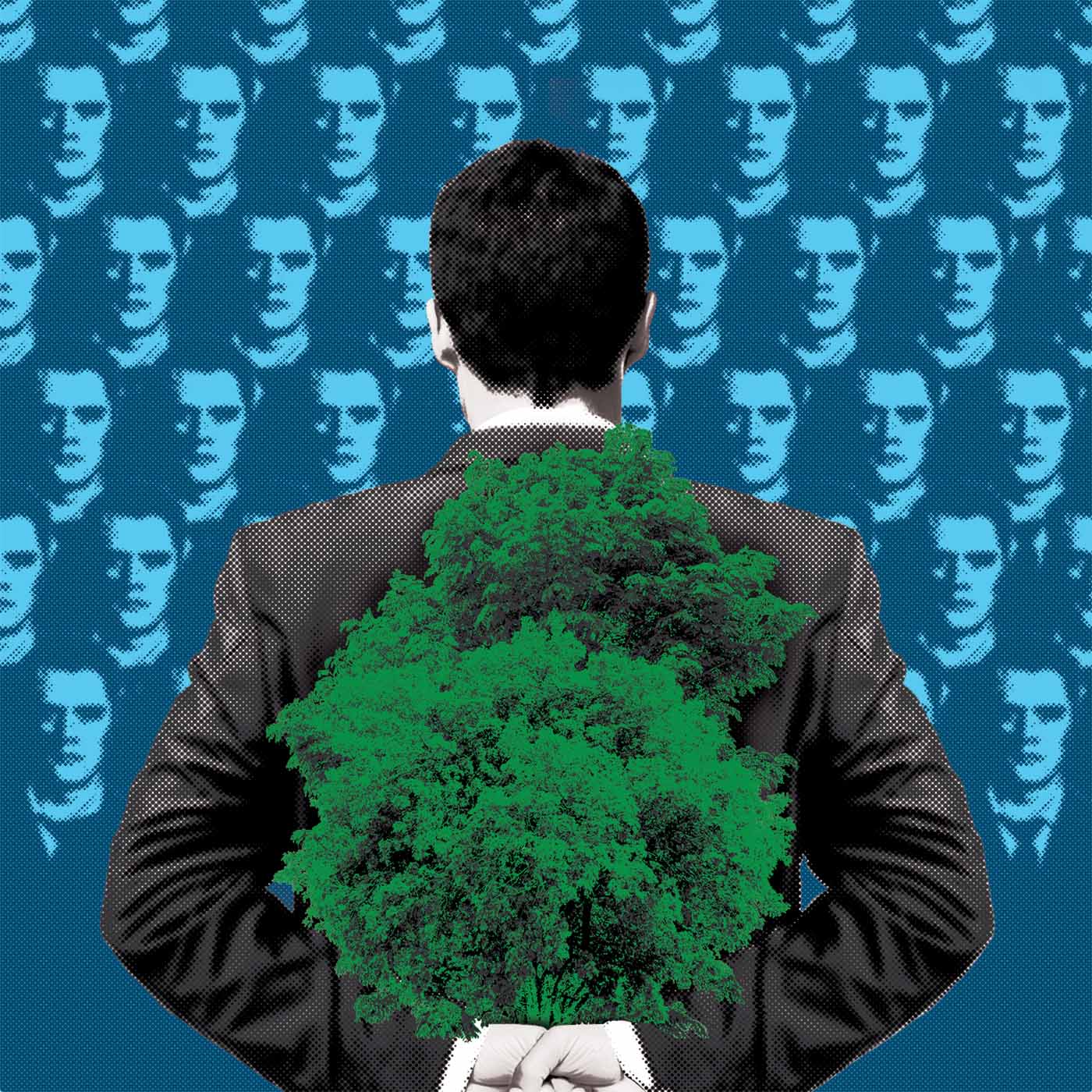

First, there was greenwashing — a term referring to deceptive marketing campaigns and other performative gestures by companies to make consumers and investors believe they’re environmentally responsible. Now, there’s greenhushing. And it’s also a problem.

Firms engage in greenhushing when they actively work to reduce their carbon footprints, produce less waste, manufacture less plastic, and build greater sustainability — but don’t tell anyone about their efforts. In today’s highly charged political and social climate, firms have valid reasons for keeping quiet, according to Wharton associate accounting professor Mirko Heinle.

If a company specifically states its ESG goals and reports its progress on those targets, it could face pushback from stakeholders who find the plans aren’t ambitious enough, Heinle said in an interview with Wharton Business Daily on SiriusXM. On the other hand, it could also face backlash from investors and politicians who believe ESG efforts undermine profits or run counter to prevailing values. “We can see how firms are maybe caught in the trap between appearing not green enough or too green,” said the professor, who teaches a course called Climate and Financial Markets.

Heinle cited an October report by South Pole, a global carbon finance consultancy, that found one in four companies is “going green, then going dark” by not disclosing its sustainability work. “Doing so makes corporate climate targets harder to scrutinize and limits knowledge-sharing on decarbonization, potentially leading to less ambitious targets being set and missed opportunities for industries to collaborate,” South Pole states. Heinle said that sentence makes clear the dilemma faced by firms despite their fiduciary responsibility to be transparent to shareholders. “It’s hard when you need to make a trade-off between financial performance and, for example, greenhouse gas emissions,” he said. “I can see how it’s hard to tell the world what exactly you’re doing — to know that you cannot satisfy both sides. You cannot maximize cash flows and at the same time minimize greenhouse gas emissions in a short time frame.”

One of the biggest challenges for firms seeking to improve their environmental, social, and corporate governance is a lack of standards across those dimensions. Globally, there’s no single method of data collection or measurement, which often leads to confusion and greater incentive not to share information. “Standardization could go a long way in helping here,” Heinle said. “What companies fear, in part, is standing out from the crowd. You’re the one who is reporting something, then you’re the one who is being scrutinized. When you and all of your competitors have to disclose the same thing, it’s likely that it’s not that different from each other.”

Yet the professor isn’t pessimistic about the future. Heinle said he believes that everyone — including firms — bears responsibility for blunting the effects of climate change. “I would say the bigger worry is not that firms greenwash, and it’s not that firms greenhush. The bigger worry is that nobody cares,” he said. “When people care, we should expect change.”

Published as “Why Some Firms Keep Quiet About ESG” in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Wharton Magazine.