James DePreist was lying in bed, stranded, in a Bangkok hospital ward. Stranded because he could not reach his family back home. Stranded because the State Department, which had sent him to Thailand in the first place, would not send a plane to bring him back. And stranded, in the most literal sense, because of his new disability: he was paralyzed below the waist.

The year was 1962. Just days before, the 26-year-old DePreist had come to the life-altering realization that, despite his earlier ambitions for a career in law—and despite his undergrad degree from Wharton, and his master’s degree from the Annenberg School—he wanted a life in music. He would be a conductor—the Bernstein of Philadelphia. He was sure of it.

Then came polio. So as he lay in that hospital bed, cut off from the world and unable to get himself back home, he couldn’t help but wonder if the musical world would ever be ready to accept a disabled conductor. “I had decided what I wanted to with the rest of my life, and how I wanted to commit myself, and I was sure that this is the path,” DePreist recalls. “But now I had this blockage, and I realized it was something that may indeed prevent me from ever doing what I wanted to do.”

Suffice to say, DePreist’s disability—he would never walk again—proved to be no match for his talent, nor his will.

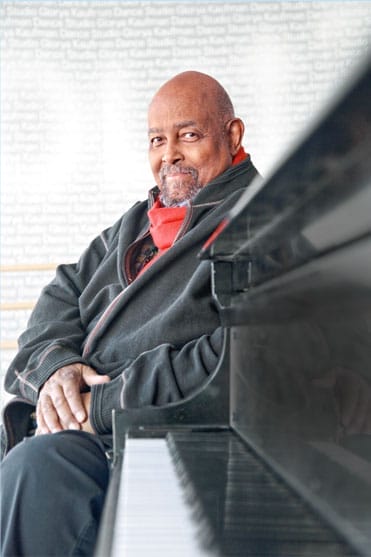

Today, at age 74, DePreist is recognized as one of the world’s most gifted and accomplished conductors. A 2005 recipient of the National Medal of Arts—the nation’s highest honor for artistic excellence—DePreist has appeared with every major American orchestra, as well as those in Amsterdam, Berlin, Budapest, Copenhagen, Helsinki, London, Manchester, Melbourne, Munich, Prague, Rome, Rotterdam, Seoul, Stockholm, Stuttgart, Sydney, Tel Aviv, Tokyo and Vienna. He is widely credited with transforming the Oregon Symphony, his home for 23 years, into a truly world-class orchestra.

He appears regularly at Aspen Music Festival, with the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood and the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Mann Music Center, and currently serves as Director of Conducting and Orchestral Studies at The Juilliard School at New York, where he splits time between tutoring the maestros of tomorrow and sharing his talents with orchestras worldwide (most recently, he served as guest conductor for the Seoul Symphony).

By most any measure, DePreist’s career has been a smashing success. But none of that success, it turns out, came easily. Though he was born into a musical family—his aunt, Marian Anderson, was among the most celebrated contraltos of the 20th century—and though his talents early on caught the eye of none other than the great Leonard Bernstein, DePreist’s climb to the top of the conducting world was, to hear him tell it, a decades-long slog. At more than one point, in fact, he admits he came to believe a career in music would never materialize at all.

In October, DePreist sat down in his Juilliard office for a lengthy interview with Wharton Magazine. Affable, funny and self-deprecating, DePreist over the course of an hour recounted his long, trying trip. He also talked about his remarkable efforts to put the Oregon Symphony on the map, the struggles of orchestras in this tough economic time, his college “friendship” with filmmaker Henry Jaglom and more.

Wharton: How did you end up at Wharton?

DePreist: Well, I lived in Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania was of course a signal institution. I had planned all along to be an attorney, and after talking to some people in my family, they told me, ‘Listen, if you go to Wharton, you’ll not only get a solid business education, but they also have a pre-law minor.’ The program was a little bit more liberal-arts oriented than the other majors at Wharton—I would be able to take courses in the College, too—so it seemed like a perfect fit. Still, there was this contrast between what I was doing at the School, which I thought was really interesting, and the extracurricular activities that I was doing—the concerts I would put on, whether jazz or some other things. So there was always music there, too.

Wharton: How and why did you end up choosing a musical career over a business or law career?

