Asingle shout sounded from down below on the cellblock, then a chorus of hollering. The noise filtered through a metal door at SCI Chester medium-security state prison, where two Wharton MBAs sat in a classroom setting with five men in maroon prison uniforms. If this had been a movie, the sudden cacophony might have been the first hint of trouble. But neither the MBA-candidate volunteers nor the incarcerated learners flinched.

A Chester learner stood front and center, detailing his plans to run a mechanic shop post-release. Each of the five incarcerated men would describe such a personal financial plan. They professed feeling nervous but delivered smooth, comprehensive presentations — a chorus of mastered details.

“I’ll have about $3,614 when I get out,” said one. “I’m budgeting $950 for rent in that neighborhood. For utilities and phone, I’m budgeting $250…I’ve been promised a job making $22.50 an hour, giving me an income, after taxes, of about $2,200 per month.” Then there would be clothes, food, and transportation, he noted, along with any restitution, fines, and fees owed.

The MBAs listened and offered probing questions. “How certain is this job your friend is promising you?” one asked. “It’s certain. I mean, he told me I’ve got it. Immediately.”

“And what’s your path to promotion?” Each man’s presentation started as a budget but took flight as something else: a narrative, lifting him to a peaceful, productive, stable life.

The clamor down below sparked up occasionally but soon lost any sense of mystery: The raised voices came from a crew setting up for a concert that night in the prison. Their occasional hollers were jovial, inadvertently fueling the sense of celebration inside the classroom during this, the last session of a financial class brought to SCI Chester by Resilience Education | Wharton WORKS, a landmark program at the Wharton School and one of only a few among business schools nationally.

“Their presentations were really strong,” says Andrew Ren WG24, one of the MBA candidates who taught the group. “But I can’t say that I was surprised. By this time, we know them and they know us, and they’ve really engaged with the material.”

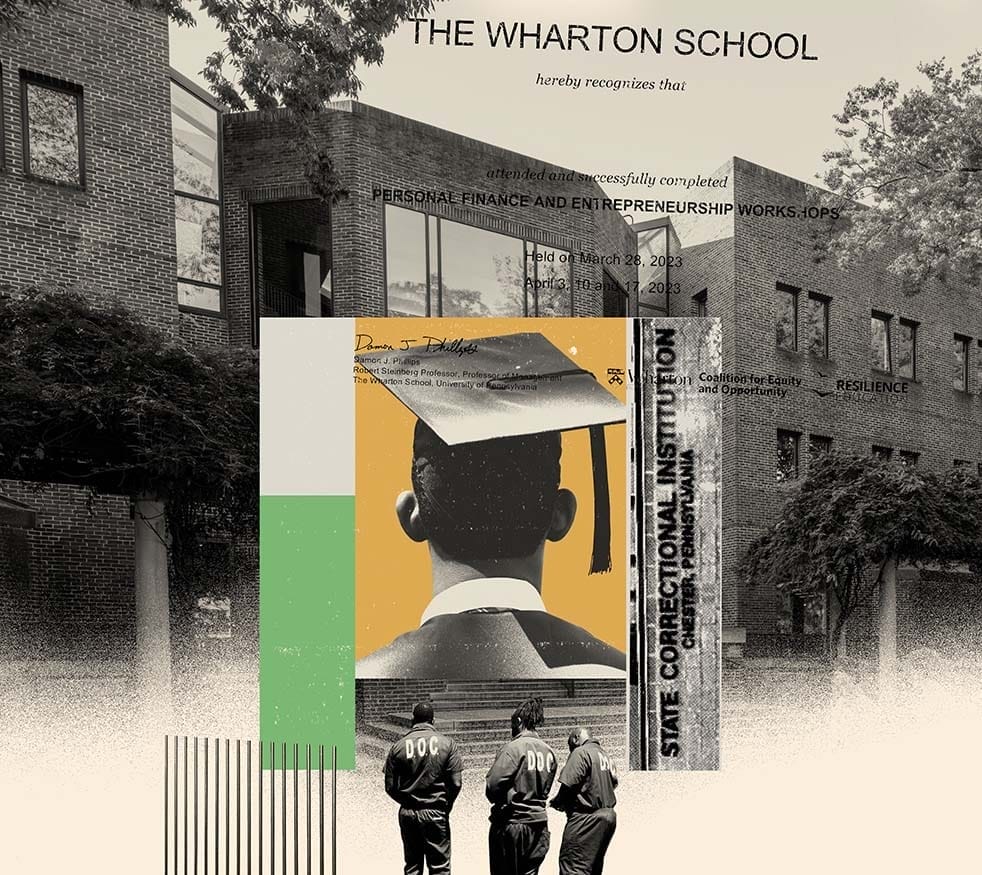

The workshops, run by Wharton management professor Damon Phillips, take the form of a two-session series covering personal finances and entrepreneurship. Wharton WORKS (Wharton Opportunities for Reentry, Knowledge, and Skills), in partnership with Resilience Education, is the flagship program of the Coalition for Equity and Opportunity (CEO), one of the School’s six research pillars. WORKS fits neatly into CEO’s threefold mission: to equip present and future leaders with the skills needed to create equitable organizations, drive positive outcomes in business, and foster wealth-creation opportunities.

