A “bomb cyclone” of sub-freezing temperatures and 40-mile-per-hour winds is hitting Philadelphia in January, but Michael Platt GR94 walks into Huntsman Hall looking composed and comfortable in a black Patagonia coat, black turtleneck, ash black jeans and big brown boots. His beard and graying hair are trimmed tight, and his general demeanor is far more relaxed—chill, even—than that of anyone else pushing through the doors on Locust Walk and into the Sirius XM Wharton Business Radio studio.

Career Talk host and Executive MBA Director of Career Management Dawn Graham greets him: “I’m so happy to have you on-air.” While Platt considers himself to be—quite genuinely—no big deal, the enthusiasm surrounding his work is undeniable. Over the past decade or so, he’s emerged as a leading thinker and experimentalist in the fields of neuroeconomics and decision making. He is also perhaps the most intriguing faculty hire Wharton could have made.

Platt joined the University in July 2015 as a Penn Integrates Knowledge professor, with appointments in the Perelman School of Medicine’s Neuroscience Department, the School of Arts and Sciences’ Psychology Department, and Wharton’s Marketing Department, where he also serves as the founding faculty director of the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative (or, as it’s been creatively abbreviated by Platt and his staff, WiN). His bulging portfolio crosses multiple disciplines and ends in a series of say wha? questions: What exactly is the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative? And what fever dream resulted in this unlikely marriage of business and neuroscience?

On Graham’s show, Platt offers some insight. “We are primed by evolution,” he says, “to seek things that in the non-modern-day environment would have been very important for our success.”

The upshot, he continues, is that numerous items once scarce and vital—sugar and fat, for instance—are now easy to obtain and ubiquitous. Our brains, however, are still wired to treat exposure to fatty proteins—in the form of cheeseburgers or chocolate cake—like the discovery of water in the desert. With some beef in your belly, your brain deals out a flood of chemicals, like dopamine, that stimulate feelings of comfort, reward, and happiness. As a result, we crave new hits of such foods and risk growing fat. The trick, Platt suggests, is to replace these “habit-forming” rewards with healthier practices, like exercise.

“So, bottom line is the brain is working against us!” concludes Graham.

“That’s interesting phrasing you used,” Platt says. “‘Working against us’—the brain is us.”

The brief exchange set the stage for the range of topics in their ensuing conversation—from quitting smoking to finding your most fulfilling career path—and also for Platt’s new role at Wharton. His appointment here is novel, even revolutionary, but it’s also entirely evolutionary. Neuroscience, after all, relates to absolutely everything humans do, from putting on our pants to conceiving of new technologies and bringing them to market. Platt has been eyeing a synthesis of brain science and business for a long time, a marriage that will—if he’s right—change how corporations do just about everything, from marketing strategies to internal decision making and employee management. And in leading the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative, Platt looms as one of the world’s most important neuroscientists and the foremost explorer of the next frontier in business: the tangled mass of billions of neurons and synaptic connections that lies at the foundation of all human enterprise.

On a crisp morning after the Business Radio interview, Michael Platt peers over the shoulder of post-doc fellow Arjun Ramakrishnan, a technologist and researcher who is using a computer to slowly guide small sensors, painlessly, into the brain of a living monkey.

The brain is insensate, so the rhesus macaque looks at ease. Platt and Ramakrishnan are working in one of Platt’s labs, in the Smilow building on Civic Center Boulevard. On a small monitor, we watch the macaque use its eyes to engage in a foraging exercise on a TV screen just a couple of feet away. An eye-tracking device records the monkey’s every glance at a pair of blue, bush-like avatars that continually disappear and reappear at opposite sides of the screen. When the monkey looks at a bush, a machine in the control room dispenses a few drops of juice.

