contrary to what the shareholders of these companies are demanding,” Fader says.

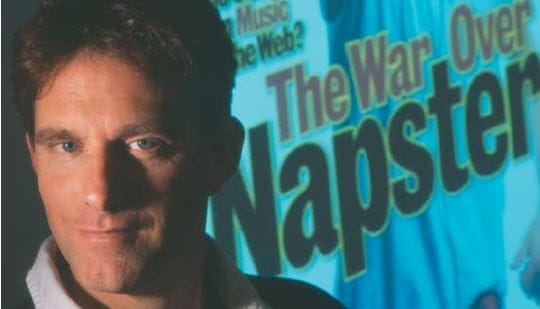

In Praise of File Sharing

Since his first meeting five years ago, Fader has continued to challenge the strongly held beliefs of dozens of music industry leaders. In the process, Fader has morphed from a little-known marketing research specialist, content in his “narrow packaged-goods world,” to a leading critic of the music industry, going so far, in July 2000, to serve as a key expert witness on behalf of Napster, the peer-to-peer filesharing service. During and since the Napster trial, Fader has argued that trading music files over the Internet, a practice the industry believes it loses $3.5 billion a year to, can actually boost sales in the long run. Some of his recent research (such as a study he co-authored, called “Using Advance Purchase Orders to Forecast New Product Sales”) uses complex statistical methods to understand how factors such as radio airplay and other forms of early publicity, including filesharing, can drive album sales.

“Generating buzz is a good thing, and filesharing is like a preview for a movie. It’s a tease without giving the whole movie away,” Fader says. “There’s a big difference between an MP3 music file and a complete CD, and most music fans realize this. Even if that means losing some sales to filesharing, it’s so important to spread the word that the net effect is generally positive for the industry.”

Rap artist 50 Cent, for example, was a relative unknown prior to the release of his debut CD in early 2003. “But a few of his songs leaked out over the Internet a few months prior to the album’s release, and his popularity exploded,” Fader says. “The record label got worried, saying that people were stealing the songs, and moved up the album launch by a few weeks to try to stem the flow.” In its first week in distribution, the album broke the record for retail sales by a new artist. “The obvious conclusion is that the files floating around were generating buzz and generating the sales,” Fader says. “But what did the industry say? ‘This filesharing is a terrible thing. We can’t imagine how many additional sales we would have had if the filesharing hadn’t been going on.’”

Other recent research supports Fader’s view. A 2002 report from Forrester Research saw “no evidence of decreased CD buying among frequent digital music consumers.” The study’s author cited the economy and surging DVD and video game sales as more likely causes, saying, “There’s no denying that times are tough for the music industry, but not because of downloading.” But the music industry has rejected this study and others that have drawn similar conclusions, responding to the filesharing issue by creating technological barriers to downloading and filing lawsuits against downloaders.

Fader, who has spent most of his 17 years on the Wharton faculty using behavioral data to understand and forecast customer behavior for grocery products, never imagined becoming a music industry gadfly. “I had always been happy to sit in my ivory tower office, messing with numbers for soap and toothpaste,” he says. But when a couple of his MBA students brought Fader some data on album sales, he saw sales patterns that mirrored those for new consumer packaged goods launches. “What I saw was a very sexy industry that needed some fresh insights,” Fader says. “I felt I had some interesting frameworks for them to consider. And unlike packaged goods, where most of the action is in repeat purchasing, in music, you never buy the same album twice. The numbers are much cleaner and easier to work with than other industries, where it’s a mish-mash of old and new customers. The models work extraordinarily well in an industry like this.”

And while the music industry is perhaps the most vivid example of an industry loathe to change its business practices, Fader says it’s simply a one of many “creative” businesses, from baseball to book publishing, that have typically relied on instinct over quantitative analysis when making strategic decisions. “These are very general issues,” he says. “The music industry just happens to be an extreme example. Too many industries really think their patterns are different and that they can’t learn from other businesses. They need to swallow their pride, drop traditional ways of evaluating success, and embrace the right kids of quantitative metrics with no hesitation. It’s important to realize just how astonishingly consistent the buying patterns are across industries. People are people. When you focus on the behavioral data as opposed to the surface-level details of a product, it doesn’t really matter what product it is.”

