As the senior manager for global demand planning and inventory at Chicago-based Life Fitness, Dayna Bender WG99 was used to anticipating the intricate rhythms of the company’s business. But more than a year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the once-precise art of supply chain management had been transformed into a carousel of chaos. Life Fitness, which manufactures and sells exercise equipment to hotels and gyms, was hit hard by the pandemic’s fallout: Factories operated in fits and starts as infections surged, and shipping times for critical parts doubled (or worse) just as consumers were rushing to fill their burgeoning home gyms with workout gear. And now, Bender learned during a videoconference last spring, there was a new problem.

The powerful winds of a churning late-March sandstorm had knocked the Ever Given, a 1,300-foot container ship, sideways in the Suez Canal. From above, the vessel looked like an oversized Tetris piece that had landed askew. But the Ever Given — and its 18,000 shipping containers — was hopelessly stuck. And among its cargo was Life Fitness equipment that needed to be sold as soon as possible, since it was slated to be replaced by a newer model. Bender, told her company’s merchandise was part of an international incident that would ultimately take weeks to sort out, responded with a wry laugh and a shrug. “It was like, ‘What else can go wrong?’” she says.

The worldwide supply chain, so prized for its efficiency, struggled to withstand the critical disruptions the pandemic caused and to meet the consumer demands created by an almost-overnight reordering of everyday life. And the price of ongoing supply shortages was steeper than having to occasionally scavenge for toilet paper. According to a Biden administration press release, the global shortfall of semiconductor chips — essential to car engines, smart phones, televisions — subtracted a full percentage point from the U.S. gross domestic product in 2021. A report commissioned by GEP, a New Jersey-based supply chain strategy and software company, found that the ongoing disruptions caused a loss of up to $4 trillion in revenue among U.S. and European companies in 2020 alone.

The pandemic, and all its attendant heartache and headaches, has been endlessly trying, even as it has inspired new levels of resourcefulness and creativity. But the virus is just one wave in a sea of overlapping crises. Extreme weather patterns worsened by climate change and new military conflicts both pose significant threats to our collective ability to get things when we need them.

The pandemic, and all its attendant heartache and headaches, has been endlessly trying, even as it has inspired new levels of resourcefulness and creativity. But the virus is just one wave in a sea of overlapping crises. Extreme weather patterns worsened by climate change and new military conflicts both pose significant threats to our collective ability to get things when we need them.

“Supply chains are very, very long, with many different players,” says Wharton’s Gad Allon, the Jeffrey A. Keswin Professor and professor of operations, information, and decisions. “You might do everything right, and you still won’t have the products you need. But as a consumer, it’s hard to understand why shelves are empty. It’s very hard to blame a specific person, which makes it very hard to articulate.” Bender’s pandemic experience, with that of other Wharton alumni who live and breathe supply chain management, offers a frank look at the depth and complexity of some of the disruptions that have unfolded during the past few years and how we might gird ourselves for even greater challenges in the future.

The nation had trained its anxious eyes on California. It was early March 2020, and the Grand Princess, a cruise ship that held more than 2,400 passengers, was being forced to putter off the coast of San Francisco after nearly two dozen people on board tested positive for COVID-19. Simultaneously, the World Health Organization announced that the virus had been declared a pandemic, and California’s governor ordered the state’s 40 million residents to stay home as much as possible. At Oakland-based Kaiser Permanente, Robert Yeh ENG92 W92 realized that the health-care system was about to be overwhelmed.

“We were caught pretty unprepared when COVID-19 first hit,” says Yeh, Kaiser’s senior director for procurement and strategic sourcing. As the number of diagnosed cases ballooned into the millions nationwide, the nonprofit quickly discovered that it didn’t have enough personal protective equipment, ventilators, or respirators. “We were competing against pretty much everybody,” Yeh says, “including the federal government.”

