We spoke with mythical independent filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik (a.k.a. Eric de Guia, WG’67) during a rare return to the University of Pennsylvania campus. After a stint at the OECD in Paris, he embarked on a noncommercial film career for three decades and is now recognized as the “Father of Filipino Indie Film.” He is best known for Perfumed Nightmare, a witty film on American cultural influence introduced to the U.S. by Francis Coppola. An incurable romantic, he has also immersed himself in a tribal village, sharing user-friendly video to preserve its rich indigenous culture. For his lifetime achievements in arts and culture, Tahimik was named Laureate of the Fukuoka Prize 2012 (a mini-Nobel prize for Asians). Below is an excerpt from our Q&A with a very out-of-the-box Wharton Grad.

WHARTON MAGAZINE: We recently ran an article about Wharton alumni in the art world, and about how they are applying what they learned at Wharton to their endeavors. Do you find that you use what you learned at Penn?

KIDLAT TAHIMIK: When I chose to be an independent filmmaker (not preoccupied with blockbuster movie-making), I had to deal with some contradictions within myself. My Wharton education had built in an “efficiency obsession”—a.k.a. maximum gains for a given time-effort input. So, my earlier endeavors and dreams were MBA-framed: making it good and achieving it efficiently. You learn those principles at Wharton: optimize further those efficiency models evolved by folks before you (yes, the case studies …) measured by ROI or other formulas.

Choosing the indie film career, my maximize-ROI mindset had to undergo three decades of reprocessing. My newly awakened cultural concerns basically showed me just how our [Filipino] culture has not been allowed to flourish because, once upon a time, we were colonized by Spain and by America. (“Filipinos spent 350 years in a convent and half a century in Hollywood, as one writer put it.) This cultural circumstance had become important in my mind: seeing clearly how our elite (including myself) picked up the Western models, at the expense of the creative richness we have in our local culture. I’m not a xenophobe; I don’t expect us to stay in the Stone Ages. For all our efforts to modernize, there is still a lot of ancestral wisdom relevant in today’s world that shouldn’t be sacrificed at the altar of efficiency.

Even today, Al Gore is quoting Chief Seattle or some Amazon chief. It’s because the world has gotten out of balance. There’s too much abuse of nature because the efficiency obsession has made us forget our basic connection to Mother Nature. Culturally, we’ve lost our brakes. Certainly these eco-wisdoms from the old cultures should be dug up again.

WM: How does that translate into your filmmaking?

TAHIMIK: When I chose to do films, if mega-profits were my only motive—I’ve nothing against making a reasonable profit—but if that were my only goal, then I would do only sex/violence blockbusters, right? … The formula [for the Hollywood model is] S + V = P. Sex plus violence equal profit. … Unfortunately, many local stories are not being told. Whether I’m an MBA or not, objectively, there’s some intangible wealth (values, history of our tribe, spiritual framings) that should not be swept aside—just because we want to be an economic dragon or we want to be major players in the globalization game. If more MBAs appreciated the Gross National Happiness nuances of Bhutan, the 2008 crash might have been curbed.

WM: Did you feel this way at Wharton?

Kidlat Tahimik (a.k.a. Eric de Guia, WG’67) with valise in hand at the Manila airport on the way to study at Wharton

TAHIMIK: With hindsight, Wharton was a detour in my artistic track. For my undergraduate major, I had taken theater at the University of the Philippines. … Because I was accidently elected president of the student government, I thought I was presidential timber. … Some strange voices whispered to me, “Developing countries need economists not artists.” Instead of pursuing my MA in theater, I opted to apply at Wharton. Of course, we’ve had people like Prime Minister Havel in Hungary, who was a poet. My old artistic yearnings would later haunt me—while working as a consultant at the OECD in Paris—long after I got my MBA.

WM: What did you study during your MBA?

TAHIMIK: Somehow I got into international finance. My MBA thesis was on debt servicing problems of Third World countries. I remember my advisor was Dr. Charles Whittlesey, a nice old Quaker who was once a member of the Federal Reserve Board.