Crunch, Crunch

Collecting dollar bills with interesting serial numbers was Pete Fader’s favorite thing to do as a young boy. Groups of numbers were beautiful and mysterious to Fader, and his parents, both “world-class bridge players,” saw no harm in their son’s unusual preoccupation. “Every day when my mother would come home from shopping she would show me all of the interesting bills that she’d gotten that day. She actively encouraged that kind of thing not so much as an academic exercise but because I was into it,” says Fader, 42, a New York native. (Today he proudly owns the domain name www.coolnumbers.com, where he set up algorithms to help people check out the “interestingness” of their own dollar bills.)

Later, his passion for numbers turned into an obsession for baseball, with Fader compulsively gathering and analyzing tiny numeric details, from batting averages to box scores, throughout his teen years and into college. He was forced to pause during the 1981 players’ strike and realized that he had free time to seek other kinds of numbers to play with. Fader’s fixation for baseball waned, but his love of number crunching remained, straying to data sources such as the Billboard music charts. “It was a very nerdy life, and still is,” he says. “But now it’s directed at issues that people care about.”

Fader might have landed on Wall Street but for his “fairy godmother,” an MIT professor named Leigh McAlister (now at the University of Texas) who persuaded the math and business undergraduate to give marketing a try, despite his prejudice that the field was “soft, fluffy stuff.” “She showed me that marketing is actually a lot like finance, with lots of numbers, but the difference is that for me it was more fun to study TV advertising and retail shopping habits than stocks and bonds.” McAlister convinced Fader to stay at MIT for his PhD, something he felt was “great – another opportunity to play with numbers and not have to deal with the mundane responsibilities of a real-world job.”

He had no intention of, and even an active resistance to, becoming a professor. “The whole publish or perish, scholarly stereotype of tweed jackets with elbow patches – that wasn’t me,” he says. “I stayed in the program because it was fun, but I didn’t do the kinds of things that an ambitious PhD student should do. I didn’t take many courses. I didn’t network with other PhD students. I wasn’t interested in knowing lots of people in the field, because I didn’t think it would ever matter to me.” Fader’s indifference, combined with his now well-known self-deprecating sense of humor, seemed to endear him to his professors, who saw a spunky young man with raw talent and no ulterior motives.

When it came time to get a faculty position, Fader very nearly went to the Harvard Business School. But McAlister stepped in again, literally calling Fader’s friends and family in an effort to push him, instead, to Wharton. “She basically forced me to go to Wharton because she thought, correctly so, that this was the right place to go for someone with high research potential. I still call her up at least once a year just to thank her again and again.”

Even then, in 1987 as a new assistant professor, Fader was far from committed to academia. Slowly but surely, he found himself working on a range of research projects with marketing department colleagues. Before he knew it, he says, he had a tenure case. “I’m starting to come to the realization now, 17 years later, that I might be doing this for my career,” he says. “I have to honestly say, though, that for most of my years here I would walk around the halls smiling to myself knowing that I was an imposter, and that one day they were going to blow the whistle and kick me out of here. And that feeling was a great thing, because I didn’t have the same pressure that most people felt, and I was able to enjoy the ride. I was like a kid hanging around the New York Yankees locker room.”

“I’ve enjoyed a charmed life,” Fader says. “I tell this story because many undergraduate students have the same misperceptions of the academic career that I had. I’m always looking for students who have the talent but not necessarily the ambition. It’s just one way of paying back the favor that others have done for me.”

In addition to his ongoing work on the music industry, Fader is considering creating a new Wharton center that would focus on the media and entertainment industry, particularly through curriculum development, alumni networking, and job placement. The goal, he says, is to create a higher profile for Wharton as a leading school for media and entertainment business education — “the kind of training that future change agents in the industry will really need.”

In his teaching, Fader emphasizes the quantitative. He recently created a new course on probability models in marketing that he says is “big, ugly math right from day-one. There are no case studies, no group projects, and no touchy-feely stuff. It’s a pure skills course, and there’s nothing like it taught anywhere else.”

From this love of the quantitative side of marketing has come a “little army of disciples,” Wharton alums who, Fader hopes, will “march in to certain industries and take them over. There is a bit of a personal agenda there, but it really is for the good of industries that aren’t taking advantage of the data or human capital that they have,” he says. “This takes time, but it’s the only way to break out of the doldrums they are facing today. I do believe that 20 years from now, all of these so-called ‘creative’ businesses will be run much more effectively, as opposed to little medieval fiefdoms that they are today. It’s going to be a long, painful process getting there, but I’m committed to doing whatever it takes.”