DePreist: I was going to take the LSAT . But one night I was at a fraternity house, and I ran into a person I knew at the time. His name was Henry Jaglom, C’59, and I really didn’t like him. He was coming in as I was going out, and he actually stopped me and said, ‘You really don’t like me much, do you?’ And I said, ‘No.’ He asked, ‘Do you want to talk about it?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ So we sat down and talked. This was about 8 p.m. When we finished, it was 4 in the morning. It was fascinating, just talking with Henry about his plans. He didn’t want to be an English teacher, which is what he was in school for. He wanted to make films. We were both talking about the trajectory that our lives might take, wondering if we’d get the chance to do what we really wanted to do. Well, it turns out that Henry became a very successful filmmaker, and I ended up doing what I did. I think that conversation was the very beginning for me of taking some kind of action on the desire to follow a path in music, rather than being a lawyer.

Wharton: Why even the thought of a career in law?

DePreist: Music was a part of my family—it was a big part of my upbringing. I had piano lessons when I was younger, and timpani lessons, and had taken part in performances with a jazz group and performed in concerts while at Penn at Irvine [Auditorium]. Music had always been there, but not in an organized way—not in a way that seemed that I could do it and make a living. Meanwhile, my godfather John Francis Williams was a very successful lawyer in Philadelphia, and the assumption all along was that I was going to be some kind of professional person—a doctor or a lawyer. But I’m not sure it was ever in my blood. I guess the interest was partly because of a family connection, and partly because there was a ‘plan’ in place for me—you’d go to Wharton, you’d graduate from Wharton, and then you’d go to law school. It seemed right. And indeed, it may have worked. But the fact that I was staying up all night, talking with Henry [about our passions], was fascinating. I should also say that he’s now one of my best friends.

Wharton: How does one launch a career in music?

DePreist: It certainly depends on the situation, but I would say that there has to be more than just a decision. There has to be a commitment that you’re not just going to ‘try’ it, but that you’re going to be ‘committed’ to it—with the understanding that things may not always go super smoothly.

For me, it started when right after Wharton, I went to the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music, where they were having a student competition. This was the same time as when I was at Annenberg [where I got a master’s degree]. When I was there, I was asked to write a ballet score for the Philadelphia Dance Academy. So I wrote that for them and as it turned out I also had to conduct it. The conducting part, I found, was something that I loved just as much if not even more than the composing part. There was something about conducting that was intriguing to me and in some way compelling. At about that same time, I graduated from Annenberg, but because of the classes I was taking at the Conservatory, I got an invitation from the State Department to go on a tour of the Far East as part of one of their special missions.

Wharton: What was the mission all about?

DePreist: It basically involved taking part in lectures about American music, and giving a recital or two. I started in Bangkok, and the mission there was to introduce up-to-date music to the King, who actually had his own jazz band, believe it or not. They would play at the palace every Saturday, and the performances were broadcast around the country. Well, they had these old 1940s stock arrangements—kind of staid—and the band was good but not great, so some of the arrangements were just beyond them. But I eventually found out that in Thailand there were these fantastic Filipino musicians who were playing the night clubs. We gathered them up—or, somehow, they found me—and we got together on Saturday at one of the local universities. We would have these reading sessions, and I’ll tell you, these guys were phenomenal. I started asking those guys, ‘Is there a symphony orchestra here?’ One of my friends eventually said there was, and he asked me, ‘Why don’t you swing by sometime for rehearsal?’ This was the first time that I was actually in the presence of a symphony orchestra, and after a while they asked me if I would like to conduct a part of a performance they were working on. When I did that—when I had my first chance to conduct an orchestra in the symphonic repertoire—I realized, ‘Wow, this is a whole different kettle of fish.’ And I’ll tell you, when I got on that podium, it felt as natural to me as anything I had ever done in my life. I said, ‘This is it.’

Wharton: But then just as you had this breakthrough, you got sick, correct?

DePreist: Yes, at approximately the same time, I contracted polio. I didn’t know it was polio. I just knew I couldn’t stand up. All I was concerned about was getting out of the hospital so I could get to the next rehearsal. But I kept getting these bureaucratic messages as to why I couldn’t [get out of the hospital]. I wanted to get home as soon as possible to begin therapy, you see, but I was just laying there in that hospital bed. Eventually I asked somebody on the staff at the U.S. Embassy if they would send a telegram to my Aunt Marian [Anderson], who was just on the front page of the International Herald Tribune, pictured walking with Bobby Kennedy. Now this was before email, so the telegram said: ‘Eager to get home to begin therapy. Is there anything RFK or JFK can do to get me out of here?’ Well, I figured that even if that note wasn’t helpful, it would at least make clear just how desperate I was. But the secretary from the Embassy came back and said, ‘Jimmy, we think this is going to cause more problems than it’s worth.’ So finally I found a friend and asked him, ‘Will you please make sure this thing gets sent?’ Long story short, I heard almost immediately that there was going to be a plane.

