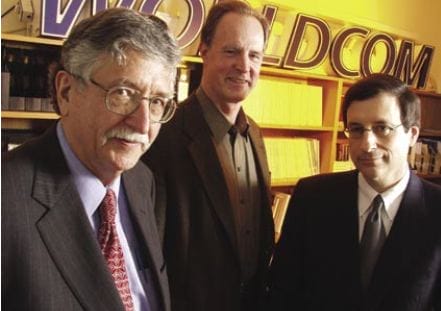

A huge blue-and-white WorldCom sign spans one wall of the sixth-floor conference room at The Carol and Lawrence Zicklin Center for Business Ethics Research where Professor Bill Laufer is discussing the Center’s initiatives. Laufer, director of the Center, displays just a tinge of embarrassment when attention is drawn to the sign and the peacock-colored Enron logo perched on the windowsill.

This hesitation may be because the Center has remained so steadfastly above the fray of the whipsaw of public opinion and headlines about corporate scandals. For three decades, while public outrage has come and gone and come again, Wharton faculty have maintained a steady commitment to rigorous research, pioneering education and thought leadership on business ethics and corporate social responsibility. The School has assembled a brain trust of some of the most respected faculty from diverse departments in this field. This is not a place that runs with the headlines. That may be why this elephant’s graveyard of corporate miscreants in the Center’s conference room elicits a moment of hesitation from Laufer.

In another sense, however, these relics of corporate corruption and greed reflect a central aspect of the Center’s activities:the direct connection between research on business ethics and the world of business. Through far-reaching initiatives with the World Bank, United Nations, and other organizations, this small research center in Philadelphia is having an impact in places like Russia, Singapore, Mexico, and Dubai. Questions of ethics and social responsibility are not considered from a philosophical distance, but rather through a direct engagement with leaders of business, government, and non-profits who are wading through them.

In this context, these unusual conference room furnishings send a strong message. After his brief pause, Laufer says with determination, “They are a reminder that the field of business ethics has unrealized potential and that there remains a fight to be fought.”

Research Driven

This is a fight of research, not rhetoric. While there are many business ethics centers, the Zicklin Center stands out because of its emphasis on supporting and disseminating research. A 2003 report by the Aspen Institute’s Business and Society Program and the World Resources Institute identified Wharton as one of the schools that is “setting the bar for research activity” on social impact and environmental management. “We understand that if we are going to have a significant impact, it will be through research that leads the field,” Laufer said. “Unfortunately, many of the solutions to some very complex problems have been politicized. We have Sarbanes Oxley, exchange reforms, regulatory incentives for good corporate citizenship, and corporations saying how serious they are about matters of ethics and integrity, but not much is known about what really works to institutionalize ethics and control corporate deviance. In fact, with all of the progress made in the field of business ethics, surprisingly little is known about many of its core concepts and constructs, including the notion of corporate social responsibility. There is a dearth of well-conceived and well-executed research, and far less that is definitive.”

The Center’s agenda is designed to offer research that informs these important discussions around the globe. “Politicians, regulators, law enforcement and the private sector are joining hands in ways that suggest a simple governance solution to corporate malfeasance, “Laufer said. “But there is a difference between having good intentions or politically expedient solutions and law reform that has meaning. We fund normative and empirical research that offers a lasting foundation for these discussions. As a small research center, we do everything possible to leverage the research strengths of Wharton in ways that have a broad impact.”

Rise of the Hummingbirds

In an article in the Financial Times a few years ago, Wharton Professor Thomas Donaldson compared corporate ethics programs in the 1950s to hummingbirds. “You didn’t see one often and when you did it seemed too delicate to survive,” he wrote. “Now, these curiosities have proved their sturdiness, flourishing and migrating steadily from their historical home in Europe and the U. S. to Asia, Africa, and Latin America.” Today, there are a half dozen or more active journals related to business ethics, and most business schools have required ethics courses. “It has been a dramatic evolution,” said Donaldson, Mark O. Winkelman Professor of Legal Studies, “and the same thing has happened with respect to knowledge.” (See sidebar.)