Telemedicine replaced in-person visits for all but emergencies; on a practical level, that meant Yeh needed to find cameras and other equipment for the nonprofit’s 23,000 doctors and 65,000 nurses. “We didn’t have enough video cameras available. They were sold out everywhere, even on Amazon,” he says. “Network bandwidth was really low, because now everyone was working from home.” Kaiser was forced to get creative. It forged partnerships with retailers, including Staples and Gap, to meet its need for PPE and leased a new warehouse in California to build inventory and manage crucial supplies and equipment. “We’ve done a good job of preparing for the next wave,” Yeh says, “whenever the next wave is.”

Anatomy of a Global Breakdown

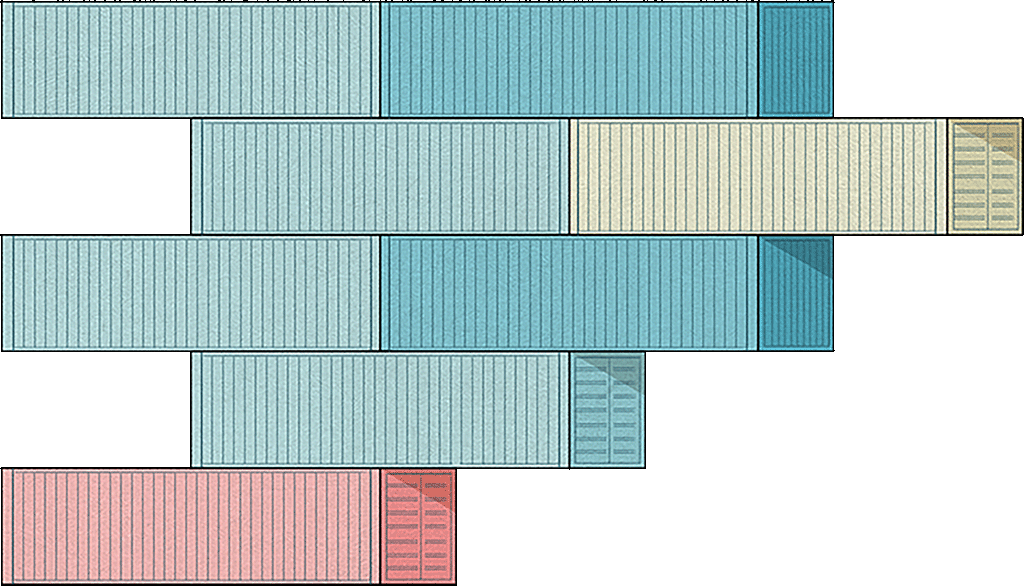

As the pandemic unfolded in 2020, Dayna Bender WG99 grappled with pandemic supply-chain disruptions across the world. 1. Bender’s company, Life Fitness, had time-sensitive cargo on the Ever Given, which got stuck in the Suez Canal. 2. COVID-19 outbreaks led to closures of factories in Vietnam, including those manufacturing microchips critical to her company’s equipment. 3. When the pandemic began in the spring of 2020, Bender learned China was closing its ports. 4. Attempts to avoid crowded Los Angeles ports by routing shipments through Vancouver were met with delays due to intense storms. 5. Shipments expected to arrive by train in Chicago — where rail yards closed that summer — were instead stuck in Mexico.

Two thousand miles from Yeh, Dayna Bender grappled with a different set of challenges during the pandemic’s early days. Manufacturing plants and ports were closed in China. Illinois implemented its own stay-at-home restrictions, shuttering the gyms and hotels that were Life Fitness’s core business. “We knew a supply shock was coming,” Bender says, “but at that point, we didn’t know there would be a demand shock.” It was unclear when it would be safe for Americans to return to their old routines, so many threw their checkbooks (and government stimulus money) at creating elaborate home everythings — offices, theaters, workout spaces. Life Fitness sold equipment directly to consumers, but it couldn’t replenish its inventory or meet the demand for simple items like dumbbells. “Everybody wanted dumbbells,” Bender explains. “Dumbbell manufacturers couldn’t make them fast enough. The demand signal became distorted. One person wants a set of dumbbells, so they look in 10 places. Now 10 retailers want dumbbells.”