Wharton: What do you remember about the trip home?

DePreist: We were loaded up on this hospital plane, and there were stretchers [stacked one on top of the other]. The space between my head and the stretcher above me was maybe six inches, and it was very claustrophobic. But I remember very clearly that directly in front of me there was this marine, and he had a very serious gunshot wound to his abdomen. He was not supposed to drink any water. But he was thirsty, and he was really in agony. By comparison, I knew my problem was nothing. And I remember thinking, ‘There’s a lesson here.’ It was a teachable moment. I’d been blessed my whole life, and I figured that I should be able to handle this. Eventually we landed at an Air Force base in California, and as they were unloading us, I saw that these were all guys who had been wounded in Vietnam. Some of them had serious, serious wounds, and the worst off was that poor Marine. So that night, I’m in my bed, and between my room and the next room there was a bathroom. At some point I hear water running, and I assume, just because of the karma spinning around, that it must have been the Marine, trying to drink water. So I told the corps man who was on duty, ‘I want you to go check in that bathroom.’ Turns out it’s the Marine, and the guy is just about passed out. They have to work on him, get him back in the bed, and manacle him down so he won’t get up. All night, you heard this straining on the bed. I felt so sorry for him.

Well, the next morning, the door opens and the nurse says, ‘The Marine would like to say something to you.’ The Marine said, ‘Could you come over here? I’d like to thank you.’ But of course, I couldn’t. That was the first time I had to tell somebody I couldn’t walk. It was a reality check.

Wharton: How, then, did you go about launching your career, despite your new disability?

DePreist: I finally got back to Philadelphia, and I didn’t know what was going to happen. I wasn’t even thinking about a career in conducting. I was just dealing with this impediment. At the same time, there was no frame of reference for anyone having a conducting career with this kind of disability. So at one point I wrote to Leonard Bernstein, and told him about my problem, and he said, ‘That’s horrible, but if you want to give conducting a shot, you should still do it.’ He suggested I enter the Dimitris Mitropoulos International Conducting Competition, which was the most prestigious competition in the world at that time.

Eventually I get up there, and when I finally got the chance to conduct, I had forgotten how much I loved it. Hearing those sounds—it was really wonderful stuff. I was just so thrilled that all of the sounds in my head were exactly the same sounds that were coming out of the orchestra. I reached the semifinals that year, and soon after a letter came from Lenny [Bernstein], saying how impressed he and the judges were. They thought I had a very bright future. That was enough to keep me going.

Wharton: What was your next step? Did the competition gain you any opportunities?

DePreist: I actually had an invitation to return to Bangkok. Some people wondered if I’d even accept, but I did accept, went back and worked with several orchestras over there. I eventually returned to the United States, entered the Mitropoulos competition again and won first prize. Then I served as Bernstein’s assistant for the 1965-1966 season, with the New York Philharmonic. And then of course you figure, ‘Well, that’s it, right? The career is on its way.’ But you know what? There was no interest from anybody in me. ‘Oh, you won first prize in the Mitropoulos? You served as Bernstein’s assistant? Oh, well, great.’ It just didn’t mean anything to anybody. … I was convinced the conducting business did not need me. There was a wonderful review of one of my concerts in The New York Times. I had a letter of recommendation from Lenny. And after all of that, only one person wrote back. She was a big manager in Holland, and she said, ‘Even though you’re a complete unknown here, if you’re ever in Holland, please stop and see me.’ Well, it turns out that while I was with the Philharmonic, I came to know Edo de Waart, who was from Holland and also a prize winner. He was the only person I knew in Holland, and because Antal Doráti, whom I also knew from the competition, was in Stockholm, I decided I would move to Europe and starve slowly, rather than rapidly in New York.

So I went to Rotterdam. It was just phenomenal, if a little bittersweet. Because while you’re happy for your friend Edo—he has this great orchestra, 105 pieces, and even though he was the second conductor, he had this huge dressing room—you’re also wondering, ‘Why not me?’ But it turned out that Edo had spoken to his manager about possibly giving me a chance. And it ended up being quite a serious concert—not light in any sense. I did Stravinsky, and Schubert, and Dvorvák. Of course, your hope when you do one of these things is not just that the reviews are good, but overwhelmingly good. And they were. It was spectacularly successful—with the critics, with the orchestra, with everyone. That was really the beginning of things for me.

