Need to get yourself over to Smith Island, Maryland? Well, you’ve got three options—all boarding at City Dock in the town of Crisfield.

There’s the Captain Jason, piloted by Captain Terry Laird. That ship runs daily (except during ice-ups, of course) to both Smith Island and neighboring Tangier Island. Passage with Captain Terry will cost you $25. Terry’s brother, Larry Laird, runs the Captain Jason II, and charges the same as his brother. Then there’s the Island Belle, operated faithfully by Captain Otis Ray Tyler. Call him for details.

And that’s it.

Unless you’ve got your own boat, or you’re one heck of a kayaker, you’re not getting to Smith Island without the help of Captain Otis or the Laird brothers.

Because the fact is, Smith Island is far, far away. It is far, far away even if you live in Crisfield, the raggedy seafood town at the bottom of Maryland’s Eastern Shore that serves as Smith Island’s lifeline to the mainland. To be exact, Smith Island lies a full 12 full miles out in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay. So even when you hop on one of those ferries running out of Crisfield, you’re still looking at an hour-long trip to Smith. If the weather’s bad, or if there’s ice on the bay, the trip might take two hours.

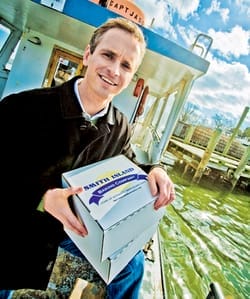

So imagine, for a moment, the trip that Brian Murphy, WG’08, faces on a regular basis—his “commute,” if you will, from suburban Washington, DC all the way to isolated Smith Island. It’s a commute that drags on for four often-frustrating hours, through the snarl of the Beltway, up and over the always-unpredictable Chesapeake Bay Bridge just east of Annapolis, and then all the way down to Crisfield via the two-lane roads of the Eastern Shore. It is 162 miles in all. Not counting the last nautical 12 from Crisfield to the island.

But, soldiering through that journey is just one of the many challenges Murphy, a commodities trader-turned entrepreneur, accepted the moment he decided to move forward last summer with an ambitious plan to open his first business, a high-end bakery, on Smith Island. And sometimes, in the midst of one of those DC-to-Crisfield trips, even Murphy wonders into what he got himself.

“It’s a busted day,” Murphy says of the trek. “I mean, it’s an entire day, gone. I get a lot of cell phone time.”

So why not move the bakery elsewhere?

Why not use the same recipe, but bake the cakes back in DC?

Murphy laughs at the suggestion.

“Because the island is the business,” Murphy says. “It’s the blessing and the curse. I could easily make the hassle go away. I could bake the cakes in a Philadelphia suburb. But then I don’t have the business, do I?”

‘A Big Bet’ on a Struggling Island

Think Murphy is exaggerating?

Think again.

In the months since he launched the Smith Island Baking Company in the island town of Ewell—there are two other towns there, neighboring Rhodes Point and remote Tylerton, which is accessible only by boat—Murphy has seen his startup bakery gain more than a little attention in the press—and not necessarily because of the quality of his cakes. As the press mentions in the Washington Post, Gourmet and various foodie blogs have shown, people are simply fascinated by Smith Island, the last inhabited offshore island in Maryland’s portion of the bay and, in many ways, the last stronghold for a dying way of life.

“I made a big bet on [the island],” Murphy says. “My cousin lives up in Manhattan, doing public relations for the fashion industry. She and I talked about this, and she told me, ‘You know, people would pay me a $1 million to come up with a story half this good.’ I kind of recognized that pretty early on. The island is just a really great story.”

A great story, yes. But not necessarily a happy one. Not recently, at least.

