By Peter Conti-Brown

Art credit: Mark Bender

There is an old story, perhaps apocryphal, in which a newly appointed member of the Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve System was greeted by the Fed Chair with an apologetic explanation of the new governor’s status. The chair predicted that when the man introduced himself back home to his friends and family as a “governor of the Federal Reserve,” they were likely to think he was the administrator of the U.S. government’s unexplored Western forests.

There was a time when that story was funny. The Fed used to be an obscure, backwater government agency. The general public didn’t really know what the Fed was about—and probably didn’t much care. Even for those who paid attention to the economy, until roughly the early 1960s, the prevailing view was that the president and his administration were the first and last stop for economic policy.

Central banking was the hinterland; fiscal policy—the stuff of taxes and budgets and spending and deficits—the seat of power.

Bankers cared about the Fed’s obscure activities. The rest of the country wasn’t paying attention.

That story used to work. It doesn’t any more. Today, it’s not just bankers who are paying attention. Over the last 30 years—and especially since the global financial crisis of 2008—the Fed has become the target of an extraordinary proliferation of scrutiny, praise and condemnation.

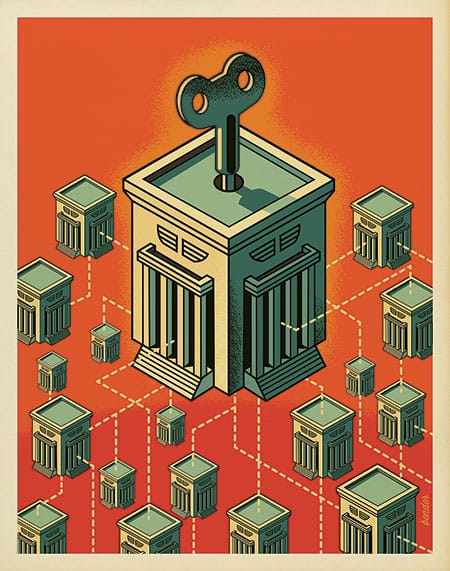

Today, it is not an exaggeration to say that in the popular imagination and in fact, the Federal Reserve sits atop the global financial system—and, indeed, the global economy—in a way that no institution has ever done before in our history.

“We are going through a period with no precedent in American history,” Alan Greenspan said in 2014 of the Fed’s brave new world. And he’s not the only one who has noticed.

But where public knowledge of the Fed’s existence has dramatically improved—people know the Federal Reserve deals with money, not forests—public knowledge of the Fed’s structure and functions has not. The problem is not one of public ignorance. The problem is that the Fed is one of the most organizationally complex entities in the federal government, with some of the most varied missions tucked inside.

How the Fed is structured, who pulls its many levers of power and to what end are cloaked in an opacity made darker through many generations of history.

Even the experts who study the Fed are left confused by the set of institutions that has survived.

A central part of that opaque mystique is the central bank’s curious location within government itself. Citizens do not interact with the Fed in the same way they do with other political institutions.

You don’t file your taxes with the Fed or receive your Social Security check from it. If you’re not a banker or an academic, you are unlikely ever to speak to a central banker at all. That distance can make it difficult to put the Fed, its policies and its power into our usual frames of discussion.

We are given a reason for this vaunted difference. The Fed is “above politics,” as President Barack Obama has said, protected by statute to remove the institution from the rough and tumble of our political process. It is, in a word, “independent,” according to the president.

That word: independent. It is everywhere in discussions of the Federal Reserve. But what does it actually mean?

Independent how? To what end? From whom? While we are asking questions, who or what do we even mean when we say “the Fed”? There are some stock answers to these questions. Normally, we say the Fed is represented by the Fed chair—Alan Greenspan or Ben Bernanke or, today, Janet Yellen—who enjoys legal separation from the political process so that she can make decisions to maintain the integrity of our nation’s currency in a way that focuses on technical expertise rather than ideology.

In my book, The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve, I argue that these usual answers are wrong.

First.

The Fed is a “they,” not the Fed chair, the Fed is organized as a series of interlocking committees that all participate in various ways to make Fed policy. Putting these many and varied internal actors in their context is crucial to understanding how this policymaking process occurs.

Second.

We cannot understand the structure without a close, historically sensitive reading of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, as it has been amended over the last 100 years. Too few people who study the central bank take on this task. an “it.” While we fixate on Federal Reserve System’s At the same time, the law is also not enough. Law in practice differs in sometimes surprising, contradictory ways from law in the books. Politics, personalities and relationships matter as much—sometimes more—than the statute.

Third.

Near-sighted presidents their electoral problems aren’t the only outsiders keen on influencing the Fed’s policies, even among politicians. Members of Congress, bankers, economists and others all influence the shape of the space within which the system operates. How and to what effect they succeed are essential questions for understanding the Federal Reserve. The Fed exists in a political world, and politics is an art practiced by many others beyond politicians.

Fourth.

The Fed’s policymakers 100 years, become much more than defenders against inflation. They are also, by statute and practice, recession fighters, bankers, regulators, bank supervisors and protectors of financial stability. A theory of independence that accounts for but one function (price stability) among so many others is not a very good theory.

Fifth.

These many missions technocrats wielding mathematical formulas. The Fed’s policymakers are people. They have ideologies, like all people. And the policies they formulate and implement require the exercise of value judgments under uncertainty, informed by their technical training, but not decided by formula.

The Fed that emerges from this more comprehensive and comprehensible anxious to inflate away have, over the last are not the bailiwick of picture is one that is much more modest than the Fed’s public image suggests. The central bankers that toil within the Fed—those whose names and faces appear in the newspaper and those who wield power more or less anonymously—cannot cure every ill, nor are they the cause of every crisis. But their authority over the financial system and the money supply is expansive. That power deserves a better public understanding. That independence deserves a better public engagement.

Peter Conti-Brown, assistant professor in the Legal Studies & Business Ethics Department, studies central banking, financial regulation and public finance, with a particular focus on the law, history, politics and economics of central banking at the U.S. Federal Reserve. This essay was adapted from his book, The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve, now available through Princeton University Press.