Jill Le Grand G96 WG96 had never set foot outside the United States the first time she moved to Paris, in 1990. The 24-year-old New Jersey native didn’t speak French; she didn’t have a job in the city, or a place to live. What she did have was a vision: She knew she wanted to develop a global career — a global lifestyle, really. She also knew that was unlikely if she stayed in her job as a financial analyst in New York. So she got on a plane and relocated overseas.

French Immersion class with Jill Le Grand G96 WG96 (third from right), 1994

In Paris, Le Grand spent a handful of years in finance-focused roles — first with a nonprofit, then with KPMG, then with Goldman Sachs — before deciding to shift gears again, this time to pursue an MBA that might broaden her options. That’s when she found the Joseph H. Lauder Institute of Management and International Studies. The program, then nearly a decade old, was a collaboration between Wharton and the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Arts & Sciences that offered a small, selective cohort of students the opportunity to earn a joint degree — an MBA plus an MA in International Studies — in two years.

For Le Grand, who wanted to advance her career “without losing who I knew I was becoming” in her life abroad, the program was a perfect fit. Today, she likens the education she got to a “mind-body” balance of sorts: Wharton, which gave her the tools to advance professionally, was for the mind. But the Lauder Institute and all that it entailed? “That was the heart,” she says. “That was who I was.”

Lauder Culture Quest — an Amazing Race-style program in a different locale each year — in South Africa, 2012

Indeed, after nearly three decades and an illustrious globe-trotting career with Disney, Le Grand is where she originally set out to be — in Paris, where she now runs her own consulting business. She’s also the newly minted president of the Lauder Institute Alumni Association (LIAA) at a moment when the Institute is hitting a fresh new milestone: This fall marks the program’s 40th year of sending students like Le Grand — upwards of 2,000 of them to date — on their paths all around the world.

“Leonard and I wanted something we could not find when we were students — to learn how to be global business leaders with a real understanding of different cultures,” says Ronald S. Lauder W65.

The work of helping shape so many individual international careers was just one part of the vision that Leonard A. Lauder W54 and Ronald S. Lauder W65 shared when they first dreamed up the idea for their Institute. What the brothers envisioned some 40 years back, Ronald says, was an entirely new way to think about and teach international business: “Leonard and I wanted something we could not find when we were students — to learn how to be global business leaders with a real understanding of different cultures.”

Ronald Lauder at Lauder Global Alumni Weekend 2022 (Photo: Shahar Azran)

Then, as now, world-class business acumen and professional expertise were givens at Wharton. But when it came to working in international roles, says the Institute’s original director, Jerry Wind, the Lauder Professor Emeritus of Marketing, “We believed you couldn’t be truly effective unless you were comfortable.” And that, he says, required an equally world-class education in language, history, geopolitics, culture, and regional economics; it meant spending time in close fellowship with peers from around the world; it meant immersive travel and internships abroad; it meant a deep understanding of both the local and the global and how they intersect.

Thus the ground-breaking Lauder Institute was born — and immediately began the work of transforming lives, transforming global business education, and even transforming Wharton itself, which was already shifting from a U.S. school that welcomed international students to a full-fledged international school. Lauder officially tipped the scales.

Former Lauder director Mauro Guillén

Even more notable than all of that, maybe, was just how prescient, how innovative, the idea of the Institute really was. Not only was the business world of the early ’80s far less interconnected than today’s; also, says former Lauder director Mauro Guillén, the William H. Wurster Professor of Multinational Management and vice dean of Wharton’s MBA Program for Executives, there was simply nothing else like this program in any academic realm. This is still true, Guillén adds: You don’t often see this level of interdisciplinary cooperation from this caliber of school, or the extraordinary resources available to the students. Not to mention the vital force that is the Lauders themselves. Far beyond just writing checks, Guillén says, the family has brought a depth and consistency of engagement to the program that are irreplicable.

Marina Kunis Jacobson G93 WG93 was drawn to Lauder’s “Renaissance-style education.” The Institute’s global perspective “influenced how I approach most everything,” she says.

The singularity of the Institute is something that struck Marina Kunis Jacobson G93 WG93 when she was considering expanding her education. Before arriving at Lauder, Jacobson (born in Ukraine, grew up in the States, studied Russian at Lauder) was working on Wall Street and contemplating a PhD. When she heard about Lauder and its “Renaissance-style education,” it sounded almost too good to be true. As it turned out, the global perspective Lauder nurtured while she was there didn’t just impact her career trajectory from media to equity research to CIO. “It influenced how I approach most everything,” she says.