WORKS also offers post-release professional mentoring for people reentering society from prison, whether they took the business classes inside or not. MBA-candidate volunteers serve as professional mentors and teach inside SCI Chester, and each fall and spring session ends with a graduation ceremony. WORKS learners receive a casebook that covers the same ground as any early business course, including accounting principles, budget preparation, and more.

Like the budgets the incarcerated learners prepare, Wharton WORKS also takes flight as a narrative, showing how the business community at large and Wharton in particular can take the lead on a difficult and overdue task: reshaping our longstanding views of incarcerated people from figures to fear — their voices abstract and cause for alarm — to people with skills to share and the same dreams as the rest of us.

As a teenager, Damon Phillips worked at his father’s fiber-optics business in Florida, sometimes finding himself alongside co-workers with criminal records. “The experience planted a seed in me,” says Phillips, “because I couldn’t help but notice that these people were often some of the best employees.”

Formerly incarcerated people typically suffer dispiriting unemployment rates. A 2021 Bureau of Justice Statistics report tracked more than 50,000 individuals released from federal prison in 2010 for four years and found that 60 percent were unemployed at any given time, while a third found no work at all.

At his dad’s business, Phillips saw that most such people attacked the work, bringing their best effort every day. But his path from this observation to Wharton WORKS proved circuitous, winding from STEM studies to a stint as a U.S. Air Force engineer before he earned a Stanford PhD in business. In 2015, he became co-director of the Tamer Center for Social Enterprise at Columbia Business School, helping oversee civic-minded initiatives. Conversations there led to a partnership with Darden University professor Greg Fairchild and his wife, Tierney Fairchild C89, who started teaching finance and business management classes in the area’s prisons through a partnership with Resilience Education. Capitalizing on the lessons he first learned on his father’s shop floor, Phillips established a new outpost for the program at Columbia.

Phillips arrived at Wharton in 2021 and launched WORKS, which kicked off last spring and now sits as a crown jewel in Wharton’s efforts to further positive societal outcomes. CEO’s goal of enhancing wealth-building opportunities across racial, gender, religious, and socioeconomic lines, says faculty director Ken Shropshire, makes Phillips a perfect fit.

“I was very happy when I heard he was coming here,” says Shropshire, who’s also professor emeritus of legal studies and business ethics and senior advisor to the dean. “This kind of novel effort to serve the community is exactly what we’re about.”

In April, the general public was given a look at Wharton WORKS programming and research through its new Business Case for Second Chance Employment Conference. Co-chaired by JPMorgan Chase and Eaton Corporation, it’s another important step for the program. “People don’t necessarily put the Wharton School and prisons in the same sentence,” says Fareeda Griffith, managing director of CEO. “But within CEO, our focus is on the wealth gap, which affects people’s overall health and opportunities. We’re doing the empirical work, but we’re also creating programs, like WORKS, to provide skills and tools to alleviate that gap.”

The program isn’t just for the incarcerated. “The learning is a two-way street,” says Tierney Fairchild, Resilience Education’s co-founder and executive director. “The incarcerated learners learn from the MBA students, and the MBAs learn from them, too.”

This might sound surprising: What can MBAs learn from people in prison?

For one thing, says Phillips, they might learn about a valuable hiring pool. After all, Wharton MBA candidates re-enter corporate management roles, with the power to influence and set policies, hire, and fire. The hope is that they’ll put what they learn at Resilience Education | Wharton WORKS into action. The program features ambitious goals in this regard: to help 3,000 formerly incarcerated people get living wages and career-track jobs, and to assist another 300 in starting businesses by 2030.

Accomplishing this wouldn’t just be a matter of professional pride for the MBAs, says Phillips. It would be a personal one, too — something he points out to his MBA volunteers before they enter SCI Chester. A lot of the conversation, he informed a group of volunteers at a recent winter training session, had revolved around their role as educators. “But you should be aware,” he told them, “this experience is also going to be transformational for you.”

All of the MBAs who volunteer with Wharton WORKS as instructors or post-release mentors must first take Phillips’s immersion course, Reforming Mass Incarceration and the Role of Business. The title is an unusual one among Wharton’s offerings but is welcomed by some business students left cold by the old “Just serve the shareholder” philosophy.