Conventional wisdom held that the supply chain would prove to be resilient — that the gaps and delays would be short-lived once the world adapted to life during a pandemic. It was a comforting thought. But Life Fitness’s efforts to introduce new products were repeatedly stymied by forces beyond its control. Shipments that once took six weeks to arrive from Asia now took twice as long. COVID surges in Vietnam shut down a factory that produced the microchips Life Fitness needed for consoles on its treadmills and exercise bicycles. For a brief period, railroad giant Union Pacific stopped sending cargo trains from California to freight yards in Chicago due to a bottleneck of shipping containers. “It’s very hard to innovate in this environment,” Bender says. And then came the Suez Canal fiasco. It took six days for the Ever Given to be righted — and six weeks for the Egyptian government to release its cargo, says Bender. “Sometimes I think, ‘Why can’t we source more domestically and have shorter lead times?’” she says. “I’ve thought about that for years. But a lot of raw materials are still coming from somewhere else.”

The world has weathered severe fluctuations of supply and demand before. The Great Recession of the late aughts dramatically suppressed consumer demand, and the widespread destruction unleashed by the 2011 tsunami in Japan resulted in production shortages of new cars and semiconductor chips. But the pandemic introduced a wholly unique problem: a supply chain that couldn’t keep pace with soaring, and rapidly changing, consumer demands. Gad Allon is often asked if we’ll see a return to normal soon. His response is blunt: “Not even close.” It’s not an answer anyone wants to hear, but it rings true. “The term ‘normal’ is what’s confusing here,” he says. “It’s still not clear what the new normal is.”

The pandemic’s toll on the supply chain was illustrated most clearly in stark images that loomed large in the public’s imagination: bare shelves and long lines at supermarkets. Shipping containers piled precipitously high, like a child’s blocks, at ports. Lots filled with acres of unmovable cars. Left mostly unseen was the scrambling that played out behind closed doors as executives tried to figure out how to adapt to a crisis that had no modern precedent.

Michael Kress WG15 started a new role as the global vice president for logistics planning at Anheuser-Busch InBev in March 2020, just as the first round of social restrictions and shutdowns cascaded across the U.S. Bars, ballparks, and arenas — really, anywhere people had once drunk beers and felt something that resembled joy — went dark, with no clear timetable as to when they could safely host crowds again. “We had meetings with a daily focus on disruptions,” Kress says. “We were doing scenario planning I remember presenting to our CEO with a worst-case L-scenario where we’d lose a double-digit percent of our business.” Other large companies, including Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble, began delisting multimillion-dollar product lines. AB InBev braced for the worst.

Faced with 24/7 existential fears and cut off from normal social gatherings, Americans binged streaming content from their homes, massaged their groceries with disinfectant wipes — and stocked up on alcohol like never before. “All of a sudden,” Kress says, “beer sales went up dramatically. Everyone was grocery-shopping and buying in bulk.” While it was perhaps unsurprising that people found solace in their favorite adult beverages, the pandemic demand presented AB InBev with a logistical problem. The company had in recent years tracked a growing customer preference for cans over bottles. Now, that demand grew exponentially in the space of a few weeks. “The pandemic accelerated existing trends. It was like 10 years in one year,” Kress says. “We were short on cans and at the mercy of our suppliers’ availability.”

Marshall Fisher, the UPS Professor and a professor of operations, information, and decisions at Wharton, notes that years of supply chain optimization led many companies to rely on sole sourcing. “The biggest line of defense is dual sourcing, having two suppliers,” he says. The process of finding and qualifying a secondary supplier can be time-consuming and expensive. But Fisher recalls an anecdote about an electronics company that had factories in China and Mexico and shifted production between them at different points during the pandemic. “It’s a perfect example of fighting COVID with two points of supply,” he says. “Problems happen, but not everywhere all the time, at the same time.”