Today, not only is Jacobson grateful for the education, but — even as a seven-year Lauder board member — she remains impressed by what the Institute offers, what it accomplishes: “I still can’t believe a program like this exists.”

Like many great inventions, the Lauder Institute began with a problem that needed fixing. It was the late 1970s, and the Carter administration had just put out a report suggesting that an overall lack of cultural education among Americans was creating a “serious barrier” to doing business in an increasingly global economy.

Lauder-Fischer Hall opening in 1992

Of course, Leonard Lauder didn’t need a report to know that: The then-CEO and president of the family-founded cosmetics giant Estée Lauder, Inc., had seen firsthand the cost of some “wonderful bloopers” that his own firm made abroad. There was, for instance, the time they’d almost run an ad in Italy with a model holding an armful of lilies — a flower most associated with funerals in the country. There was also the company’s “room-and- closet spray” designed for sale in England — a project that went forward until an associate there called to mention that “closet,” for the Brits, was a toilet.

Droll as such “bloopers” may seem now, the realization that American businesses and professionals were at a disadvantage in an increasingly connected and competitive world was a serious one, and it spurred action from Leonard and Ronald. The brothers committed $10 million to Penn for the founding of the new globally focused Institute that would train “21st Century Renaissance men,” as Leonard put it. (The gift was reported at the time to be one of the largest ever given to a U.S. business school.)

Founding Lauder director Jerry Wind and William P. Lauder W83

It took a handful of years and a great deal of interdepartmental cross-pollination and planning, as Wind tells it, but by October of 1983, Penn and Wharton joined the Lauders at the Pierre Hotel in New York City to announce the formation of their new Institute. They named it for their father, Joseph, who had founded and grown the family business alongside his wife, Estée, and had died the previous January. In attendance was then-Penn president Sheldon Hackney, who talked about “a new generation of executives with the cultural sophistication to become citizens and leaders of the world,” though it’s unclear who was listening, as the famed Estée was also there. “She stole the show,” Wind recalls.

From the very beginning, it was obvious the program was something special. First, there was the distinctive curriculum, packed with regional immersion and international internships as well as the carefully curated coursework across the social sciences, language, business, and more. (Students at the time could choose from seven languages and four regions; today, it’s 11 languages — including Italian for 2024 — and five regions, plus a global program option.) Then there was the intimate size of the cohort, which was — and still is — deliberately small and diverse. The first class included 25 Americans and 25 international students, an intentional recruiting decision designed to encourage real cross-cultural camaraderie and understanding, Wind says.

Students on a Lauder Intercultural Venture in Thailand, 2023

Also in play, he adds, was a rare sort of chemistry between the people involved in the creation of the program. He’s talking about the distinguished faculty from both Wharton and the School of Arts & Sciences, but there were also the world-class executives and a remarkably invested, star-studded board. (To wit: The first chairman was Reginald Jones W39 HON80, CEO of General Electric; other members included Bill Glavin WG55, vice chairman of Xerox; Edmund Pratt WG49, chairman and CEO of Pfizer Inc.; and, of course, both Leonard Lauder and Ronald Lauder, who at the time was the deputy assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy.)

Martine Haas, professor of management, Lauder Chair Professor, and Anthony L. Davis Director of the Lauder Institute

Yet the Institute’s most defining attribute over the years has been the students themselves. Martine Haas, the Lauder Chair Professor of Management and Anthony L. Davis Director of the Institute, puts it thusly: “The students we have here are some of the most cosmopolitan and internationally oriented of all the Wharton students, with the most amazing backgrounds.” And as diverse as they are, she says, they have something fundamental, something powerful, in common: what Le Grand calls a “spirit of adventure” — what co-chair of the Lauder Advisory Council Norm Savoie G91 WG91 thinks of as a certain brand of “intellectual curiosity, flexibility, and openness.” (Savoie grew up in New Hampshire, studied Portuguese at Lauder, and focused on Brazil.)

Today, Lauder emphasizes a thorough understanding of both the local and global contexts of business, director Martine Haas says: “I don’t know anywhere that teaches that and takes it as seriously as we do.”

Because of the global perspective Lauderites share, Haas says, many students feel like they don’t really belong to any specific part in the world — until, that is, they get to Lauder. And then? “You feel that you belong here in the world,” Haas says.

