Once a financial tool only for the very rich and well connected, hedge funds have proliferated in recent years. With more than 8,000 funds in existence, the industry is becoming increasingly crowded.

And yet, for the average American investor, hedge funds are a mysterious business—how they are managed, and even how to access them. A Wharton alumnus is helping to change that.

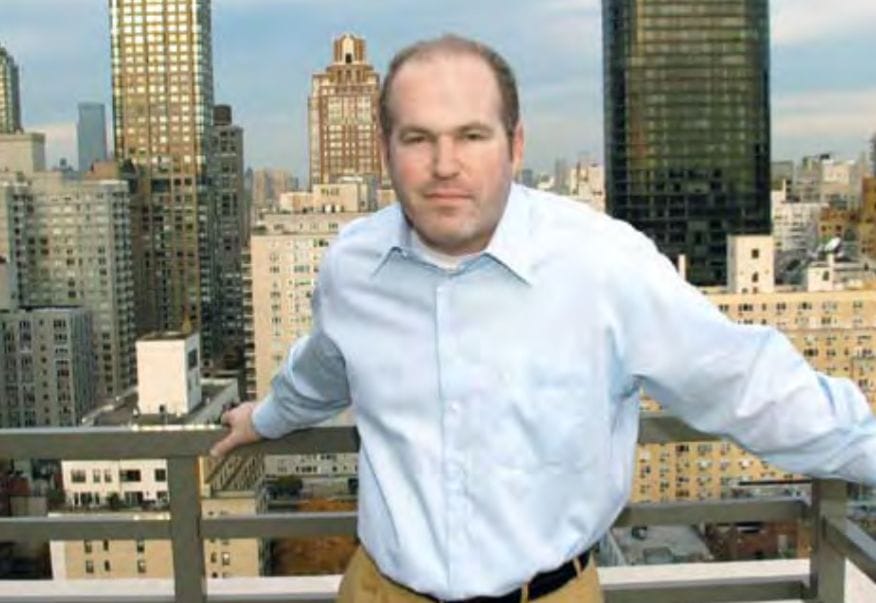

In 1998, Cliff Asness, W’88, E’88, co-founded one of the largest hedge funds in the world, Greenwich, CT-based AQR (Applied Quantitative Research) Capital, which manages more than $23 billion. Most of those billions do not belong to the elite individual investors who dominated hedge funds in the past, but to institutional investors—especially university endowments and public pension funds.

Asness and his partners founded AQR just as the Internet was bubbling—a seemingly unfortunate time, when the quantitative rigor that is AQR’s hallmark seemed stodgy compared to the freewheeling valuations in the new economy. In its first years, AQR leaked money, losing 60% of its value. While AQR’s institutional investors stood their ground, many private investors were abandoning other hedge funds.

By 2001, Forbes called the hedge fund industry a folly: “You don’t have a hedge fund to brag about at lawn parties? That could be because you’re too timid to swing for the fences, as these private investment partnerships often do with leverage and exotic derivatives. It could be because you are not well connected… Maybe you are not rich enough… Or maybe you are not in a hedge fund because you know better.”

In fact, it was the perfect time for AQR. In 2000 Asness had written a paper of his own—”Bubble Logic,” a takedown of nonsensical, unsustainable stock prices—that was never published but ended up being both prescient and influential. It was passed among money managers, read in academia, and quoted in the business press.

And Asness turned out to be right. The power of AQR’s market-neutral investment strategy is now benefiting a wider swath of investors who were once left to ride out rough patches in the economy unprotected.

An Epiphany at Wharton

Self-described as a somewhat “disinterested” student in high school, Asness had always thought he would follow his father into law. Instead, Asness found a new passion for numbers ignited by his Wharton experience. As an undergraduate, he double-majored in finance at Wharton and computer science at Penn Engineering as part of the Management and Technology program, finishing the typically five-year program in only four years and graduating summa cum laude.

Working as a research assistant in the Finance Department, Asness discovered an interest and affinity for research in finance, specifically in portfolio management, which led him to follow in his mentors’ footsteps and pursue a PhD in the discipline. After Wharton, Asness went straight to graduate school at the University of Chicago. There, he became a teaching assistant for Eugene Fama and wrote his PhD dissertation on the performance of momentum trading, buying stocks with rising prices. Years later, Asness would combine the insights from his research with those from his mentors to make money in the financial markets.