Smith Island is and has always been a seafood island—a place where the men fish for blue crab in the summer and oysters in the winter, and where the women work jobs tied to the men’s daily haul. But as the health of the bay has declined, so too has the island. The bay’s once-abundant oyster fisheries have been so obliterated by disease that populations are estimated to be only 2 percent of what they were 100 years ago. The blue crab fishery, while not in as poor shape, isn’t anywhere near what it once was, either. Though bay crab populations have rebounded in the year and half since a fisheries state of emergency was called in 2008, tight crabbing regulations and hard-to-solve water quality issues almost assuredly mean that crabbing will be down for years to come.

For Chesapeake Bay watermen generally, and for Smith Island specifically, the crash of the fisheries has been devastating. Watermen can’t make what they used to make, and the island’s women, who historically earned seasonal pay by working in crab-picking houses during the spring and summer, have seen employment opportunities dry up, too. Things have gotten bad enough that some island residents have decided to finally give up and head to the mainland. The population on Smith today is estimated at about 300. And dwindling.

Given the bleak backdrop, then, it’s easy to understand why Murphy’s arrival on the island—word about his plans got around pretty quick—created such buzz. After years of seeing jobs and business leave the island, residents caught word that some young guy from Washington was thinking of bringing jobs to the island. Even better, the jobs he was offering were jobs the women of the island knew they could do—and do well.

A native Marylander, Murphy had long known about the famed “Smith Island cake,” a decadent island delicacy—imagine the densest, most luxurious, most perfectly made layer cake you’ve ever tasted; that’s a Smith Island cake—that, partly through word of mouth and partly through the popularity of author Tom Horton’s island memoir An Island Out of Time, had become something of a foodie legend throughout the bay region. Today, the Smith Island cake is the official state dessert of Maryland, and while it may not be true that everyone around the Bay has actually tried a Smith Island cake, it’s probably safe to say that they’ve at least heard of it.

Murphy’s vision, then, was simple, even if he knew making the business work wouldn’t be.

He wanted to open a bakery specifically to produce Smith Island cakes. And he wanted to the bakery to be located on Smith Island. No questions asked. No matter how much of a pain that location would be.

That was the idea he pitched to the Smith Islanders last summer. They liked it.

“We had always wanted to do something with the cakes,” explains Donna Smith, a lifelong Smith Island resident who now works as one of Murphy’s bakers. “But we never knew who to get in contact with to make it work. We knew the obstacles. We didn’t have the funds.”

On the Front Lines

Murphy, however, did. Maybe more importantly, he had the drive—and the know-how, thanks to Wharton—to get the business up and running.

A former commodities trader for Constellation Energy, Murphy left the company, soon after finishing his Wharton MBA, because of what he described as a “culture” change at the company. That change drove many of his mentors to resign, and Murphy ultimately decided to do the same, heading out on his own and founding the Plimhimmon Group, a Chevy Chase, MD-based principal investment firm. The firm’s first portfolio company is the bakery.

The long-term plan, of course, is to grow Plimhimmon and turn day-to-day management of its portfolio companies, the bakery included, over to somebody else (this figures to be true, especially, if Murphy ends up running for governor; he was considering a run, as a Republican, as this story was going to press). For now, though, Murphy is on the front lines, handling almost every single aspect of the business, every single day, for every single cake being delivered to every single customer.

After asking around for a good business manager, Murphy was directed to Kristen Manzo, a former staffer with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation who had moved to the island with her fiancé. He hired her immediately. Then he asked around for a good building—someplace big enough to hold a commercial bakery—and was directed to an empty warehouse building in the village of Ewell. He leased it sight-unseen. Besides, he had no choice; it was the biggest building on the island. He later learned it had a leak and no heat (the heat is fixed; the roof isn’t).The work was just beginning. To save money, Murphy hand-painted not only the billboard-sized sign that stands out back of the bakery, welcoming visitors as they step off the Ewell docks, but also the two signs decorating both the inside and outside of the building itself. He oversaw the design of the bakery’s signature cake tins, contracted with a Chinese firm to manufacture them … then scrambled to find storage for the tins when he realized his bakery wasn’t big enough to hold the entire order. He handles staffing and payroll, does his own media relations work (the Post story, he notes, created an instant spike in sales), coordinates the delivery of supplies to the island, (one of his greatest challenges, given that he relies on those ferries) and, of course, ensures safe transport of finished cakes off the island (the U.S. Postal Service proved unreliable, roughing up the cakes a bit too much, so Murphy switched over to UPS). Basically, Manzo handles the day-to-day operations of the bakery; Murphy handles everything else.