Using Donaldson’s hummingbird analogy, Wharton was among the first and most active aviaries for these rare birds. Professor Thomas Dunfee came to Wharton as a visiting professor in 1974, and he designed a new MBA course in business responsibility and regulation, leading to an ethics program that became a model for schools around the world. Research by diverse Wharton faculty was brought together with the founding of the Zicklin Center in 1997. Wharton set the pace, and continues to be recognized as one of the leaders in education and research.

“Business ethics has been taken seriously at Wharton for many years, well before peer institutions saw its critical importance and value,” said Laufer who became director of the Center in 2000. “Tom Dunfee’s vision and leadership resulted in successfully recruiting scholars with sufficient visibility to make Wharton a leading, if not the leading school, in the area of business ethics.”

The importance of the issue is now a given. “The debate is no longer about whether ethics is important,” said Dunfee, Joseph Kolodny Professor of Social Responsibility in Business. “That war has been won. It is reflected in laws and practices. Now it is more a matter of how you do it.”

Taking on the World

To address the issue of “how you do it, ” the Zicklin Center forged new partnerships with the World Bank Institute (WBI)and United Nations Global Compact in 2002. These alliances have allowed Wharton to leverage its knowledge through global events and e-conferences, educational initiatives and joint research projects. “The World Bank Institute and Zicklin partnership is so powerful,” said Zicklin Fellow Alisa Valderrama, who works at the World Bank in Washington, D. C., as the liaison between Wharton and WBI. “It allows the Center to address some of the most compelling and complex issues of corporate responsibility: emerging markets and poverty elimination. It takes an agenda that could be very theoretical and focuses on real challenges. Nowhere does business ethics have more impact than in poverty elimination. It bridges the theorist and practitioner and allows the Zicklin Center to have a global impact from the knowledge it generates.”

The Wharton-WBI initiative has already demonstrated the power of this combination of knowledge and reach to enhance the impact of both partners. “The cooperation with Wharton marks a turning point in our capacity enhancement activities around the world,” said Djordjija Petkoski, head of the Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Program at the World Bank Institute. “It has provided us with direct access to cutting-edge knowledge in research and curriculum development. Partnering with Wharton professors and, equally importantly, with Wharton students has led to increased impact and effectiveness. In the coming months, we hope that this cooperation will allow us to reach Wharton alumni, who may be best positioned to be actively involved in implementation of projects at the institutional level.”

Among many projects, Wharton and the World Bank are working with a major Mexican-based corporation to create business ethics modules for thousands of business school students throughout the country. Zicklin is also working on new modules for the World Bank Institute’s free online program on corporate social responsibility and business ethics, which has already been taken by more than 10,000 government leaders, corporate executives, and students around the world, including an entire university in Nigeria. Their work with Romanian professors in developing a new program on corporate social responsibility led to contributions to the development of new laws on business ethics and corporate social responsibility introduced by the Romanian government. “We are getting the message out on a major scale,” Valderrama said.

The partners also are collaborating on establishing a network of business ethics centers in the Asia-Pacific region and on a micro credit project with young entrepreneurs in Iran. “Here are entrepreneurs who are desperate for knowledge,” Valderrama said. “We are out there empowering people to consider: What is the role of business in your country? The Zicklin Center makes these issues relevant.”

The collaboration has drawn in students from around the world. A recent e-conference on corporate social responsibility attracted more than 1,300 participants from around the world, including students from Peru, Ghana, and the United States. “Part of what we are trying to do is to link these people around the world and share their knowledge, not just high-level practitioners, but empowering young people to take these ideas and put them into action, “Valderrama said. During a video conference on corporate social responsibility in Russia in 2002, students from Moscow joined Wharton peers from Net Impact in Philadelphia. After the event, the Russian students founded their own branch of Net Impact in Moscow and organized a campaign for business ethics to be taught at their university. “This is the kind of connection that this initiative fosters,” she said.