At AB InBev, Kress says, the pandemic pressure led to greater collaboration between different spheres of the company as it searched the world for new can suppliers. Other problems surfaced, however: absenteeism in factories; a shortage of truck drivers. When a 2021 winter storm in Texas crippled much of the state’s power grid and claimed at least 246 lives, a critical AB InBev manufacturing plant in Houston closed for a week. “There are very few quarterly reports that don’t talk about the supply chain now,” Kress says. “The CEO is speaking supply chain language. You can’t not talk about it anymore.”

Philadelphia-based Aramark Corp. found itself in a unique position during the pandemic’s first wave. Chip McIntyre WG00, a senior vice president of strategic sourcing, and Autumn Bayles WG00, a senior vice president of global supply chain, recall that the food services and facilities management company had a sudden glut of perishable inventory at a time when supermarkets had trouble obtaining paper products, cleaning supplies, and meat. “It was like a super case study on Supply Chain 101,” Bayles says. Aramark funneled some of its excess inventory to retailers and tried to keep pace with a nationwide need for school meals to be prepackaged and available for weekly pickups. “The decision making within the supply chain has sped up,” McIntyre says. “Things that may have taken two to three weeks to consider, because the supply chain was so efficient, now have to be decided in two or three hours.”

Philadelphia-based Aramark Corp. found itself in a unique position during the pandemic’s first wave. Chip McIntyre WG00, a senior vice president of strategic sourcing, and Autumn Bayles WG00, a senior vice president of global supply chain, recall that the food services and facilities management company had a sudden glut of perishable inventory at a time when supermarkets had trouble obtaining paper products, cleaning supplies, and meat. “It was like a super case study on Supply Chain 101,” Bayles says. Aramark funneled some of its excess inventory to retailers and tried to keep pace with a nationwide need for school meals to be prepackaged and available for weekly pickups. “The decision making within the supply chain has sped up,” McIntyre says. “Things that may have taken two to three weeks to consider, because the supply chain was so efficient, now have to be decided in two or three hours.”

Not all companies found an easy path to overcoming their supply chain shortages. For much of the pandemic’s first two years, Bibi Takou WG12 served as a director of strategy at Cummins Inc., an Indiana-based engine manufacturer. Some of the largest truck manufacturers in the country — Paccar, Navistar, Daimler — run on Cummins’s engines. Or at least, they did, before the now-infamous global shortage of semiconductor chips arose. Many automakers, fearing a steep recession in the pandemic’s early days, curtailed orders of microchips, which are an essential engine component. Those suppliers, in turn, found a more lucrative alternative, producing chips for pricey electronics — smartphones, computers, televisions, appliances — that Americans began upgrading with gusto.

As a result, thousands of cars and trucks sat idle on lots in the Midwest, a silent testament to the enormity of the supply chain breakdown. “There are so few of them,” Takou says of international microchip suppliers. “It’s not like you have a lot of parallel supply options. You are literally depending on one or two or three manufacturers.”

As gyms closed, customers searched for at-home exercise equipment. But the companies that make dumbbells couldn’t meet the demand.

Executives from General Motors and Ford predicted that microchip shortages would ease later this year. The optimism was badly needed; in 2021, the auto industry lost production on more than seven million cars and trucks, costing more than $200 billion in lost revenue. But some international chip suppliers insisted that the shortage would continue beyond 2022. Little wonder, then, that the Biden administration in January touted a plan for Intel to spend up to $100 billion to build what could become the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturing factory, in Ohio. A month later, the U.S. House passed the America COMPETES Act — providing $52 billion to boost domestic chip manufacturing — as part of a larger legislative effort to address supply chain woes.

“I think there will always be disruptions to the supply chain,” says Takou, who now works as a supply chain strategy director at Johnson & Johnson. “These natural disasters always happen, whether it’s a pandemic or some sort of environmental crisis or even a manmade crisis. What shocks people is how bad it can be.”

At some point in the not-too-distant future, COVID-19 will settle into an endemic state in which outbreaks no longer paralyze cities and countries for months at a stretch. But that doesn’t mean supply chain experts will finally be able to exhale. Climate change is worsening, and any number of manmade calamities — including military confrontations, like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February — will almost certainly cause more disruptions.