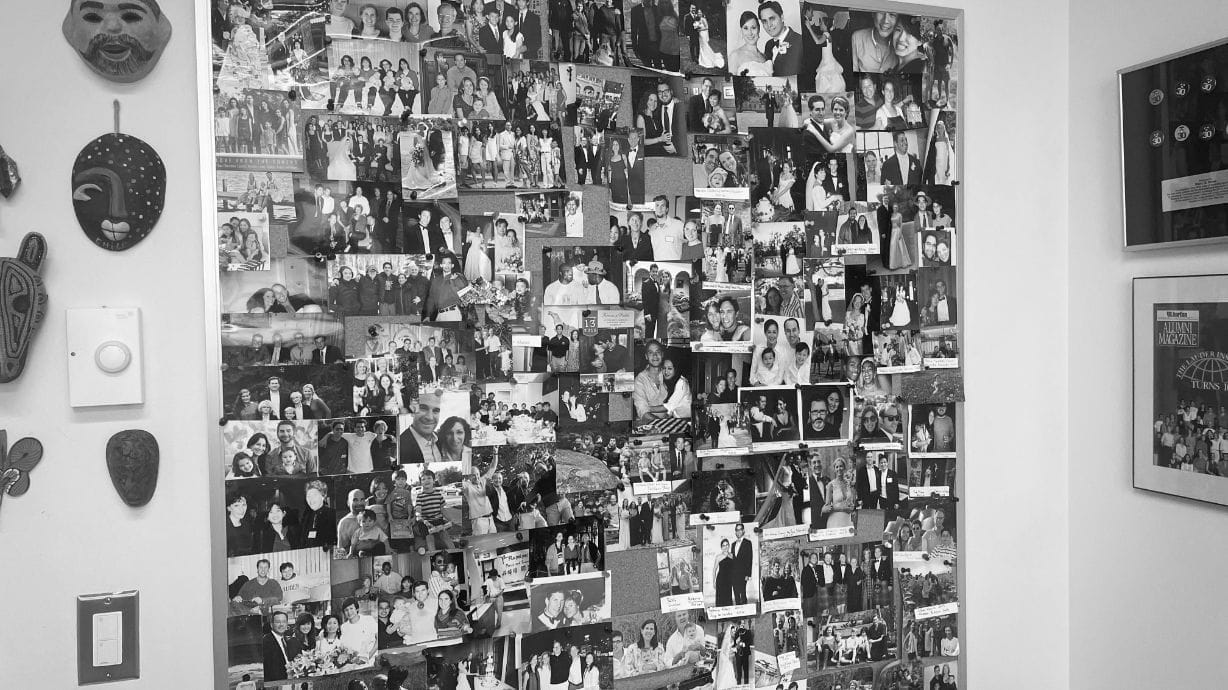

And that, she thinks — along with the immersive curriculum and small classes — is what accounts for the famously strong bonds among Lauder students and alumni. There’s “an incredibly high number, proportionately speaking, of students who get married to one another,” Guillén says, smiling. (It’s true, affirms longtime director of admissions and alumni relations Marcy Bevan GED90 GRD04, who keeps a bulletin board with their pictures. There have been 64 marriages; at least two of the children from those marriages have now graduated from Lauder as well. Though on the matchmaking front, Guillén says, “We make no promises.”)

Romance aside, the tight and deeply engaged network of students and alumni is a particular hallmark of Lauder. “Lauder Love” is more than the social media handle; it’s an attribute just about every alumnus will mention in any discussion of the Institute. “It’s one of the most loyal, dedicated groups you can imagine,” Wind says.

An Arab-language-track Summer Immersion trip circa 2009

Case in point: When the Institute launched its first-ever fund-raising campaign in 2013, an impressive segment — roughly half of all Lauder alumni — participated. (At its close in 2018, the campaign had raised some $33 million, $15 million of which was a matching gift from the Lauder family.) There’s also the Lauder Global Alumni Weekend (LGAW), a tri-annual gathering that brings alumni from all over the world to New York City for a reunion filled with events, panels, networking, and general revelry. At the first weekend in 2004, Savoie, one of the original organizers (who also helped run the fundraising campaign and launch the LIAA in 2004), was struck by how many alumni volunteered to help — at least 30 or 40, he says. The turnout of attendees was also great, he says, at roughly 400 alumni. These days, that number is closer to 1,000.

Lauder Global Alumni Weekend in New York City, 2022

The Lauder network — all those interested, interesting people — was one of the big draws for Foster Chiang C06 W06 G12 WG12 (born in Taiwan, spent his youth in Canada and Connecticut, studied Japanese at Lauder), who already had an undergraduate Wharton degree from the internationally focused Huntsman program. (That program is celebrating its own anniversary this year — see “The Huntsman Program Turns 25.”) He’d had some exposure to Lauder as an undergrad and understood the sorts of deep ties he’d make with high-caliber professionals — and as someone who was going to work for his family’s multi-national businesses after he finished his time at Lauder, Chiang wanted to make connections with people he liked and trusted, professionals he’d “want to be with in the future.” Today, the family office has seven working Wharton alumni. And like almost every other Lauderite, Chiang has stayed in touch with much of his cohort.