Seeking Knowledge without Borders

Wharton’s work on business ethics has taken researchers to all parts of the world, including studies on Japan, Russia and the former Soviet republics, China, Israel, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Mongolia. (See below.) While research questions in the United States may be more narrowly defined, in other parts of the world, there are sweeping challenges. “One of central questions we are looking at now is the extent to which increasing a commitment to corporate social responsibility and improving corporate governance mechanisms can offset the inadequacy of national governance mechanisms,” Laufer said.

Wharton faculty members are examining many other issues related to corporate social responsibility. Among many projects, Alan Strudler is exploring ethical issues of insider trading, Eric Orts is studying environmental contracts and corporate social responsibility in times of war, Maurice Schweitzer and Jennifer Dunn are looking at confidence and corruption, and Nien-hê Hsieh is working on issues of worker participation and management in corporate governance. Laufer just finished a book on the weaknesses of the corporate criminal law, with particular attention to novel theories of corporate liability. Dunfee recently co-authored an article on corporate boards and ethics programs, and is engaged in separate studies of attitudes about business ethics in Russia and China.

The Center sponsored an impact conference on social screening of investments, followed by a special issue of the Journal of Business Ethics on this topic. This spring, the Center will co-sponsor a three-day conference on the limitations of voluntary codes of conduct in international business with the World Bank and the Zicklin School of Business in New York City. A conference on ethics and the mutual fund industry will follow.

Still, there are many more questions than faculty to address them. This fall, Wharton will welcome its first class of doctoral students to a new Ethics and Legal Studies Program, to help fill the need for researchers and teachers in this area. “The exploding need for teaching, research and business expertise in ethics and law has outstripped the supply of professionals,” Donaldson said. “Alumni and students are very interested in this topic, but what we need are more faculty. Our new doctoral program will be the first to thoroughly integrate business ethics and law, and will immediately become the premier program in the world.”

Rising Student Interest

While the Zicklin Center’s global research is affecting knowledge practice around the world today, its work with doctoral, graduate, and undergraduate students on campus is affecting a new generation of leaders. There is rising student interest in social action on campus, with some 80 to 90 percent of MBA students participating in some kind of community service or social project. In 2002, the Center funded undergraduate research on topics such as perceptions of corruption among Indian business school students, corporate social responsibility in Argentina, business ethics in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and ethical investment. The Center also works closely with students of the Social Impact Management (SIM)initiative, which was created in the fall of 2002 as an umbrella organization for diverse campus activities related to social and environmental change.

Vassilev, WG’05

“Wharton is very student driven in its approach to corporate social responsibility,” said Miro Vassilev, WG’05, one of two SIM Fellows based out of the Center each year. “Students who are involved don’t see the MBA as a transaction experience;they see it as a transformation experience. They want to see something change. Right now, there is a congruence between the goals of the administration and students, and that is resulting in something very exciting.”

SIM held its second annual symposium in October 2003, on “Building Sustainable Enterprises, “and it is working with the UN Global Compact and the Sabanci University in Istanbul on its first international academic conference on global corporate conduct. The conference is designed to contribute to global creation of knowledge around social and environmental justice issues. In partnership with Wharton’s Europa Club, students also are developing a panel of high-level alumni from Europe for the forthcoming Zicklin conference in New York. SIM also will send two students to Geneva to work as interns over the summer on emissions trading and other issues for the UN environmental program, and a new SIM Venture Fund has awarded seed money for projects such as developing an ethics curriculum for Philadelphia high schools and setting up a local chapter of an organization for disadvantaged young adults.

“Every school will take up corporate social responsibility in this era of scandals, but the question is to what depth?” Vassilev said. “Wharton has the oldest ethics program, but one of the youngest social impact management initiatives. It reflects on the culture of the school. We don’t buy into fashion early, but we stick with it.”

He said some students, like himself, are planning to work on social impact projects after graduation. Many others, however, are exposed to experiences that they will carry with them into more traditional corporate roles. “Students exposed to social impact management will have an incredible impact in the future, “he said. “People who stay in business may have a greater impact than those who work in the social sphere.”