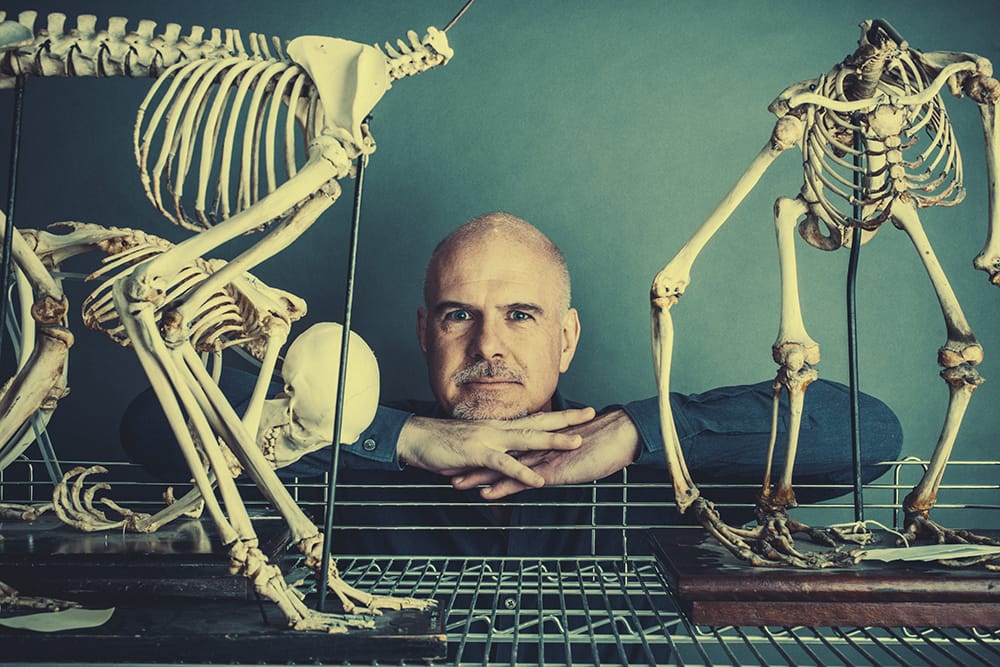

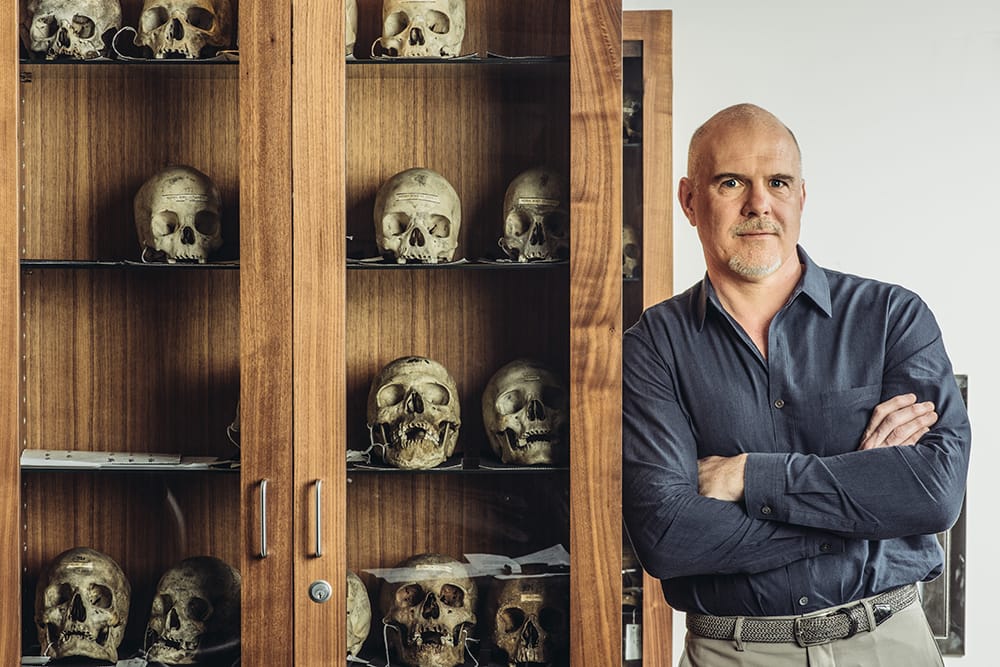

Gray Matters: Platt with some of the more than 1,500 skulls in the Penn Museum’s Samuel George Morton Cranial Collection.

What this has to do with business isn’t immediately apparent, but in fact, this experiment—like every Michael Platt production—cuts across numerous disciplines. Platt’s publications list, a scroll some 90 papers long, bears implications for anthropology, human psychology, economics, neuroscience, pharmacology, medicine, and primatology. Extrapolating such findings to business isn’t exactly easy—you gotta know how—but the applications are there. And plowing these fields has earned Platt global media coverage, from the Wall Street Journal to the BBC.