Wharton: Jumping ahead a bit, then, how did you eventually start your career back here in the States?

DePreist: Doráti became the music director at the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, DC, and this was in the last year that the National Symphony was at Constitution Hall, which was the very place that my Aunt Marian was denied the chance of singing [because she was African-American]. I remember calling her after I went to DC, telling her, ‘I cannot believe there was a time when you just couldn’t come here and work.’ And she said—this was very much Aunt Marian—‘Times have changed, and I’m happy for that.’ Then the symphony moved to the Kennedy Center, and that was the start of really active work for me, as Doráti’s assistant. Soon after, I was offered the chance to take over Quebec’s orchestra, which was looking for a music director. It was a stimulating time, and I loved it. From there, I was also asked to guest conduct in Portland.

Wharton: You have been widely credited with helping put the Oregon Symphony on the map—of making it into a truly world-class orchestra. How did you pull that off?

DePreist: It was about being in the right place at the right time. When I got there, they were a part-time orchestra. They were rehearsing in the evenings so their musicians could have day jobs, because they simply couldn’t afford to pay them full-time salaries. So the first thing we needed to do was identify how we could take the next step and also to have the musicians play full time, which meant they had to make a decision about whether they wanted to keep their day jobs or not. And at the same time, the management needed to make the commitment to pay them decent wages. Well, this was all a big issue as you might imagine. But that was my job—to make it happen—because I felt it was important. We moved over into a new theater, and started paying musicians a decent wage—it was still a pittance, really, but at least it was a decent salary. The orchestra started to get better and better, and we started inviting better guest conductors to come and spend some time there. And there were also some people in the community who had the money to make this all work. It was just a perfect time to make the move. We started to do recordings, and people actually started to notice that, yes, we had an orchestra in Portland.

Wharton: You mentioned that a key factor in your success at Portland was the fact that you had the support from the community—and donors. Given the state of the economy today, and given the news of many orchestras facing serious financial trouble, would it be fair to say that classical music is in “crisis” right now?

DePreist: People have always said it’s in crisis. ‘Oh, those orchestras—they’re of the past.’ The reality is that relatively few have actually gone out of business. But at the same time, nobody has come up—and this is one area where my Wharton background comes back—with a system by which orchestras can have sustainable financial support from commercial entertainment, where they can generate funds by putting on what you might call ‘popular concerts.’ They have to be able to do something beyond just relying on their traditional concerts to bring in people, because the reality is that the old idea of philanthropy that was such a part of the generation before is over. I’m not saying it was always super easy, but it was easier to get those people to give back because they understood. Today, obviously, everything costs much more, and musicians also expect much more. I read recently that musicians in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra had scheduled a strike because they felt their $106,000 base pay was in jeopardy. Now, I am always supportive of musicians, but in the court of public opinion, that seems a bit absurd.

There are certainly problems. I am music advisor for the Pasadena Symphony, and in Pasadena you have a community that in the past had generated considerable funds. But now, this wonderful orchestra in this beautiful place is struggling. And they aren’t alone. I think it’s the marginal orchestras in those marginal communities that are in trouble. It’s a difficult time.

Wharton: You are still actively conducting, and you serve in many other roles, too. So how did you end up at Juilliard?

DePreist: After 23 years at Oregon, I knew that there had to be something else that I could do. And around that time I had been approached by the president at Juilliard, who asked me to think about maybe coming here to teach and do some concerts. I told him, ‘You know, I’m really not yet ready to leave that active arena.’ And he said, ‘OK, I’ll wait.’ I eventually decided that it was the right time to do it, and I must admit, I had no idea that I’d enjoy it as much as I do. It’s the absolute perfect job for me right now. I have independence. I can do concerts at Carnegie Hall and elsewhere. And I have independence in my selection of conducting students, and helping them shape their course of study. It has been wonderful.

Wharton: Last question: What’s next for you?

DePreist: I would like to stay at Juilliard as long as they’ll have me, and I’d hope to try and remain helpful elsewhere if there are any orchestras out there who need me—orchestras who need advice on how to avoid the pitfalls that have been there for other orchestras. But of course, conductors don’t really retire. They just morph into some other role, or they continue to conduct, but in a different place. The amount of enrichment I get when I conduct—that’s too valuable of a feeling to give up. That’s why Juilliard is so wonderful right now. I can give back to the music world by teaching, and also reward myself with the concerts I get to do.