“I came to school here already very interested in the relationship between business owners and all stakeholders of society,” says Sushmita Mukherjee WG24. “And to find this class where we could take our learnings in business, in a very practical way, and share them with a population in society that is normally not reached was very powerful to me.”

The curriculum illuminates the contours of America’s justice system: The U.S. comprises just five percent of the world’s population but makes up 25 percent of the global prison population. Our system imprisons racial minorities at far higher rates, typically for nonviolent offenses, leading to charges of a New Jim Crow in America’s prisons. Massive amounts of money change hands — $80 billion annually for prison costs alone. The more than 600,000 people released from U.S. prisons each year face chronic unemployment. And numerous studies have shown that stable employment reduces rates of recidivism.

Just this past year, Iowa, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Tennessee boasted of drastic recidivism reductions, crediting increased re-entry, rehabilitative, and jobs programs for the improvements. The Virginia Department of Corrections released statistics showing that recidivism rates for people who’d taken career and technical education programs while incarcerated fell to 12 percent.

Phillips teaches in part from a seminal 2020 paper he co-wrote. Among its findings: Driven by unemployment or low-paying jobs, formerly incarcerated people start their own businesses at rates five percent higher than the general population. The discovery raised a tantalizing question: Since formerly incarcerated people had the financial and managerial acumen to start their own successful businesses, why not hire them? Data like this suggests that Wharton WORKS will, well, work. But from here, the learning gets less academic and more personal.

At the program’s midpoint, MBAs confront a simulation offered online, and sometimes in person, that places them in the role of someone just released from jail. The sim was designed with input from Phillips and in concert with numerous formerly incarcerated people, who took him through the experience in granular detail. MBA students are given a small financial budget to accomplish the necessary tasks: Make visits to parole officers and counselors; take and pay for drug tests; obtain identification and personal records; find a job and a place to sleep; pay for food, clothes, and public transportation. Time works against them; a two-minute transaction in the game takes hours in “sim” time, just as it would in real life.

MBA candidates say the sim is infuriatingly difficult, not least because it includes real-life randomness. The line at the job center looks relatively short — perhaps 75 minutes when you arrive in the morning — but if you get there late, it lengthens like a horror-movie hallway, to four hours or more. The clerks depended on for information and assistance may be respectful and professional, curt and dismissive, or downright hostile. If you’re still in line when the center closes, you’ll need to come back during the simulated tomorrow.

“I think it was the most powerful thing I did,” says Mukherjee. “It just made it very real for me that we do not set these people up to succeed. We set them up to fail.”

All the while, as time, money, and options dwindle, MBAs can visit the “take a risk” station, which means committing some petty crime for necessary dollars. Anyone who’s seen Les Misérables feels empathy for its central protagonist, Jean Valjean, who must steal to eat. Phillips’s sim puts these relatively well-off MBA candidates in Valjean’s shoes.

“The sim was very powerful,” says John Burgoyne WG24, “because it felt impossible to do. Taking a risk felt very reasonable.”

“You can see their frustration building,” says Phillips. “I tell them: You experienced this for just a few hours. Imagine if this was your life.”

Wharton volunteers cite a particular moment of impact on entering SCI Chester. “That first time you go in,” says Andrew Ren, “and the sally port closes behind you, it hits you.” A corrections officer sits inside a wide glass booth and eyes passersby, who must hold up small wrist bracelets to demonstrate that they’re approved visitors. The officer buzzes them in and out, enforcing a grim reality. As Ren notes, “There’s no leaving without him.”

As “dual learning” models go, this one creates an immediate impression. “You see them when they enter the facility for the first time, looking nervous,” says Phillips. “And the first 15 minutes they’re teaching, you see it. It’s normal to feel nervous at first. Then you add onto it that you’re in a facility like this for the first time.”

But a sense of safety, even comfort, eventually dawns. Ambient noises, like those shouts on the cellblock, no longer cause concern. “There’s a level of trust that develops,” says Ren. “Part of it is that we know we have these incarcerated learners with us who will look out for us.”

The classroom sits upstairs along a prison catwalk — an unusual spot for higher education. But the instruction itself is standard for many business schools: Learners are given written case studies to read before class, part of that foundational casebook.

The magic is in the method. The classroom, comprised of long tables arranged in a U-shape, is something like a corporate boardroom. Colleagues face each other to hash out shared problems, using the Socratic method. The MBA instructor starts with the first probing question, but the conversation flows as students offer answers and ask questions of their own.

“It’s all about conversation, a sharing of ideas,” says Phillips. “Nothing anyone says can be wrong, because the conversation builds on itself. The next person talks and folds what was just said into the larger conversation.”

