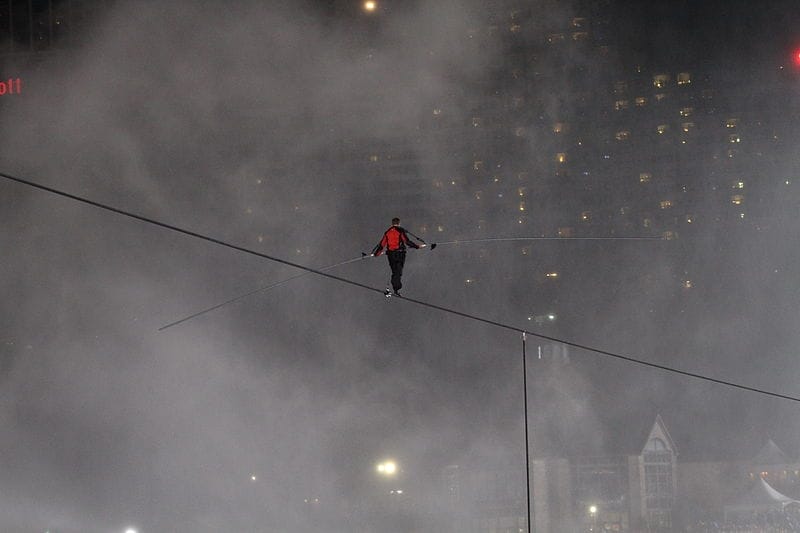

Everybody has been buzzing about Nik Wallenda and his daredevil crossing over Niagara Falls last week. Elsewhere in the world of sports, the USA gymnastics trials for the Olympics will start later this month, and there’s nary a whisper about it. This difference in public interest/attention makes me think about the difference between the fields of economics and marketing: economics is like a high-wire act, and marketing is equivalent to gymnastics. Let me explain.

Economists are an interesting breed. They have their heads in the clouds, dreaming of a magical world where people are rational, markets operate efficiently, and all kinds of other strict rules apply about what’s right and wrong. In their vivid imaginations, they see upward-sloping supply curves, downward-sloping demand curves, and all the implications that arise from these and other assumptions. They’re not particularly troubled by facts, often because the actual “rubber meets the road” data that would support or refute such assumptions are hard to find—especially when they’re too busy balancing their delicate curves in a manner that often seems to defy the laws of physics.

Will she stick the landing? Photo credit: Raphael Goetter.

Occasionally, economists encounter phenomena that don’t seem to comply with their balancing act – much like a gust of wind endangers the tightrope walker. That’s when their real skills start to show. They conjure up new assumptions and clever twists on old ones to prove that seemingly irrational phenomena are, after all, quite rational. Balance is restored once again. Well-written books like Freakonomics beautifully demonstrate this blend of art and science. It is wonderful to behold such mastery, and the skills required to stay safely perched up high are quite considerable.

In sharp contrast, marketers—like gymnasts—start and finish with their feet on the firm ground. The marketer’s desire is to understand the way the world really works, not how it should work under a shaky set of assumptions. Marketers and gymnasts also emphasize the need for balance, but in their case this word means something different than it does for the high-wire economists. Much of the balance for a marketer/gymnast arises from the need to be quite good at each of several different tasks. For the gymnast, this means achieving excellence across a variety of physical challenges (e.g., floor exercise, vault, parallel bars, etc.); for the marketer, it means mastery across a variety of academic disciplines (such as statistics, psychology, anthropology, sociology and—yes—economics). Overspecializing in any one of these areas is a path to sure defeat; the key is to develop a broad set of skills to ensure that you can take on all the twists and turns required by the problem at hand, while always landing safely on two feet. A marketer wants to “stick the landing” by offering an implementable solution to a real problem, not an ivory-tower explanation that merely proves that the world is still rational.

Because marketing/gymnastics is so deeply rooted in reality, it is gritty work that doesn’t generate the same “oohs” and “aahs” as a tightrope performance. People look up to economists and down at marketers, just like they do when their athletic counterparts are performing. Economists get to rub elbows with presidents; marketers get to sell more deodorant. Nik Wallenda gets a prime-time special on national TV and marvelous movies have been made about other high-wire heroes such as Philippe Petit (Man on Wire).

Can you name a movie about a famous gymnast?

Likewise, it’s easy for business leaders to name many economists, but how many can name even a single marketing professor? (I guess I should give up hope that they’ll make a movie from my new book, Customer Centricity: Focus on the Right Customers for Strategic Advantage from Wharton Digital Press).

OK, I admit it. While I’m proud to be a marketer, I do suffer from a bit of econ envy, as do many of my marketing brethren. It’s not that we feel intellectually inferior to our economist cousins; it’s just that we wish we could get some of the glory and attention that seem to come so naturally to them. We respect their work quite a bit (in part because our field derives some of its intellectual origins from theirs), but we hope in vain that they would share some of their limelight with us.

But when I stop being wistful about such matters, and get back to work, it’s all worthwhile. I genuinely enjoy the challenges of describing markets and consumers as they really are, not as they should be. I appreciate the opportunity to learn and combine different skills to solve complex real-world problems. I’m glad that companies come to me when they are looking for tangible recommendations and measurable solutions.

And while I know there will never be a Nobel Prize for marketing, at least I can draw some consolation that gymnasts can compete for Olympic gold, unlike the folks who teeter on the high wire.