“He’s young, he’s energetic and he’s really interested in making it go,” Smith says. “Anything we need, he gets it to us. Anything we think that can make the business better, we let him know.”

“He’s great with the women,” adds Manzo. “At the first meeting, some of them had questions or concerns, and he would just say, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it.’

‘If We Won’t Eat It, We Won’t Sell It’

Ask Murphy to pinpoint the single greatest challenge of this job and he laughs.

“Well, the obvious answer—the flip answer—is to say that I run a bakery in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay,” jokes Murphy. “Upstream has been a hassle. It’s hard to get people to take you seriously. It’s hard to get boxes made that are right for the product. All of that stuff is just a big hassle. It’s hard to move the ball up-field. I knew getting ingredients to the island would be a hassle. But that said, now I can push a button and order more tins tomorrow. I can get more boxes. And the biggest, most welcome surprise has been the downstream stuff, how easy it is for me to get a cake out, six days a week, at 7 a.m. If you call me at 4 p.m., I can get a cake out the next day just like any other baker. The charm of the island will never be an inconvenience for my customers.”

“The standard we live by on the island, whether we’re talking about layer cakes or crab cakes, is that if we won’t eat it, we won’t sell it,” says Smith. “If we look at a layer cake and we think something is wrong with it, we trash it. Brian has told us to go ahead and do that. We take our time. We want our product to look good. Because we want our customers to come back.”

So far, that’s exactly what’s happened. Sales have been strong from the get-go; stronger, even, than Murphy may have expected.

That was especially true during the holidays, when the tiny bakery was churning out up to 75 custom-ordered Smith Island cakes every day—no small task, given that every cake is made from up to 10 separate layers, each of which needs to be baked individually. Manzo and the bakers were pulling 12-hour shifts. The local ferry captains made extra runs to help out. Still, demand literally outstripped supply; the bakery simply could not keep up with all of the orders coming in, and so some customers had to be turned away.

“Well, I was hoping the bakery would work,” says Missy Tyler, another of Murphy’s bakers. “But how it was around Christmas? I didn’t expect that. The phone just kept on ringing.”

Since then, business has calmed down somewhat, but Murphy says he’s pleased with the company’s performance. He’s also eyeing new revenue streams to make that performance even better. To tap into the island’s small tourist trade—some estimate that up to 30,000 people visit the island each summer, though others say the number is closer to 16,000—Murphy plans to turn the bakery into a destination all its own, an island café where tourists can stop for a bite to eat before heading back to the mainland. He’s also in negotiations with the Baltimore-Washington International Airport, which is interested in selling his product.

Even still, the bakery is a long way from breaking even, and Murphy knows he won’t be handing over day-to-day operations—or outsourcing that brutal commute—to anyone else anytime soon. But he’s not just hopeful that the Smith Island Baking Company is going to survive. He’s confident that it will. In fact, he feels it’s his responsibility to make that happen. First and foremost, he’s running a business, and he knows his first priority is to make the business work.

But he brought jobs to an island that needed them, and he’s seen the positive impact those jobs have made. So he can hardly fathom the day when he’d have to take those jobs away.

Murphy says his grandfather, Robert H. Murphy, was a pioneer in employee stock ownership, and he says he a similar vision for the bakery. He would like to one day structure the business as a C-Corp., and award his employees with stock.

“I carry with me a lot of his vision about the right way to do business,” he says. “I take pride in the fact that my employees like going to work. I like that they are paid a fair wage, and I don’t see that going away. … I tend to believe that principled investments pay off, no matter where they’re made.”