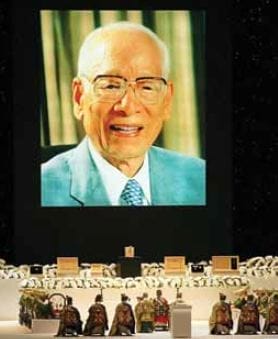

Not long ago, I attended the funeral of Momofuku Ando, the inventor of instant ramen. On the playing field of a domed Osaka baseball stadium, 6,000 people sat facing the homerun wall, where rows of Buddhist monks framed a long white stage. The stadium was pitch dark, save bluish LEDs that twinkled in the bleachers and galaxies that rotated on video displays in the upper deck. The outer-space theme was an homage to Space Ram—a zero-gravity instant noodle that Ando’s company, Nissin Food Products, developed for astronauts — but also a tribute to Halley’s Comet. Ando was born in 1910, the year the comet made one of its near-Earth flybys, and the implication was that both he and instant ramen came from above.

The funeral included speeches by former prime ministers and chanting by the monks, but there were also goodie bags. Each attendee received a five pack of Chikin Ramen, a container of the newly introduced “Eco” Cup Noodles (with a reusable plastic cup), and a book of Ando’s famous sayings. Some of these sayings were about golf (“Eighteen holes is the only happiness money can buy”) and food (“Meat goes with potatoes for a reason”), and some were simply bizarre (“Mankind is noodlekind”).

But many were about management and innovation, each relating to an episode in Ando’s remarkable entrepreneurial career.

“When you see people waiting in line, stop to investigate. In a line, you can discover the desires of the masses.”

The day after World War II ended, Ando walked the streets of Osaka. Ando’s aircraft parts factory had been destroyed, as were several office buildings he owned. While thinking about what to do next, he noticed a black market for food had sprouted up behind Umeda Station, a transportation hub. There, he came face to face with his destiny: “I happened to pass this area,” he once wrote, “and saw a line 20 or 30 meters long in front of a dimly lit stall. I asked a person who was with me what all the fuss was about, and I was told that the stall sold bowls of ramen noodle soup. I thought, ‘People are willing to go through this much suffering for a bowl of ramen?’”

“Perspiration might lead to inspiration, but only if you set clear goals.”

It took Ando more than 10 years to act on what he discovered. When he did, at age 47, he built a wooden shack in his backyard, filled it with cooking equipment, and spent most of 1957 and part of 1958 inside. He pursued five goals. The noodles had to be: 1. tasty; 2. capable of keeping for a long time; 3. ready in three minutes or less; 4. economical; and 5. healthy and safe. He repeatedly steamed noodles, dried them, and poured hot water over them. But this produced only one failure after another. His eureka moment came while watching his wife prepare a batch of tempura in boiling hot oil. When he dipped his noodles into the same hot oil, Ando found that frying not only dried them, but also left the noodles with small holes that made them highly absorbent.

“Let them eat it with forks!”

In 1966, Ando traveled to the United States to promote instant ramen. At the Los Angeles supermarket chain Holiday Magic, he watched in stunned silence as American executives placed his noodles in Styrofoam coffee cups (not bowls!). After filling the cups with boiling water, they ate the noodles with forks (not chopsticks!). Where others might have lectured the execs on how to consume the product “properly,” Ando saw the opportunity for a revolutionary new packaging design. Five years later, Nissin launched Cup Noodles, its first international megahit.

Today, the company Ando created employs more than 21,000 people in 11 countries. Its net sales are more than $3 billion a year.

After the funeral, I left the stadium and rode a train to the Osaka suburbs, where I toured the unexpectedly chic Instant Ramen Invention Museum. Ando built it himself, to encourage young people to become entrepreneurs.

One thing I had long wondered about was why a 47-year-old man would suddenly build a shack in his backyard and spend a year in it trying to invent instant noodles. A book for sale in the gift shop told the story.

Ando had been the head of a bank that made many bad loans. Depositors came after him to recoup their losses. At first, he thought he might die of poverty. Or shame. But as he sat alone with his failure, he remembered the line for ramen. And he understood—in what reads like some kind of spiritual transformation—that noodles were his true destiny. Still, he never disowned his previous experience.

“I came to understand that all of my failure—all of my shame—was like muscle added to body.”

These days, with failure seemingly all around us, I think of these words often.

Andy Raskin, WG’94, is the author of The Ramen King and I: How the Inventor of Instant Noodles Fixed My Love Life, a memoir.