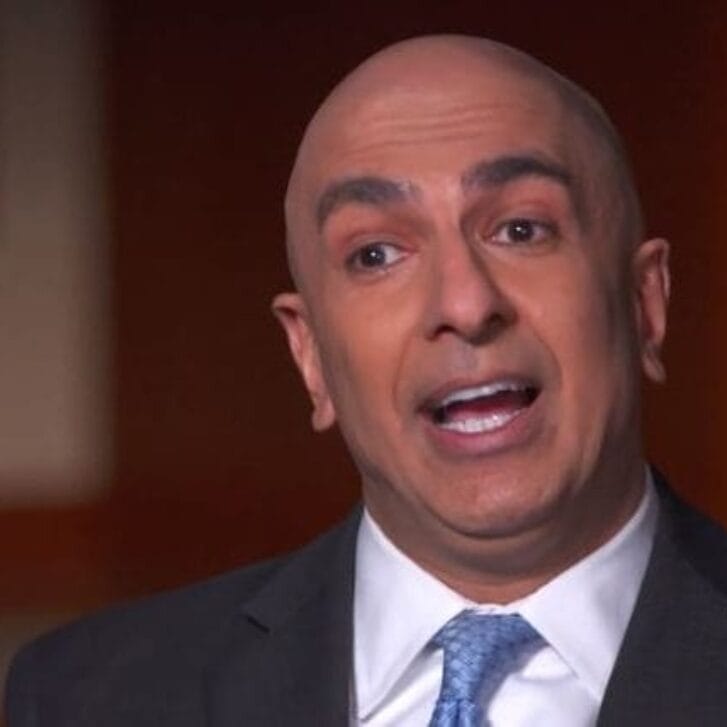

The nickname “the $700 billion man” has stuck with Neel Kashkari, WG’02, even after he left the U.S. Treasury Department for investment giant PIMCO. As the world crashed around them, Secretary Hank Paulson entrusted Neel to implement the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). He essentially launched a giant startup at Treasury, hiring about 140 people, completing 600 transactions and putting $400 billion into the financial system before he left in May 2009. Indeed, Neel co-authored the plan to loan Uncle Sam’s money to the banks. The program has netted the U.S. government $46 billion in profits as of last count, yet Neel was lambasted from across the political spectrum. Perhaps most impressively, he is considering public service again.

WHARTON MAGAZINE: Why did you go to Washington with Henry Paulson in 2006?

NEEL KASHKARI: Ever since I was a child, I had an interest in public policy. My first memories of it were watching Sunday morning Washington talk shows with my father when I was in elementary school. When President Bush selected Henry Paulson to become Treasury secretary, I called him up—I met him once, but I didn’t know him well—and I said, “I want to come with you. I don’t care what you want me to work on. I don’t care if you want me to lick envelopes. I just want to come and learn and serve and try to contribute.” I had been at Goldman for four years. Things were going great. A lot of people thought I was crazy. How could I give up a great career at Goldman to take some staff job at Treasury? And to me, this was a complete and utter no-brainer, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

WM: Why did Paulson let you come on board with him?

KASHKARI: I think he saw that my interest in public service was genuine. But he also made some calls and checked me out. The bet I was making was that I would be able to prove myself to him and become valuable to him, and become valuable to the department, and contribute over time. When I first got there, he gave me projects that were not core to his portfolio. And as I proved myself with those side projects, he gave me more and more responsibility, and ultimately, when the financial crisis hit, I became his go-to person for everything we did in response to the financial crisis.

WM: When that financial crisis did hit, what qualities do you think helped serve you best?

KASHKARI: The kind of pressure we were all put under… I watched people much older than me, much more experienced than me, frankly, shudder and break under the pressure, for lack of a better word. I learned that I was able to think clearly. And the more pressure that was put on us, the more I focused solely on what we could control.

WM: Do you think this ability is innate in you, or learned?

KASHKARI: I think it’s a combination of both. I think the strength and confidence to do what’s right, even though it may not be popular at the time, is something from within. But I also think strength and confidence you can learn from others. Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke were terrific role models because both … were laser-focused in doing what they believed was the right thing to do. They did not care about ideology.

WM: How will history view the response to the financial crisis?

KASHKARI: I think that history’s already being written. That it was unfortunate. None of us wanted to have to use taxpayer money to stabilize the economy. We wanted to let banks fail because they deserved to fail. But when a cascade of failures would have plunged the U.S. economy into a depression, when blue chip industrial companies weren’t going to be able to pay their employees, when ATMs wouldn’t have cash to give out, that’s when we knew we had to take bold action to intervene. So I think history’s going to show that this was a time of economic crisis for our country, but a time of absolute political courage. In some sense, it was almost our political system’s finest hour. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP ) was the best example we have in modern history of Republicans and Democrats coming together to do something controversial, absolutely necessary, the right thing to do, and in the end, highly effective.

WM: Why the move to PIMCO right after TARP?

KASHKARI: I wanted to go back to the private sector. I just looked for an opportunity to go back and to build something. Much of what I was doing in Washington was building, right? Building teams, building organizations, building our response to the economic crisis. I wanted to use some of those skills back in the private sector. And coming to PI MCO was a great way to do that because PIMCO was looking to build a new equity division, which I could help kick-start.

WM: And your move out of PIMCO potentially back into public service in California?

KASHKARI: Three things really happened. Number one, the November election happened. The Republican Party really did poorly nationally, but especially did very poorly in California. Number two, the Republican Party and especially the California Republican Party have so alienated minorities and immigrants and young people. And me being still young, I’m 39, the son of immigrants, I’m not the typical California Republican. Then third, importantly, the primary process in California has changed. And so when those things lined up for me, I said, “I need to take a hard look and see, is there a way for me to return to public service in California?” Because frankly, if a guy like me who has a passion for public service and is very high energy is not willing to try to help our state get better, on jobs, on education, then things aren’t going to get better.

WM: You’ve said your Treasury experience defined your life to date. How do you top it?

KASHKARI: It’s not about the role, honestly. I want to make a difference. And that could be in the government sector. That could be in the private sector. That could be in the nonprofit sector. My exploration is not about a fancy title. I had a very fancy title at PIMCO. I want to make a difference. And so I’m trying to find the best way I can do that.

Read about the four other Whartonites “Putting Knowledge Into Action.”