None of this is news to Dayna Bender. In November, Life Fitness attempted to circumvent the backlog at the Port of Los Angeles by routing a rail shipment of material through Vancouver on the way to a factory in Minnesota. It was a nimble move on the company’s part, but it, too, ended with Murphy’s Law frustration: A record-breaking storm dumped more than 10 inches of rain across British Columbia in just 24 hours, causing widespread flooding and $2 billion worth of damage. “The trains couldn’t run, and the parts were delayed,” Bender says. “When people say it’s too costly to address climate change, well, we had to pay the cost of those containers not coming in on time.”

Since 1980, the U.S. has recorded 310 weather disasters causing more than $1 billion apiece in damages. Twenty occurred last year alone, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Barley production in the U.S. fell in 2021 to the lowest levels in a century because of droughts in the Northwest and Midwest. “It’s important to remember that beer is an agricultural product,” Michael Kress says, adding that AB InBev made major investments in sustainability over the past decade aimed at reducing its carbon footprint and mitigating some of the effects of global warming on crop growth. “It’s not like we just realized recently that climate change will impact our business,” he says. “We have been working across our entire value chain to drive initiatives like smart agriculture and water stewardship to ensure our supply chain is prepared for a more volatile environment.”

Still, Allon worries that companies and policymakers will become complacent once the pandemic disruptions subside. “Climate change is a little bit like supply chain resiliency. It’s a topic people like to talk about, but no one likes to bear the cost now for a future that’s more stable,” he says. He argues that firms should commit to fully assessing the risks of their individual supply chains and build extensive mitigation plans. Some will explore dual sourcing or near-shoring, while governments might seek supply agreements with their allies. “But I’m not seeing many encouraging signs,” he says. “The reality is that most firms have a very short memory. In 2022, every CEO will have ‘supply chain’ as a top three concern. In 2023, it’ll long be forgotten.”

Of the 400 U.S. and European executives who participated in a GEP study titled “Cost of Supply Chain Disruption,” a majority said that supply chain resiliency and redundancy are now more important than efficiency and predicted companies would make significant changes within the next five years to maintain their supply chains. “Before, our job always was to optimize and make things more efficient,” says Chip McIntyre. “We could say, ‘How do we get another percent out of this part of the supply chain?’ You would work on that and think it through. Now, it’s like, okay, we need supply assurance. How do we make sure we actually have supply coming?”

Of the 400 U.S. and European executives who participated in a GEP study titled “Cost of Supply Chain Disruption,” a majority said that supply chain resiliency and redundancy are now more important than efficiency and predicted companies would make significant changes within the next five years to maintain their supply chains. “Before, our job always was to optimize and make things more efficient,” says Chip McIntyre. “We could say, ‘How do we get another percent out of this part of the supply chain?’ You would work on that and think it through. Now, it’s like, okay, we need supply assurance. How do we make sure we actually have supply coming?”

Fisher suggests that companies explore having a month’s worth of extra inventory as one hedge against future disruptions but notes that it’s difficult to accurately predict crises. As proof, he cites the devastatingly quick spread of the Omicron variant, which threatened to unravel several years’ worth of pandemic progress. “We tend to think of supply chain disruptions as major, cataclysmic things, like COVID or war,” he says. “But there’s always a steady drumbeat of things going wrong.”

The pandemic supply chain crisis, though, felt like a glimpse into a future no one wants to reckon with, a time when our instant-gratification economy — tap your thumb against your phone and have the product on your doorstep a day later — faces more permanent interruptions and shortfalls. One of the few comforts of pandemic life, after all, has been a general hope that our shared discomfort will be temporary — that we haven’t crossed a one-way bridge into a new and more challenging world. “You can put anything on paper,” Kress says. “But actually preparing for different scenarios is quite difficult.”

David Gambacorta is an investigative reporter at the Philadelphia Inquirer and a freelance writer.

Published as “What Else Can Go Wrong?” in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Wharton Magazine.