On a bright morning in 1989, James Martin, W’82, was kneeling in a puddle on the broken-tile floor of a communal bathroom, part of a hospice run by the Missionaries of Charity, the religious order founded by Mother Teresa. The sisters, clad in blue-and-white saris, often carried back those who would otherwise die on the streets and garbage heaps of a surrounding slum in Kingston, Jamaica. Martin hefted the sad and silent man he’d just showered and dressed him. There were still a dozen dying men who needed to be washed, shaved, dressed, and have their nails clipped.

When Martin told friends that, after four years at Wharton and six years moving up General Electric’s corporate ladder, he was about to leave it all behind to become a Jesuit priest, their responses were pretty much the same: “You’re kidding, right?” Bobby, a boy from a Lower East Side school where Martin later taught for a while, made the same point but without the incredulity. “Man,” he told him, “you’re crazy!”

Today, Father Martin works out of a Manhattan office building. In 1999, he was ordained a Catholic priest and is now doing a stint as associate editor for the Jesuit’s national magazine, America. On weekends, he celebrates Mass, preaches, hears confessions, and runs book clubs and parish retreats at St. Ignatius Loyola Church on Park Avenue.

“I love being a priest,” he says. “It’s a gift and a joy.” As a priest, he finds himself being invited into people’s lives in surprisingly intimate ways. “The collar predisposes them to trust in you… and they’ll talk about the big topics – death, birth, marriage, confession. It’s incredible to be able to accompany people in that way.”

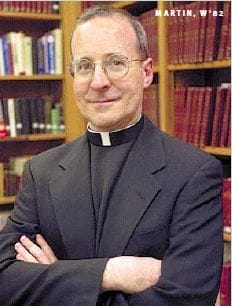

Martin is a fine-featured and gentle man, but he retains a businessman’s earthiness in some of his expressions. He has on a black suit and shoes, and a black clerical shirt with a little square of Roman-collar white at his throat. Once in a while, he’ll be startled on the street, catching a glimpse of his white-on-black image in a shop window. “Wow!” he says. “I’m a priest. How’d that happen?”

A finance major with extensive training in accounting, Martin became an intern in GE’s Financial Management Program and eventually moved from international finance to human resources with GE Capital. “When I started, it was the fulfillment of all the dreams I had at Wharton, which were to get a good job at a high-powered company, to make a good salary, and to have unlimited opportunity for advancement.”

It took six years of hard work and promotions for Martin to understand that the dream of success was, for him, far sweeter than its fulfillment. By that time, he was working most weekends, and as an HR manager, he had become disillusioned by what he saw behind closed doors. It was the era of Jack Welch’s ambitious quest to generate spectacular profits by making GE “lean and mean.” It was also the era of Reaganomics, and the tough corporate culture that trickled down from the top was not congenial to him. “It was all about the bottom line,” he remembers. If you failed to make your numbers, you were out. In time, his ample bank account could no longer compensate for the migraines, stomach troubles, and depression. “I couldn’t figure out the point of what I was doing with my life,” he wrote in his memoir, In Good Company. “Something basic was missing.”

That “something,” he soon discovered with a slight shock, was religion. All along, he’d been reading in secret about the religious life, but it wasn’t until he’d become completely miserable at GE that he was able to feel a deeper attraction to the “holiness” and “peace” the Jesuits seemed to offer. It was a romantic notion, he admits – sort of an infatuation – but “that was the call.”

New Jesuits undergo a rigorous, ten-year program of preparation, which includes prayer, philosophy, and theology studies and some kind of work, often a social-service ministry. Before being ordained, Martin spent two years (1992-94) with the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) in Nairobi, which helped care for Kenya’s three million displaced people, who were fleeing the grinding cycle of wars and famines that afflict east Africa. “[N]othing was as I expected it,” he wrote in This Our Exile, the story of his experiences there. “And my life changed totally.”

Uprooted from their homes with little more than the clothes they wore, up to 100,000 refugees lived in the squalid slums on the outskirts of Kenya’s capital city. “The sight of women standing in long snaking lines waiting for water and men wearing tattered clothes picking through garbage dumps was profoundly sorrowful,” he wrote.

Many of the refugees came from their homelands with marketable skills, and JRS offered grants to help individuals and groups start up businesses that would make them self-sufficient. The refugees invested the $1,000 in seed money (a substantial sum) for material and equipment for dress-making businesses, bakeries, restaurants, basket weaving and other craft projects, small dairy or chicken farms, hairdressing salons, and other ventures. Martin took over the program and founded the Mikono Centre, which consisted of a shop that sold refugee crafts and wares, and an office with a wooden chair and desk, where he disbursed the grants and brainstormed over business ideas.

About half of the new undertakings failed. The refugees toiled doggedly at their enterprises, but many succumbed to illness or violence or another of the plenitude of misfortunes that plagued their tenuous existence. Martin was delighted when businesses prospered, which meant the owners’ families had enough to eat and a roof over their heads. “I had to rejigger my notions of what success and failure are,” he explains. “I had to trust that God would somehow use [my] efforts to succeed and flower in some place I might not see.”

For those who failed, he stayed in touch, offering encouragement, counsel, some prayer, and sometimes a little cash. Some of the refugees still write and mail pictures, and he still sends along some money in his replies. “In the end,” he says, “it was all about being with them.”

By the time the World Trade towers were swept away on September 11, Martin was already a priest and working at America magazine in Manhattan. The attack laid bare the refugee status – the fragility and danger, the impermanence and departure, the pain and death – that underlies the human condition, even in the Wall Street district. For several weeks after 9/11, he went downtown to accompany police, firefighters, ironworkers, and rescue teams in their grim tasks. His most recent book, Searching for God at Ground Zero, chronicles what he witnessed.

By the time the World Trade towers were swept away on September 11, Martin was already a priest and working at America magazine in Manhattan. The attack laid bare the refugee status – the fragility and danger, the impermanence and departure, the pain and death – that underlies the human condition, even in the Wall Street district. For several weeks after 9/11, he went downtown to accompany police, firefighters, ironworkers, and rescue teams in their grim tasks. His most recent book, Searching for God at Ground Zero, chronicles what he witnessed.

Mostly he just listened to volunteers telling their stories, feeling their feelings, and grappling with the big questions the experience raised for them. His clerical collar was an invitation for them to open up or to ask for a blessing, but just as often he found the volunteers solicitous of what he too must have been going through. He celebrated an outdoor Mass there with a group of weary, ash-covered workers. “It was once again an experience of knowing that I was somehow in the right place at the right time,” he says.

The “somehow” of Father Martin’s priestly vocation haunts him when he thinks about it. Somehow he set out on a lifetime career in business and ended up a priest – almost despite himself. “Divine Providence,” the theologians call it. “If I had tried to design a perfect background to work at the Mikono Centre,” he observes, “I could not have done as well as I did by accident.”

Peter Nichols, CGS’93, is editor of Penn Arts & Sciences.