My thesis opened with a word from Shakespeare—to introduce debt-default in international finance. Shylock, in Merchant of Venice, is pushing to collect a pound of flesh from Bassanio—whose non-MBA profit-projections to repay his debt are imperiled. His goods, aboard ships at sea, had sunk in a storm. So I put in that “alas-woe-is-me” soliloquy: your revenue-generating goods are subjected to some fluke of nature, and now you can’t pay your debt. That’s the problem of Third World countries: crop failure, coup d’états … anything that disrupts your major export crop. … At that time my artistic right brain was still bubbling. I’m proud of that theatrical quote … but I wouldn’t show you the rest of my thesis!

WM: When did you go from being an economist to an artist?

TAHIMIK: While I was in Paris [with the OECD], I was writing comparative fertilizer distribution studies in the Third World. Because of the Green Revolution, increasing harvest yields per hectares was the big goal of World Bank and donor countries. That became my forte, so today I’m still footnoted as a fertilizer distribution “expert.” But I began feeling an urge to apply such expertise to my creative fertility.

One summer, I went glacier trekking in Norway with OECD friends. A farm at the tongue of the glacier titillated my dormant artistic fertility. I asked the farmer if I could work half-day pitching hay. And in the afternoons I would type my play about economic independence. … At summer’s end, I got my first draft laid out. But when I went back to Paris to my nine-to-five work, I couldn’t find time to focus on my play.

That’s when I decided, OK, I’d better take a two to three-year sabbatical to finish the play. Or why not a permanent sabbatical to answer this urge to shift to another track? But, I’d need to earn a quick buck. So that’s where I saw the Munich Olympic Games as an opportunity.

Olympiads raise money letting you exploit the Olympic mascot or Logo. … You can use these symbols on T-shirts, key chains, lighters … any kind of kitsch you can think of. During the ’72 Munich Olympics, their mascot was the German dachshund. A cute sausage-looking dog named Waldi.

WM: Then what happened?

TAHIMIK: The Olympic committee approved my idea to make the dog in Philippine translucent shell—painted in official Olympic colors—with two dozen shells to make wind-chime sounds. So I had 25,000 Waldis made, cottage-industry style. By the delivery date, the families in the rural areas had gotten so good, they had an extra 20,000 dogs.

But the solid Olympic order was only 25,000. They said, “Please take the dogs on commission. What you can sell, just remit to us because we trust you.” So the 20,000 Waldis went by boat to arrive in the middle of the games. The original order flew with me.

My shell wind chimes sold briskly. I disposed of most Waldis in the first week of the Games with a lot of reorders for the second week. And then the Munich hostage crisis happened.

Like Bassanio, technically, I was bankrupt. Unlike Bassanio, the ships had arrived. But the 20,000 dog … I couldn’t sell anymore in Munich. … I had to move into an artists’ commune (after five years in a chic Quartier in Paris). So in the next three years, I became a sidewalk vendor, hawking my dogs at flea markets in Paris, Oslo, Vienna, Edinburgh. The final 2,500 Waldis were unburdened at Cannes—bought, by a Dahomey beach hawker—to sell during the film festival.

WM: What happened to you in the commune?

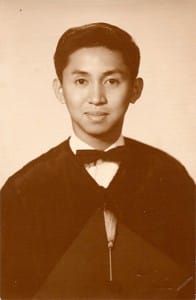

Kidlat in his 1963 high school graduation photo, as president of the student government

TAHIMIK: In the commune, well, I had to deconstruct myself. I learned a lot of low-consumption economics at the personal level—recycling old materials and do-it-yourself chores like chopping wood for the winter fireplace. There I met my wife, a stained-glass artist. We had our first kid. Also, I met a crazy film student. … I kept helping him carry his tripod, load his cameras, drive him, whatever—but I was absorbing every detail of the craft I could. … He asked me and a Brazilian girl to practice some lines for a video exercise at his school. His teacher was sick that weekend. The substitute teacher was Werner Herzog. You’ve heard of Werner Herzog?

WM: The famous German director?

TAHIMIK: After we did the exercise, Herzog asked, “Are you a professional actor?” I said, “Me? No. I just did this playfully.” “Ahhh, sehr gut … Very good. I hate professional actors.”

Well, two months later he came to our commune [and] asked me to play a role in his film, the Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, which won a prize at Cannes in ’74. Being immersed in that kind of Indie film setup, I then decided, “Yeah, I too, want to tell my own story … on 16mm film.”