When it’s done right, lines of authority shift, blur, and disappear. For the incarcerated, the learning comes not only from the information they’re taking in, but from the experience. The MBA candidates and incarcerated learners address each other with honorifics before names: “Mr.” and “Ms.”

“For most of these men and women we’ve taught over the years,” says Tierney Fairchild, “this might be the only time during the day or week where anyone asks them what they think — and where what they think matters.”

Listening to incarcerated people talk about post-release plans during their budget presentations also helps make them relatable to the MBAs, says Bianca Bellino, Resilience Education’s national program director. “It’s good to hear what their re-entry plan is and that they have a job secured or a prospect,” she says. “Or how they’re budgeting, like, ‘I want to take a mini vacation with my family, because I haven’t seen them in 10 years.’”

Allison Kroboth is a success story that Wharton WORKS hopes to emulate. She took the personal and business management courses in Virginia through Resilience Education and earned employment in Philadelphia after her release. She now works as a software engineer and grant writer. Kroboth credits the Resilience program with changing the course of her life in both practical and psychological terms.

“I think that of everything that happened to me, this program made the biggest difference,” she says. “The education, and the experience of it, of being able to sit and talk with these MBAs, changed how I saw myself.”

It was the Socratic teaching method that led to Kroboth’s transformation — a standard practice of business schools leveraged to create dramatic personal change. But that change reflected something deeper: a “very intentional” effort, says Phillips, to harness the power of one of his old STEM interests, the placebo effect.

For decades, scientists acknowledged the effect’s existence but never sought to answer why. Phillips’s paper, published in 2015, drew from then-new science that answered the question: Patients, experiments testing the effect determined, respond to a variety of social and experiential factors, like the color of the doctor’s lab coat, information about a pill’s efficacy, and much more, all of which contribute to their belief in the treatment and their ultimate outcome. “The placebo effect,” says Phillips, “is powered by all these social and cultural constructs. And it has both mental and physical effects that we can measure.”

His paper suggested that the placebo effect’s power could be harnessed intentionally to create positive change. Resilience Education | Wharton WORKS does exactly that, dropping MBA candidates and people doing prison time into the same room to talk business — and also to see and understand themselves differently.

“I already understood that I was very privileged,” says Burgoyne, citing that as one reason he took the class. “I was interested in coming to Wharton to see how business could be a force for good. But this entire experience was more powerful than I even expected in terms of resetting how I see myself and the people I was teaching.”

Burgoyne is shaping the next steps of his career around what he’s learned: He’s continuing an independent study he began with Phillips, adapting a Johns Hopkins program to hire formerly incarcerated people for Penn. And he’s taking a job with REDF, a California-based venture philanthropy firm, to work on initiatives to help the formerly incarcerated overcome hurdles to employment.

Mukherjee shares a similar experience: “I watched these people, over the length of the course, grow and share more of themselves because of the environment we created in the classroom. And I recognize now that my role in management is to believe that the people I’m managing can crush it and set up the environment for them to be at their best.”

SCI Chester wouldn’t allow any of the facility’s incarcerated learners to be interviewed or identified. But during the final personal finance workshop last December, the effect of the program could be seen in the ease with which conversation flowed.

“I’m thinking,” one older man suggested, “of trying to find a job I might want, then going to that business and saying, ‘I will work for free, initially, for some period of time.’” He had acquired multiple job qualifications while serving his time and wanted to provide a potential employer with evidence of his work, professionalism, and commitment to overcoming the stigma of his prison sentence.

Ren listened and then gently offered some advice: “I would be leery of giving your work away. Don’t sell yourself short.”

“Well, I have to tell you,” the incarcerated man responded with confidence. “I also think of that time as my chance to kind of interview them. And to determine, do I want to work for this person?”

Ren broke into a wide smile, then made a carefully considered reply: Perhaps he should instead seek a contractor-type relationship with a prospective employer, allowing them both to get to know each other while also ensuring he got paid.

Laid bare, the subtext of their exchange is powerful: The incarcerated man told Ren his sense of self-worth was greater than one might expect, and Ren essentially responded, “Good — but you’re worth even more than that.”

When the conversation ended, the air between the MBA candidate and the learner was like that of friends who were feeding off each other’s ideas to reach a better outcome than they might have found on their own.

Minutes later, the Resilience Education | Wharton WORKS volunteers handed out certificates proving that each of the participants had completed the program. The sense of accomplishment appeared shared among both the incarcerated learners and the MBA candidates. They passed the next several minutes standing in a semicircle, shaking hands and chatting amiably, like co-workers at a watercooler. Maybe one day, some of them will be exactly that.

Steve Volk is an investigative solutions reporter and Stoneleigh Fellow with Resolve Philly, covering the foster-care system.

Published as “Teaching Finance, Transforming Lives” in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Wharton Magazine.