With a little hindsight, it’s apparent this unlikely life was Platt’s destiny. Born in 1967, he grew up in a Catholic family in a suburb just outside Cleveland. His dad was a mechanic, and his mom drove a school bus. Perhaps he would have embarked on a blue-collar career, too, but when he was around six years old, his grandfather gave him a gift. “It was a Time-Life book,” remembers Platt, “on evolution. I kept it in my bedroom all the way through high school.”

Before he could read, he’d turn the pages and marvel at the pictures of monkeys morphing slowly into men. Over time, he changed, too, as he understood the science involved. “I’m sorry,” he told his mother when he turned 13, the traditional age for Catholic kids to commit to the faith. “I just can’t do it.”

The northeast Ohio kid had two passions: science and football. He starred as a student and linebacker but gave up the gridiron as a freshman at Yale to focus on his studies. He earned his first degree in biological anthropology, then matriculated as a doctoral student at Penn, where he first conducted serious research into the foraging habits of monkeys. He found monitoring monkey behavior limiting, though; he couldn’t help wondering what was going on in their minds.

His old Penn mentor, psychology professor Robert Seyfarth, admits he “gulped” when Platt told him he wanted to branch out into neuroscience—“There is a lot of work necessary to make a move like that happen,” he told Platt at the time—but supported him. “Today,” Seyfarth says, “Michael is really unique—one of the only scientists doing the kind of work he does, that brings together the findings in so many fields and advances them with novel experiments.”

Platt was driven by a key insight: “If you look at who we are, what we evolved to do is very different than the lives we lead today.” The human brain, he explains, adapted to help us survive in cooperative tribes of perhaps 100 people—to find food, secure a mate, avoid danger. Modern life means navigating thousands of meetings in a global economy and drowning in information. In 40 years, we jumped from selling encyclopedia sets door-to-door to holding humankind’s accumulated wisdom in our pocket phones. The pace of change is so fast that our brains can’t evolve to catch up.

“This brings with it a lot of challenges,” Platt says. “How do we use this software, this hardware, which evolved for such a different set of circumstances, to live healthy, meaningful, happy lives now?”

This is the fundamental question, says Platt, facing us all. Securing the answer will build better people and better businesses, too.

At the start of spring semester, Michael Platt led a class of marketing students through what he characterizes as one of his driest lectures—a summary of technologies neuroscientists use to track brain activity in animals and humans (PET scans, SPECT imaging, patch clamps, fMRI, and more). Platt knows how to hold a room. At 50, he’s fit and trim, and his eyes hold a perpetual spark of childlike delight in almost every social interaction. His students listened as he spoke, attentive but reserved, even skeptical—budding acolytes still waiting to see the light.

Wharton is betting big on Platt to gain adherents. The business school’s investment includes the addition of Platt and his longtime administrative partner, WiN executive director Elizabeth “Zab” Johnson, a neuroscientist herself. Their growing empire sprawls across five offices and three separate labs; they’ve added 26 affiliate faculty members and offer two courses for undergrad and graduate students with a third coming next spring (an additional half dozen or so classes at each level are offered by other divisions of Wharton that also fit with the brain science mission). This April marks their first Executive Education course, “Leveraging Neuroscience for Business Impact,” and a new MBA program to award some sort of neuroscience-for-business degree is in the works.

In The Lab: Platt with postdoctoral fellows Annamarie Huttunen, Yaoguang Jiang, and Arjun Ramakrishnan inside a radio frequency-shielded experimental neuroscience room.

Platt had something of a blank canvas on which to draw the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative’s ultimate shape. His choices were, to some degree, determined by his own wiring: “It is in my nature,” he says, “to go big.” In short, the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative aims to reframe how businesses approach a wide variety of challenges—from attracting customers and getting them to buy, a traditional concern of marketing, to human resource functions like hiring and placing employees. For instance, he’s teaching executive education courses in which he provides “nano tools”—exercises that yield positive changes in the ways our brains are wired. Taking a walk outdoors reduces stress and activates parts of the brain responsible for creative thinking. Another exercise requires the executive to consider as many uses as possible for a pencil, other than writing. Thinking of this (or any other object) afresh activates a widespread neural network in the brain, which responds to increased activity much as a muscle does, by getting “stronger”—thus rendering said exec more creative, at least in theory.

