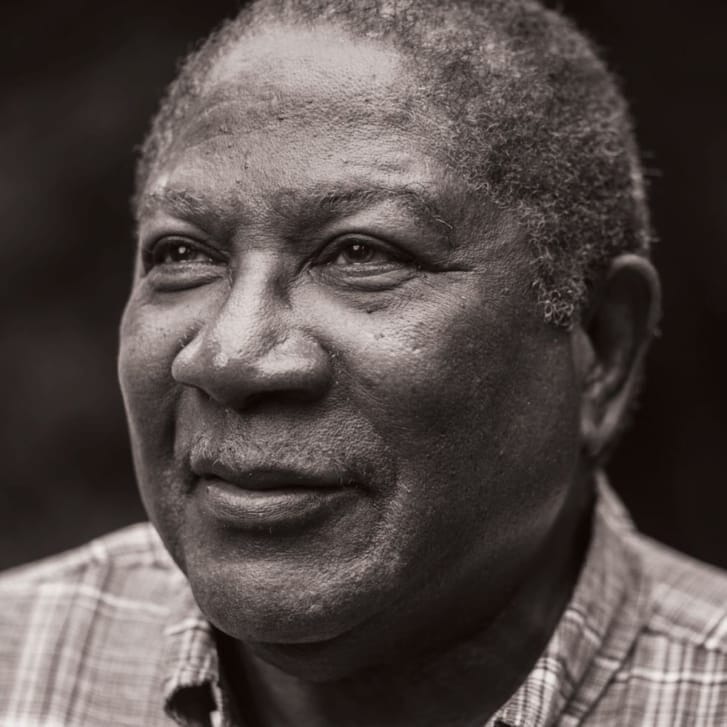

Adam Grant is running a bit behind for a chat about his new book, Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things, and instead of silence on our virtual call, or music made for elevators, there’s a plucky acoustic tune playing — with lyrics about the frustration and the promise of being on hold. Leave it to the award-winning management professor to turn the most mundane moment into an opportunity for callers to think while also being entertained. Recognizing overlooked opportunities is one of the essential themes of the New York Times best-selling author’s latest work, which, through his usual blend of storytelling and research, aims to help readers reach new heights and grow along the way. During our interview — with Grant, it’s never a one-way conversation — he shared his most surprising research, how he draws inspiration from a sports star and a Harlem chess team, and why asking for feedback is a mistake.

Wharton Magazine: This is likely the first publication by a Wharton professor that begins with a quote from Tupac Shakur. Aside from that, what inspired this book?

Adam Grant: There are so many relevant moments, but one was interviewing my college diving coach, Eric Best, for a podcast on perfectionism. He said, “You got farther with less talent than any diver I’ve coached.” My first reaction was: Wow, that’s a backhanded compliment. But as I reflected on it, I realized that my proudest accomplishments have not come in the areas that came naturally to me. They’ve come in the areas where I’ve had to overcome significant obstacles. I realized that a lot of us really judge our success by our achievements as opposed to thinking about the progress we’ve made. That’s a huge problem, and I wanted to understand it better.

WM: You tell a fantastic story in the prologue about the Raging Rooks, an inner-city chess team. How do they represent the essence of Hidden Potential?

Grant: These kids are poor racial minorities in Harlem, and they’re going to compete against these fancy private schools that have built the chess equivalent of Olympic training centers. The odds are impossibly stacked against them. One of them learned chess from a drug dealer. And yet these kids go from chess newbies to national champions. What they taught me, which is consistent with the research, is that character skills are even more important than cognitive skills: the discipline, the determination, the proactivity, the pro-social teamwork that they did. What’s really powerful about that story is they’ve got a coach, Maurice Ashley, who sees potential in them that they didn’t see in themselves, and, even more interestingly, their own parents didn’t see in them. That’s what this book is about: We don’t just underestimate ourselves; sometimes the people who know us best underestimate us, too. And now that we’re talking about this, I should have written that in the book!

WM: What surprised you most in your research?

Grant: There were a lot of surprises. If I had to pick a category, it was education — it turns out that having the same teacher for multiple years is good for learning. That is the exact opposite of what our entire education system is built on, which is that teachers are supposed to specialize. As soon as I read it, it made perfect sense — teachers need to specialize in their students, not just their subjects, so they can build relationships and grow together. I think it calls for a radical redesign of our primary and secondary education systems. It’s a small effect, but one of the things I know as a social scientist is that small effects across the large population can be extremely meaningful. What surprised you the most? I’m curious.