The next year, Perfumed Nightmare, my debutante film “happened,” without any film training as director. It was made without a distilled script. It was a very crude film, described as a “primitive film” in a New York Times rave review. … It won the Critics Jury prize at the Berlin Film Festival.

WM: And your film career just launched off from there?

TAHIMIK: Yeah. By that time, I’d got my feet on artistic ground again. Lets clarify that word “film career.” Yes, it was launched—not with MBA profits at the box office—but with critical acclaim.

A full-length flick, Perfumed Nightmare, all 90 minutes reached the finish line—with $10,000 production costs. Of course, the direction, cinematography, editing, production design were by Kidlat Tahimik. And guess who was the main star? Kidlat—the cheapest talent available! Its very hard to launch an unknown Indie film by an unknown filmmaker. Francis Coppola liked the film and introduced Perfumed Nightmare in America under the Zoetrope Studios banner. The endorsement encouraged art cinemas to book. It didn’t make big bucks—but it was good exposure for a primitive film.

WM: When did you take the name Kidlat Tahimik?

TAHIMIK: When I started my first film, I gave that name to my main character. Kidlat means “lightning.” Tahimik means “quiet.” In the two years shooting, acting, editing, I must have tranced myself into becoming the character of a Quiet Lightning. (Counterpoint of “a lot of sound /fury signifying nothing”).

WM: You were named a 2012 Laureate by Fukuoka Prize, considered a mini-Nobel Prize for Asians. In your acceptance speech, you credited “cosmic detours” for helping you arrive there. Can you explain?

TAHIMIK: Well, “cosmic detours” are … it’s kind of a mind frame that I’ve allowed myself to trust, maybe, it’s something particular to my life or to Philippine culture: a tacit trust in a benevolent cosmos that will eventually provide a just ending for you, even if things look miserable at the moment.

In my acceptance speech, I pointed out that my printed CV was misleading—for it didn’t mention my many decisions in life, daring to try another track. No, I didn’t stay on track. I felt I was getting the prize for “straying on track.”

WM: In researching for this, we also found an article where you claimed to tear up your Wharton MBA diploma. Is that true?

TAHIMIK: I did tear up my Wharton diploma. But let me assure you—it wasn’t a blanket condemnation of the MBA program. My symbolic act was in relationship to myself. I was tearing down that bridge or burning a bridge to make my transition into an artist complete. It’s always easy to backtrack and, you know, to go back to something, just because you’re armed for it.

Not that I was afraid to fall back because it’s black. (Although I felt that way about a lot of those Wall Streeters in 2008.) It really wasn’t a judgment call. Just in terms of myself: “Can Kidlat be a much more productive citizen, a much more contributing, global individual, if he practices something he enjoys?” So in this sense symbolically, I threw [away] my diploma … or cut an umbilical cord.

I’m glad you asked me because I was thinking, “Should I mention the diploma or not.” It was an extreme act, but … I didn’t want to make other people uncomfortable with that.

WM: Are you still connected to the Wharton community?

TAHIMIK: Well, I live in Baguio, which is far away. Most of the Wharton alumni are in Manila, where banks and big corporations are. A lot of them were college buddies, even before I went to Wharton. A lot of them I met in Wharton. Occasionally, I still meet people who approach me and say, “I’m also a Wharton, I’m an attorney.” It’s like they’re saying, hey, we’re of the same tribe. And I value my having hanged around Dietrich Hall a few years. It’s not a waste of time—to find out what you’re not cut out to be.

After my house burned in 2004, I happened to go through some old papers, and I found a “Wharton-Grad” newspaper. The centerfold showed who were the candidates for WG student government. A picture of a wannabe vice president grabbed me: “Wow, was that Eric in a three-piece suit carrying a valise?”

So I’ve shed that cocoon of MBA dreams, and I yet have to fully evolve to Kidlat Tahimik—that Quiet Lightning. I’m happier in my new self (and certainly more comfortable in my tribal g-string.) But I can still enjoy a good beer with my Wharton colleagues who are CEOs of banks. And I think they enjoy it … to have a strange fellow among them during MBA reunions.