Platt also aims to create comfortable, noninvasive means of gathering brain function data from subjects working in normal office environments. Rather than guide electrodes into our brains, he has a team working on headsets that look and feel pretty much like old-school headphones, the big ones that fit over the whole ear. The three-person team includes an engineer, a bioengineer, and Ramakrishnan. For now, the team’s name is Naanoscope—a play on the word “nano” and a nod to Ramakrishnan’s love of the Indian bread naan.

The Wharton Neuroscience Initiative is still so new, however, that to understand what it might accomplish, we have to look at Platt’s past. He began his grand “mash-up” of neuroscience and business at NYU, where he touched upon the same topic he addressed on Graham’s Sirius show—the reward systems encoded in the brain from humanity’s earliest days and how those ancient codes affect our decision-making. His papers helped establish the field of neuro-economics. But he cemented his reputation later, during an appointment at Duke, where he became director of the Institute for Brain Sciences and the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience. He also published an article that cemented his own reputation, on the “monkey porn” experiment.

Platt demonstrated that monkeys would willingly trade a valuable commodity—sweet fruit juice—for the opportunity to view images of other monkeys’ butts. It’s another great say wha? moment in Platt’s career, but there was tremendous wisdom in the experiment’s purpose and design. As animals that mostly shamble about on all fours or in stooped postures, monkeys advertise a lot about their vitality and health through their backsides. Healthier baboons, for instance, have bigger, redder rear ends and are more attractive as mates. Since we share a common ancestor with monkeys and evolved to thrive in similar intensely social groups, it seems reasonable that encountering particular features triggers some associated reward system in our neuro-circuitry—which could explain everything from women’s makeup to our species’ interests in sexy models and celebrity. There are medical implications to all this, including developing new treatments for impairments in social reward. But the application of such research in a business setting also bears broad significance.

Just how many personnel decisions are based on primitive, hardwired brain processes rather than performance? Charisma and attractiveness probably do matter in a boss—the “I’d follow her anywhere” theory of leadership. But are companies promoting people for talent, or for physiques, rosy cheeks, and facial symmetry? Clearly, this is information any CEO would like to know.

Platt has since continued to work in a similar vein, leveraging intimate looks at monkey neurology to develop new lines of research into human beings. One recent paper has a not-exactly catchy title: “Posterior Cingulate Neurons Dynamically Signal Decisions to Disengage During Foraging.” But determining which areas of the brain are responsible for the decision either to stay put or to instead explore, seeking food in new territories, provides new understanding of how human brains form similar decisions. What might entice consumers to discontinue “foraging” in one area of a store and move to another, or to click from one website to the next? How might ideal teams be constructed for given tasks? How many foragers and how many explorers should be assigned to particular projects? These same brain structures are likely determinative of who will be a big-picture CEO—visionary and exploration-ready (the next Steve Jobs, perhaps?)—and who would prefer to work out the details.

“We are exploring all of these questions,” says Platt, “with the idea of helping companies build better businesses and helping employees to maximize their own talents and interests.”

Exactly how fast this will all progress is difficult to work out. Some of Platt’s initiatives—the headgear he’s developing, for instance—might generate some announcements as early as this summer. He’s also using “eye tracking goggles”—think futuristic-looking eyeglasses—that can monitor the user’s eye movements in real time, outside laboratory conditions, to better understand what visual information is truly important to people before they reach a decision.

Other pursuits, like generating employee assessments that utilize this “forager/explorer” data as a starting point, will require various expansions and refinements for many years, even decades, going forward. But the ideas are already evocative—suggesting that a sci-fi version of reality is steaming toward us, a world in which basic neuroscience will ground best practices.

Seeing Things Differently: Platt wears eye-tracking goggles and a wireless EEG among the food trucks on campus. (Photograph by Kevin Monko)

Tori Westerhoff WG18 is among the first students to attend Wharton specifically because of the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative. “Seeing Michael Platt get hired,” she says, “made the decision to come here a lot easier.” With her cognitive-science degree from Yale, she can understand the circumspect expressions on the faces of the marketing students in Platt’s class. “When I tell other students why I’m here, I get quizzical looks,” she says. “And I understand. Not a lot of people come to business school to think about neuroscience, but when I get a chance to explain it to people, they seem to get it: Businesses are run by people, and people run on brains.”

