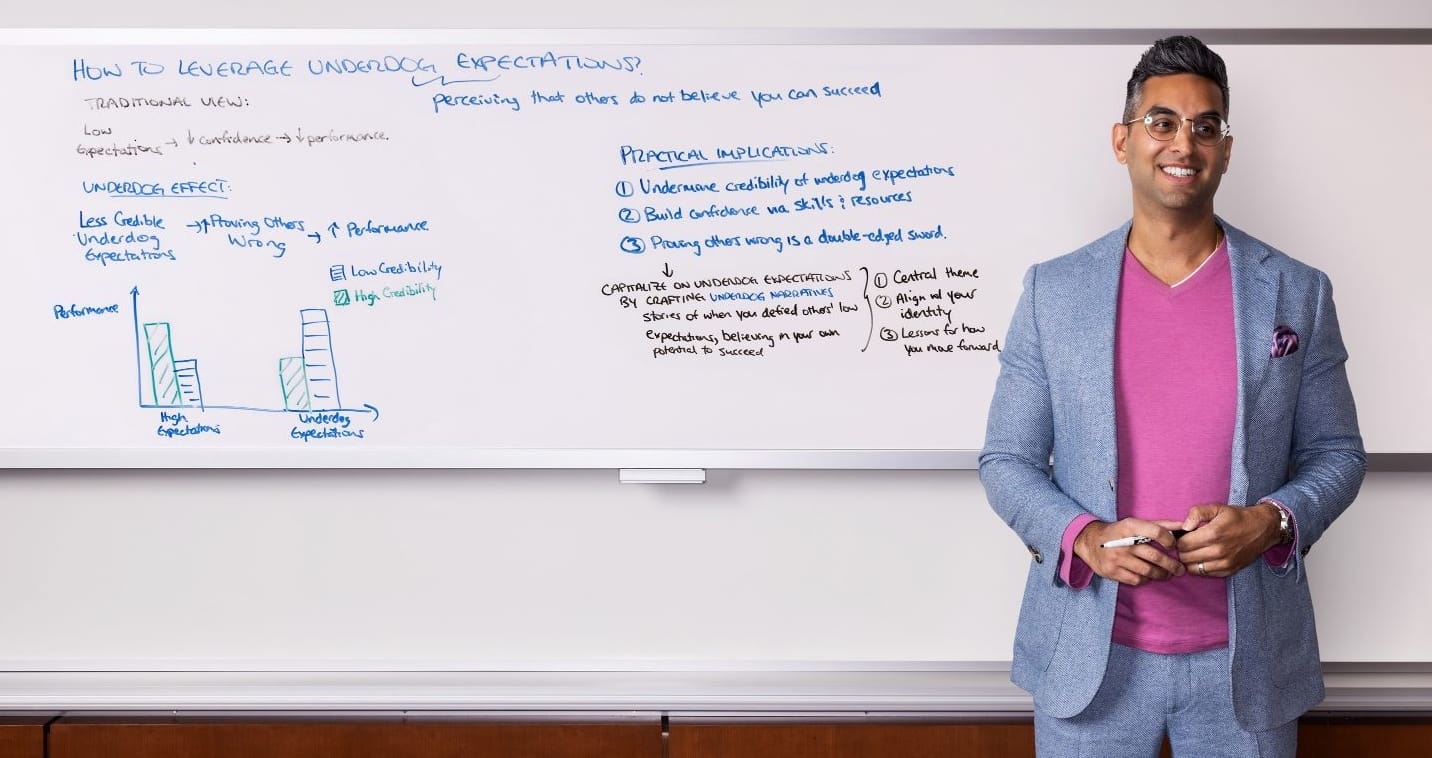

You may think that low expectations undermine confidence and hinder performance, but according to a new series of studies from Wharton assistant management professor Samir Nurmohamed, that’s not always the case. In this lecture from his Power and Politics in Organizations class, he argues that “underdog expectations” aren’t always detrimental. The need to prove others wrong, he says, can be a great motivator.

You may have heard that Michael Jordan was cut from his high school’s junior varsity basketball team; years later, as one of the greatest NBA players ever, Jordan himself is still telling that story. Even after achieving success, Microsoft and Apple wanted to be viewed as underdogs; Nurmohamed mentions how Bill Gates quipped that the day Microsoft stopped doing so, its competitors would eat its lunch. From David and Goliath to Truman vs. Dewey to the Miracle on Ice, underdog stories are embedded in our culture. “We live in a world where low expectations are all around us,” Nurmohamed says.

In a study examining the effects of prior discrimination on employment, Nurmohamed’s team had job seekers craft either a favorite narrative (a time when others were confident in them and they were confident in themselves) or an underdog narrative (a time when they defied others’ low expectations). The result? The ramifications of prior experiences of discrimination on finding employment were weaker for job seekers who crafted underdog narratives than those who developed favorite narratives. The underdog narratives were more beneficial for self-confidence.

Of course, when it comes to what others think of us, high expectations tend to be more helpful. But Nurmohamed also found that if you can undermine the credibility of someone’s underdog expectations for you — for example, by demonstrating skills they didn’t know you had or successfully challenging their expertise — it’s likely to lead to higher performance.

So how can managers best leverage the underdog effect? By striking a good balance and avoiding the “double-edged sword” of trying to prove others wrong. “You need to point to some successes or a path forward,” says Nurmohamed. “If low expectations are out there, don’t just ignore them, but point to them. Then you as a leader have to make the team feel like they can succeed.”

Published as “At the Whiteboard With Samir Nurmohamed” in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Wharton Magazine.