What’s in a word? Consider the last email you sent. How many “I” words (I, me, my, mine) did you use? How many “we” words (we, us, ours)? Count your pronouns, your articles, your prepositions. What if I told you that within the text of that email you dashed off in the few minutes before lunchtime exists information about your social status, your emotional state, your gender, even whether you’re being deceitful or telling the truth—and all of it possible to decode through the simple act of tallying different types of words?

This is the power of text analysis, a burgeoning discipline in which researchers mine language for information to make sense of and even predict human behavior. On Friday, January 12, leading social science scholars from as far away as London Business School packed into a Huntsman Hall lecture room to attend the first annual Behavioral Insights in Text Conference, an all-day interdisciplinary event for researchers interested in using textual analysis and natural language processing to extract behavioral insight from textual data. The event was hosted by the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center in conjunction with the Technology and Behavioral Science Initiative, a program which seeks to use advanced computational tools to deepen the understanding of technology’s behavioral impact.

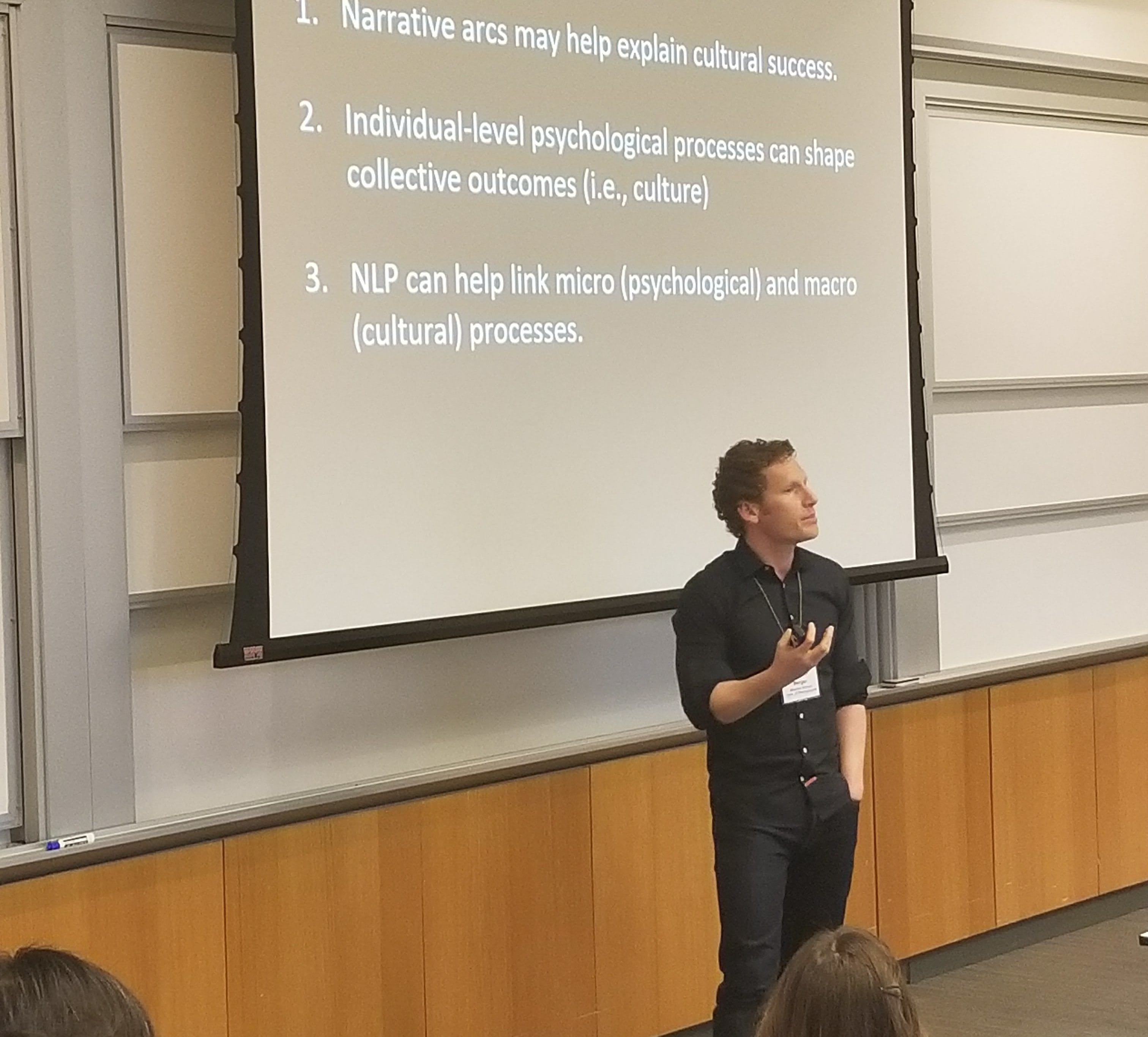

The conference consisted of four sessions, each divided into four 30-minute lectures in which researchers provided insights into how words influence our world, from the ways we generate ideas to our opinions and judgments. In her talk on gender bias in language, assistant professor of organizational behavior at London Business School Selin Kesebir demonstrated how our tendency to order social groups by relevance serves to reinforce harmful stereotypes; (think about it: When was the last time you said “female and male” versus “male and female”?). During the language and social media session, Wharton professor of operations, information, and decisions Kartik Hosanagar discussed findings that language which relates to brand personality tends to increase user engagement with Facebook advertisements. In his own presentation, Wharton associate marketing professor Jonah Berger—who organized the conference along with Robert Meyer, marketing professor and co-director of the Risk Management and Decision Processes Center—described how analyzing the emotional language within movies can predict how well they’ll be received.

Closing out the conference was Jamie Pennebaker, Regents Centennial Chair of Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, who ranks among the most cited researchers in the social sciences and helped establish the field of textual analysis with the creation of his Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software, or LIWC (pronounced “Luke”), a computer program that calculates the degree to which people use different categories of words across bodies of text.

“I would not be here today if it were not for Jamie and his work,” said Berger, a renowned social influence expert and the bestselling author of two books on consumer behavior. Early in his career, Berger conducted a study on why certain articles make the New York Times Most Emailed list—a study that later factored into his first bestseller, Contagious. After months of torturing research assistants with the task of coding thousands of articles according to a host of different dimensions by hand, a colleague introduced him to LIWC, which not only streamlined the research process, but opened Berger up to the world of language data processing. “I really owe Jamie a debt of gratitude.”

During his keynote address, Pennebaker stood in the basin of the tiered lecture hall, looking up and around at the diverse body of researchers who, like Berger, were all there, in some way, because of him. They were all pioneers, he explained, each of them laying the groundwork for a new way of thinking that will continue to evolve over time.

“We are at the beginning of the language world,” said Pennebaker. “None of us know what we’re doing. And I think that’s why it’s so exciting. Because we are the first people on earth to really be able to parse language like nobody else has.”