Westerhoff conceives of a future in which some degree of neurological testing, including donning a wearable headset, could be part of the hiring or ongoing employee assessment process, though Platt puts the event horizon for such developments at perhaps 10 years. “I know that thought could be scary for a lot of people,” Westerhoff says. “It’s very sci-fi, but it’s also very real.”

At the end of his marketing lecture, Platt showed his students what he called a “primitive” application that spoke to this new reality. He narrated as Arjun Ramakrishnan donned a prototype of one of those wearable headsets, which monitored his brain function. Ramakrishnan, Platt explained, would transmit electrical impulses from his own brain, wirelessly, to a stimulator connected to a set of electrodes on a student volunteer’s arm. With just a thought, Ramakrishnan caused her to clench her fist. She shouted and laughed, her face a mixture of shock and joy.

“This is a crude demonstration of some of the technology under development,” explained Platt, “but it gives you the idea.”

Did it ever. Every time the woman’s hand jumped, she and the class whooped, the marketing students skeptical no longer, neuroscience the next frontier.

The morning was still young, as Wharton goes, and Michael Platt greeted an audience in a conference room on the eighth floor of Huntsman Hall with some observations that were both sobering and electrifying. “We are involved in the study of what it means to be human,” he said, and cited Minority Report, a work by one of his favorite authors, Philip K. Dick, that ruminates on how people will cope with dramatic technological advances. In that book and the movie based on it, people use brain-augmenting technology to predict specific homicides, preventing murders before they happen. “That seems so sci-fi,” Platt said, “but today, with a group of 24 undergrads, we can predict with neurological experiments how specific products will do in the marketplace. Is that really so different?”

What emerged over the course of the day during the summit on “The Ethical, Legal, and Societal Implications for Neuroscience and Business”—an annual event with a new point of focus each year—was a deeply nuanced view of the world Platt is envisioning. Such gear would give employers an unprecedented level of information about their employees, sparking talk at the symposium about privacy concerns. But if those concerns could be overcome—perhaps it would be legal to garner only a very specific subset of data?—those employees might also wind up a lot happier, assigned to duties, placed on teams, and hired into companies that are suited to their personalities.

At one point during the ethics summit, Josh Duyan C05, chief strategy officer at CTRL-Labs, showed a video that drew gasps from the crowd. In the clip, a technologist working on a new brain/computer interface played Asteroids on his phone. No big deal, except for the fact that this guy wasn’t touching the phone. A computer interface read his intentions in his mind, quickly enough for him to think “thrust” and escape from a massive oncoming rock.

Following up, Platt asked the crowd of perhaps 100 people for questions. Initially, no one raised a hand. “Somebody must have a question,” he deadpanned. “Or you’re just deeply, deeply troubled.”

The joke drew a laugh and underscored the moment. We stand at a dramatic precipice, with possibilities in the void ahead that are frightening and exhilarating. “I don’t want to downplay it,” says Platt. “These new technologies can seem scary and invasive. Could these things be used to manipulate people? Absolutely. But there is no putting the genie back in the bottle, and the best thing we can do now is formulate the questions. How are we going to develop the uses of this technology while being respectful of issues like autonomy and privacy?”

In Platt’s vision, there is no sense, or accuracy, in thinking of the future in singularly dystopian or utopian terms; with effort and care, he and WiN can make human life better.

During my time with him, Platt notes some early positive outcomes. Psychiatrist Gabriel Dichter at the University of North Carolina has used the “monkey porn” paper to fuel some of his research into autism. The “primitive” exercise Platt conducted in class by making a student’s hand jump could one day translate into wearable exoskeletons that would allow people with spinal injuries to walk via a neural interface that will recognize their thoughts. One of the world’s most innovative neuroscientists has come to Wharton with revolution in mind—to build better businesses and improve the human condition. Change is coming, Platt says, but we have an opportunity to shape those changes, minimizing the harms and maximizing the benefits. “There is a lot of good that can come from this,” he insists, “and that should be the focus. This isn’t about just getting people to mash the ‘buy’ button harder.”

Steve Volk is a writer at large for Philadelphia Magazine and a contributing editor for Discover.

Published as “’How To Examine Posterior Cingulate Neurons And Influence People” in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of Wharton Magazine.