When it comes to Lauder alumni, says founding director Jerry Wind, “It’s one of the most loyal, dedicated groups you can imagine.”

Even beyond the connections, Chiang says, Lauder served as a sort of “reminder” for him about what he wanted and where he wanted to be. Post-college, at a time when the world tends to narrow down (you know, he says — it’s so easy to fixate on a single career path, getting married, paying off student debt, and so on), “Lauder pushed it all back open again.” While many MBAs he knew remained focused on Wall Street, on tech, or in U.S.-centric thinking, with Lauder, Chiang says, “Your friends are going to France, to Korea, the Middle East, China, Japan. It’s global, and so you think in those terms.”

Students taking notes during a Mauro Guillén lecture on campus

The global outlook is something Claudia Massei G12 WG12 cherishes, too. Massei (born in Brazil, studied Spanish at Lauder, now based in Germany) was a born traveler and a natural linguist who spoke five languages by the time she arrived at Wharton. Not only did she appreciate finding a likeminded peer group at Lauder; she says the program opened her eyes to perspectives she had never much considered as someone with an engineering background: how politics, history, and the arts all interconnect, and “all these different lenses you never looked at before.” But what she appreciated most of all? The encouragement she found at Lauder to pursue her goal of an international career.

Therein lies what Guillén calls “the single most important legacy of the Institute” — the Lauderites themselves, some 2,000 of them, spread across the planet with careers in more than 70 countries. “It’s all of these people who have embraced a global mind-set,” he says, “working somewhere out there in the world.”

O

bviously, much has changed in the world since the first class of Lauder scholars began their studies. There has been a technological revolution, countless political revolutions, global power shifts, economic booms, upheavals and meltdowns, and a once-in-a-generation pandemic. But as life and international business have evolved, so, too, has the Institute, adding to its offerings a JD/MA plus new languages to study, an African program (the first of its kind in the world), the Global program designed for students already proficient in languages, new fellowships to expand Lauder’s reach, and fresh cultural opportunities, like the deep-dive Lauder Intercultural Venture travel experiences during fall and spring breaks. The result is an Institute that today emphasizes a thorough understanding of both the local and global contexts of business, Haas says: “I don’t know anywhere that teaches that and takes it as seriously as we do.”

Leonard Lauder speaks at the Lauder-Fischer Hall’s groundbreaking circa 1989.

And still there are, as ever, more changes coming down the road, Haas promises. That’s simply the nature of innovation, and what’s necessary to develop professionals poised to lead at what Haas calls an “exciting and important time in terms of global business.” Haas also points to the growing alumni base, which is creating more and more opportunities for both students and alumni to connect and learn. Le Grand and fellow LIAA board member (and co-chair of LGAW) Deepti Tanuku G10 WG10 are in the midst of helping transform the “startup” that is LIAA into a “long-term association that will serve the greater alumni community,” as Le Grand says, to keep creating moments and events for engagement, connection, advancement, and learning.

Amid all the growth, however, what won’t change are the tenets of the program that have been its bedrocks since its founding, those key components of the Lauders’ original vision: the commitment to 21st-century Renaissance men and women. The forward-thinking vision. The close-knit cohorts, which have grown slightly but still hover around 70 students per year. The excellent faculty and executive leadership. The adventurous, open, curious students. And — most of all — “a sense of family,” Guillén says, which began with the Lauders themselves, brothers in the family business who have always taken seriously what it means to see their name on the Institute.

The Lauder Institute building today

By all accounts, that familial sense extends to the students, too, in part because the relatively small size of the program provides a soft landing among people who really know one another. It’s also because, as Le Grand says, Lauderites rely on each other. They connect with fellow alumni, and “tap into and also give to them.” Just like family.

Today, Ronald Lauder says, the Institute represents the vision that he and Leonard had some 40 years ago. “This program, and its alumni, surpass what we imagined possible. We’re immensely proud of the Institute and the community of global leaders it has produced in the last four decades,” he says. “We are confident the Institute’s coming decades will be even brighter.”

Christine Speer Lejeune is a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia.

Published as “Four Decades of Global Impact” in the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Wharton Magazine.