After Chicago, Goldman Sachs offered Asness the chance to start a quantitative strategies group to use the latest research to make money in the financial markets. Asness accepted. Asness’s group delivered high returns in their first few years, even doubling their money in one year. After only two years, Asness’s team was already managing $7 billion, and they barely had a month in which they lost money.

In November 1997, Asness decided to leave Goldman and start his own hedge fund, rebuilding his computer models with three other founding partners. Asness and his team had no trouble attracting investors for their fund, AQR. Within five months of launching AQR they raised $1 billion, which was believed to be the largest amount ever raised by a startup hedge fund at the time, according to the New York Times. Today, Asness and his team make money by continuing to apply the latest financial research to finding and capitalizing on inefficiencies in financial markets around the world.

For a man who relies on hard numbers to make financial decisions, Asness surprisingly attributes much of his success to good fortune. “I don’t think enough people who are successful give enough honest credit to luck along the way,” he said. For example, he almost became a lawyer and would never have considered a career in finance had it not been for his pivotal experiences at Wharton.

Investment Philosophy

AQR’s core investment philosophy is the combination of value and momentum investing: buy value stocks with positive price momentum and sell short growth stocks with negative momentum. AQR’s strategy combines the insights of Asness’s research on momentum trading with principles of value investing. In a famous study, Fama and his colleague Kenneth French found that value stocks outperformed growth stocks more than half the time (in fact, in more than two-thirds of the years), which is more often than expected under the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). (The EMH states that investors cannot beat the stock market consistently because all relevant information is already built into stock prices.) Asness further tested the EMH by studying the performance of momentum trading, buying stocks with rising prices. He found that momentum trading also worked better than the EMH suggested it would.

Today, AQR applies its strategy of buying undervalued assets and shorting overvalued ones not only in the stock market but in 19 other financial markets as well. The key to the strategy’s success, says Asness, is accurately and clearly defining value and momentum. To implement his firm’s quantitative investing strategy, Asness and his team develop and “apply statistical models through giant computer programs to try to make money in the investing field.”

AQR is also widely diversified, usually buying and selling blocks of 400 stocks at a time. The company buys the 400 most undervalued and sells short the 400 most overpriced. As Asness describes, “We are about the ideas of value and momentum and a few other things paying off over time and how to insulate ourselves as much as possible from the vagaries of any one company. A traditional [fund] manager is much more about, ‘How do I get the vagaries of any one company right.’”

The Future of Hedge Funds

In 2005, Asness was invited to write an article for the 30th anniversary of the Journal of Portfolio Management (JPM). The list of authors is a veritable who’s who of leading investing experts and researchers. Among them were Andrew Lo, director of MIT’s Laboratory for Financial Engineering and for whom Asness served as a research assistant when Lo was a professor at Wharton, and Bob Litterman, who succeeded Asness as head of the Goldman quantitative trading group Asness started. He later presented his findings to an audience of 85 people at an event of the Wharton Hedge Fund Network in New York.

In his article for the anniversary edition of JPM, Asness outlined a balanced account of his vision for the future of the hedge fund industry, detailing both the upsides and downsides of hedge funds. In Asness’s opinion, “What hedge funds should be doing is separating market exposure from an attempt to add value. People should be able to buy these separately.” Thus, Asness envisions a future in which people’s portfolios can include only index funds and hedge funds. The indices capture the returns in the financial markets, thus providing market exposure, and the hedge funds add value in excess of the market returns. However, Asness believes many changes need to take place in the hedge fund industry before investors can hold such a portfolio.

Those changes include transparency issues for hedge funds. As Asness describes, “One sticking point between institutional investors and hedge fund managers that is slowing down progress toward the hedge-fund-plusindex- fund world is the lack of transparency in hedge funds (they often do not tell their investors what they are long and short). Many institutions are not comfortable without transparency.” Going forward, institutional investors and hedge funds will need to find some middle ground with respect to transparency and disclosure.

In addition, as more hedge funds try to capitalize on inefficiencies in the financial markets, it will become increasingly harder for funds like AQR to find those inefficiencies. However, Asness believes an equilibrium amount of market inefficiencies will eventually be reached.

If the market contains few inefficiencies, many hedge funds will exit or their investors will take money out, but then inefficiencies will creep back in. “One of my professors once said, and he got this from someone else, that there will be an ‘efficient amount of inefficiencies in the market,’” says Asness.

If this is the case, the criticism of top-secret computer models—black box investing—may be misplaced. As Asness told the New York Times, “You know, human beings have a black box, too. It’s called the brain.”

Han Hu W08, is a first-time contributor to Wharton Alumni Magazine.