It’s been about 20 years since a powerful idea came along and galvanized executives to invest in changing their business.

But people keep trying to churn them out. Many business books get published every year—very few of which get any traction—and tens of thousands of young people study business in colleges and MBA programs. The students are young, but most of what they learn is not.

I ought to know because I teach strategy and entrepreneurship at Babson College. I’ve been in the same room with the people who came up with those big ideas but none of their brilliance rubbed off on me.

The first of these ideas was from Harvard Business School strategy guru Michael Porter. His ideas about why some industries are more profitable than others, and how businesses can win in the markets in which they chose to compete, came out in 1980 and 1985, respectively. But those ideas are still taught 30 years later.

Porter has continued to write books and articles about other topics that, sadly, do not seem to have gotten the same level of traction as those early ideas:

• Five forces (economic factors like the bargaining power of customers, the strength of which can affect an industry’s average price and profit margins).

• Generic strategies (such as being the lowest-cost producer or a differentiator that can charge high prices).

• Value chain (a map of a company’s activities such as manufacturing or purchasing).

I worked with Porter on my first project at his now defunct Monitor Group, and before that, I worked with Index Systems, a consulting company co-founded by a handful of MIT Sloan School professors. In 1993, a decade after I left, Jim Champy, who hired me at Index, and the late Michael Hammer, one of my MIT professors, wrote Re-engineering the Corporation. This book started a wave of consulting projects—companies and governments were frantically paying more than $1 billion to consulting firms that could help them re-engineer their operations—that is, change processes to lower costs or deliver better service. I remember watching Hammer deliver his stump speech—a jazzed-up version of his MIT lectures in which he waxed eloquent about the idea of starting with a clean sheet of paper—to a rapt crowd of more than 1,000 people in Boston.

Unlike Porter’s ideas, which live on in business schools, re-engineering is no longer a thing. But it was an example of a business idea that really took hold in the minds of executives and drove significant change.

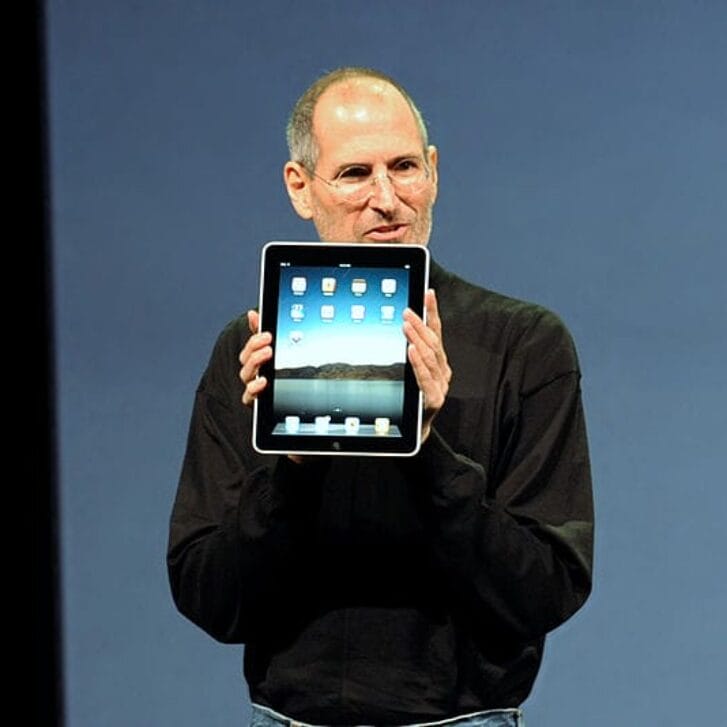

Since then, not so much. To be sure, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen’s notion of disruption—as first described in his book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, remains a buzzword. Though he has started a consulting firm, Innosight, I remain to be convinced that his ideas can shield big companies from disruption.

Tom Davenport, who holds the President’s Distinguished Professor of Information Technology & Management at Babson, challenges the thesis that business ideas are dead. He argues that the sales of his book, Competing on Analytics, were excellent and that “the analytics and big data movement is a big business idea today, and that companies are having a high level of success with it.”

To see if Davenport is right, I would like to conduct a survey of how many big-company CEOs are investing heavily in big data and analytics.

Pending the outcome, my hunch is that there are three reasons for the demise of business ideas:

• Risk-aversion. Most executives seem to be stuck in a risk-averse pattern, and that may make plenty of sense. After all, in 2013 corporate profits hit a record $2.1 trillion and stocks soared to record levels for all U.S. markets except the Nasdaq. Why take a chance on something new when the current approach is working?

• Fad burnout. It’s possible that many of the executives who run big companies now were involved in the 1980s and 1990s waves of business fads. They saw how these “transformative” ideas followed a pattern of great enthusiasm, time-consuming offsite meetings and big consulting fees, only to fail to deliver meaningful results. Perhaps big business ideas will not come back until that generation has retired.

• Lack of clever idea generators. My guess is that the professors and pundits who strive to invent the business ideas are simply not clever enough. For a new business idea to take hold, it must be like a successful startup—find customer pain, prove that it can alleviate that pain better than any idea out there, ride strong underlying market trends and boost results for consumers.

While it would not shock me if some unknown genius is poised to launch a powerful new idea onto the business world, that idea will need to overcome considerable hurdles in order to prevail.