Responding to Dramatic Change

This work is more important than ever. “It is very important that leading business people and academic and government people really address this issue of social responsibility, and it is also very important that future business leaders are completely aware of the responsibilities they are taking,” said Jean-Pierre Rosso, WG ’67, chairman of the board, CNH Global NV Netherlands. “The people of my generation have, to a large extent, learned this along the way. Given the nature of society today, the speed at which it works and the awareness of information, it is important that business schools do a better job of explaining the responsibility of business leaders earlier in their careers.”

The implications of research and teaching on corporate social responsibility are far reaching. “If you take the crises that have occurred, you can consider this just a blip or you can think that the world today has changed so dramatically that capitalism is threatened at its roots,” Rosso said. “We should do whatever we can to address this issue and make sure capitalism can evolve and continue to be the best system. If you think it is threatened, we ought to do something about it.”

What are some of the key insights we have gained from research on corporate social responsibility over the past three decades?

“One of most surprising conclusions over the last couple of decades, a discovery bolstered by lot of research, is that codes of ethics may be important but actually are rather a small part of what helps an organization succeed,” said Professor Thomas Donaldson. “Codes have not been correlated well with increased ethical behavior; there is actually a slight negative correlation. “What is important? Probably the most dramatic correlations are with reward systems. It is also important to have a means of communicating upward, such as channels for employee complaints or whistle-blowing. “More important than what you say is what you do,” Donaldson emphasized.

Another insight from the research is that law is an ineffective mechanism for ensuring ethical behavior, even in countries with fairly well developed legal systems. “What’s known inside the industry races far ahead of the law – highly leveraged derivatives, off-balance-sheet transactions or hedging are almost like advances in medicine,” Donaldson said. “The public mind has not grappled with these issues.”

Research also has indicated that certain ethical characteristics improve efficiency. “The old joke is that ‘business ethics’ is an oxymoron, like jumbo shrimp, but ethics is critical for long-run efficiency, both for the firm and the nation state,” he said. Where trust is lacking, for example companies have to turn instead to monitoring, which is expensive and inefficient. “Adam Smith was the first guy to make this point, showing how this remarkable system of capitalism has the ability to take the self interest of people and direct it toward the common good.”

Philip Nichols’ global studies have found a remarkable similarity in perceptions of corruption around the world.

Associate Professor of Legal Studies Philip Nichols didn’t go to Mongolia looking for additions to the remarkable collection of fur-lined and ornamental hats perched above his bookcases in his Wharton office. The hats were just a byproduct of his search for insights on corruption as a visiting professor at National University of Magnolia, in Ulaanbaatar, a pursuit that has also taken him to Uzbekistan, Belize, Senegal, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bulgaria, and other parts of the world. In fact, he didn’t even set out to study corruption more than a decade ago, but conducting research on business in developing economies kept coming back to this central issue.

“What I was initially interested in is how these countries are changing to effectuate a greater number of relationships outside of their particular jurisdiction, “said Nichols.” I started looking at things like privatization and foreign investment laws, but the more time you spend in any of these places, the more you realize corruption is at the bottom of everything. If you are really serious about studying these countries, you have to be serious about studying corruption.It touches everything.”

Corruption is often justified by both bribe-givers and bribe-takers as a culturally accepted and even expected practice, but Nichols’ global studies have found a remarkable similarity in perceptions of corruption around the world. For example, a study with a colleague comparing views of corruption of students in Mongolia and Bulgaria found that they had nearly identical views. “This does not support the idea that corruption is a completely relative cultural construct,” he said. “It supports the idea that there are universally shared ideas of what corruption is. I have yet to find a place where people like corruption or think it is a normal thing. People say: ‘It becomes a way of life.’ But if you live in a war zone, war becomes a way of life. It doesn’t mean that you like it.”

While there are common views of what constitutes corruption, Nichols’ travels have shown that the nature of corruption is quite different from country to country. “Corruption is incredibly textured,” he said. “It is not straightforward. It is different in every place I’ve ever gone. That is something a lot of people overlook.”