WM: Reading that learning styles are a myth was really mind-blowing.

Grant: That was the other education finding I was thinking about. I first read the debunking of learning styles maybe 15 years ago, saying that there’s no credible evidence learning styles are a real thing, let alone that tailoring to them is good for your learning. It was one of the best overturnings of my assumptions that I’ve ever experienced as a psychologist. I’m naturally a verbal learner and verbal thinker, so it’s obvious that I’m going to learn better when I read. Then I read the research. Nope! Not only do you not learn better that way; sometimes, you may learn worse that way, because it comes too easily to you — you don’t have to work at it, and you may not internalize the knowledge as much. That was stunning to me. I guess it was an early seed for this book, in a way.

WM: One of the most challenging concepts might be the idea of “becoming a creature of discomfort.” Especially in these times, when so much is designed to make our lives easy, provide instant gratification, and minimize troubling thoughts, how do you convince people to leave their comfort zones?

Grant: I think comfort is boring. My favorite question to ask people when this comes up is, “Tell me about the greatest growth experience you’ve ever had.” Most of them end up describing an uncomfortable experience. They connect the dots pretty quickly. It doesn’t mean you should always go outside your comfort zone, or so far out that you feel disingenuous or inauthentic. It does mean, though, that sometimes choosing comfort impedes growth. And you don’t want to stifle your progress. Have you watched the Steph Curry doc?

WM: No, not yet.

Grant: It’s like an advertisement for the character skills in Hidden Potential. My favorite scene was, he’s in high school and he’s a great shooter, but he shoots from his hip, so he’s getting blocked left and right. His dad says to him, if you want to play at the next level, you’ve got to re-engineer your shot. Curry then spends the next three or four months miserable. Everything feels wrong. But he’s so determined to improve his game that he’s willing to tolerate the discomfort to reach the next level. People who don’t do that often stagnate.

WM: Curry also illustrates the concept of “deliberate play” in his training, which you discuss in the book. How might that apply to tasks that aren’t related to sports or creative pursuits?

Grant: Deliberate play is the combination of practice and play, where you take the skill you’re trying to build, break it down into core elements, and make those elements fun. People will hear that and say, “All right, gamification — are we gonna take a bunch of boring tasks at work and try to convince people they’re fun by adding bells and whistles to them?” The answer is no. Deliberate play is about actually changing the learning or the practice itself to make it enjoyable, as opposed to just adding some features that try to trick you into enjoying it. The example that stood out for me was an experiment that Justin Berg, Dan Cable, and I did at a hospital. We gave health-care workers a chance to reframe the purpose of their jobs. A nurse who gave kids allergy shots decided to start introducing herself as Nurse Quick Shot. That elicited a completely different reaction from the kids and their parents — it was more pleasant for them and more pleasant for her. When health-care professionals got to infuse a bit of deliberate play into their work, their burnout dropped.

WM: Is there anything you discovered in the process of researching and writing that you’ve applied to yourself?

Grant: There are immediate rewards of writing a book, like the joy of finding the story that pairs with the research. Then there are rewards to come after the book, which include seeing your own hypocrisy. [laughs] I realized I wasn’t consistently applying the evidence around the value of asking for advice, not feedback. I had gotten into the habit of saying, “What feedback do you have?” I was getting a bunch of platitudes, and I was frustrated by it. After I finished the chapter, I thought, wait a minute — why am I not asking, “What’s the one thing I could do better?” So I’ve stopped asking for feedback. I ask how I can improve next time.

WM: You dedicate the book to your late Wharton management colleague, Sigal Barsade. How did she and her research influence the book, and you?

Grant: Sigal was a tremendous believer in hidden potential and someone who went above and beyond to help people realize their hidden potential. One of our annual rituals was reading the applications to our PhD program. Sigal was consistently the one who would pull out somebody who didn’t quite meet the threshold — for example, their GRE quant score was marginal, but they wrote this interesting, creative essay. She would not just want to talk about that candidate. She would email them asking for more writing samples; she would get on the phone with them. In a couple of cases, we admitted students who weren’t on the radar, and they ended up doing great things. Sigal was even a donor to a charity for blind donkeys. She felt that a donkey that couldn’t see could still have a better life. If that’s not what seeing hidden potential is all about, I don’t know what is.

Published as “How to Reach New Heights” in the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Wharton Magazine.