Working in countries with corruption often means being directly exposed to it. Nichols has been stopped by Russian policemen, beaten up by border guards in Africa after refusing to give them his socks and has sat for hours on a bus with other passengers in Eastern Europe after the driver unsuccessfully demanded a bribe to continue.

One of the biggest changes during the time he has studied this topic is the willingness of companies and international financial institutions to discuss it and address it. “In the past, this was something they didn’t talk about, “he said. “Now it is something they all talk about.Businesses, I think, are the greatest potential source of really effectuating a global change. They are organized, they are funded and they have a lot of incentive. They are seeing potential markets in Central and Eastern Europe degrade substantially because of corruption and seeing their own internal management systems degraded. When the supply dries up, the demand will dry up.”

He’s looking forward to this day. “I can’t wait until I’m out of business, when there is not so much corruption anymore, “he said. “Then I can get back to studying these other topics.”

A Perspective from Europe

The Wharton Alumni Magazine recently asked Klaus Zumwinkel, WG’71, chairman of the board of Deutsche Post World Net in Bonn, Germany, for his perspectives on how corporate social responsibility affects his business. In the following Q&A, he shares his insights.

What are the major issues related to corporate social responsibility facing your organization?

Deutsche Post World Net is one of the leading companies in the international transport and logistics market. Our customers trust our global reach when it comes to solving logistics challenges. The financial markets expect us to provide solid governance, long-term shareholder value, and sustainable growth. Thus, we have to make sure that the confidence they have gained based on our business performance is not derogated by our business practice. It is not only the business and financial community which expresses its expectations but also stakeholder groups and the wider public. Thus, it will be crucial to guarantee the global implementation of our core values and principles regarding corporate social responsibility (CSR)and to live up to them wherever we operate.

I am convinced that environmentally and socially responsible behavior can affect profitability in a positive way. Deutsche Post World Net has been admitted to the FTSE4Good Index of Socially Responsible Investment. This demonstrates that our approach to responsible business practice is also rewarded by the financial markets.

What are you doing to address these CSR issues in your organization and in the broader society?

Within Deutsche Post World Net we have started to integrate CSR into relevant corporate guidelines and policies. For instance, our international purchasing guidelines explicitly refer to the corporate values and international commitments such as the nine principles of the UN Global Compact. We will also promote cross-functional and cross-departmental teams to deal with the responsibilities deriving from CSR. We address the broader society by means of regular stakeholder dialogues and are also engaged in a number of partnerships with internationally operating institutions. For instance, we have worked with the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) to offer humanitarian assistance after the Earthquake in Bam, Iran.

How has concern about corporate social responsibility changed over the course of your career?

In my opinion, corporate social responsibility has a solid history in business. During my career I often encountered a strong CEO commitment towards community involvement, philanthropy, environmental management, and humanitarian assistance. However, this commitment was largely built on the founder of a company, the patron, who largely engaged with local communities through social investments. Increasing legal obligations in the social and environmental field in Germany and Western Europe have shaped business performance and responsibility towards CSR. Issues of corporate social responsibility have changed over time. The industry is facing growing stakeholder expectations, which increasingly encompass social and ethical as well as environmental responsibilities embedded in international law and best-practice voluntary codes, such as the UN Global Compact or the Logistics and Transport Corporate Citizenship Initiative (L&TCCI) of the World Economic Forum. In addition to the environment, these codes collectively address human rights, labor standards and governance. Deutsche Post World Net has committed itself through its subsidiary DHL to adhere to these principles, and we take this effort very seriously.

In what ways is the view from Europe on this issue distinct from other parts of the world?

There are, in fact, different cultural traditions and standards. Social and environmental legislation cover a broad spectrum of activities and commitments that do not exist in other parts of the world. The challenge for companies operating worldwide is to develop common standards and business principles that empower our local and regional management to act accordingly. We have developed a core set of values for Deutsche Post World Net which shall help executives to establish a moral compass for business practice wherever they work. These values include elements found in both Western and non-Western cultural traditions. We are now tackling the issue of setting up a code of conduct which provides clear direction about ethical behavior. However this code of conduct must also leave room for individual judgment in situations requiring cultural sensitivity.