In last June’s world economic summit in Denver, during a meeting of the G-7 nations (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and United States) and Russia, U.S. government officials crowed about America’s booming economy. Low inflation, low unemployment and the unleashing of entrepreneurial creativity was fueling a raging bull market generating envy around the globe. Many were asking if the American model of entrepreneurial capitalism and free markets is so successful that it should be copied worldwide.

But some economists, especially in Europe, believe that America still has not adequately dealt with the downside of its system – inequalities of income and wealth, below average public education and health services and the social problems that follow.

Why do Europeans and Americans view the U.S. model so differently? According to Franklin Allen, Nippon Life Professor of Finance and Economics, some people believe that the current economic models in countries like France and Germany are less than efficient because their huge social safety nets have become too costly. In addition, rigid labor laws tend to slow new hiring and government regulations discourage entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, many French and German citizens believe that the U.S. model, with its recent reliance on downsizing and benefits slashing, is too harsh. They still believe that society should guarantee its citizens a minimum standard of living. France, although in the midst of major economic difficulties, has rejected the U.S. model outright.

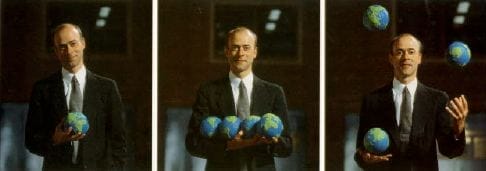

Allen, one of the world’s leading researchers on the comparison of global financial systems and financial strategy, believes that many world leaders have not looked seriously at the different components of each other’s models. Is there a system that can combine jobs and growth with an acceptable level of economic fairness?

“The world has very different types of financial systems, even though we tend to think of all the major economies as capitalist,” says Allen, whose most recent research looks at the financial systems of the U.S., Germany and Japan. “In the U.S., the notion of capitalism is based on Adam Smith’s idea of the ‘invisible hand.’ Firms exist to maximize profit and consumers exist to maximize their own ends, and the invisible hand of the market supposedly allocates everything efficiently.”

The structure of a country’s financial system can have a big impact on the types of investments firms undertake and the efficiency with which they are carried through, says Allen, a British native who earned his doctorate and master’s degree in economics from Oxford and a BA from the University of East Anglia.

“Market systems are probably better in the long run because they encourage innovation among firms,” Allen says. “For example, railroads in the 19th century and industries such as automobiles, computers, aircraft and biotechnology in the 20th century were arguably developed in the U.S. primarily because of the existence of the stock market.

“There is a tendency to think that what the U.S. does is good and that other financial systems are backward, which is not necessarily the case,” says Allen. “The Europeans are just starting to move towards market-based systems, but it’s not clear that it’s a good thing.” Financial markets, while they offer many advantages, can also cause big problems. “The most dramatic example is the situation in Japan, which had huge bubbles, or runups, in stock prices and real estate followed by a huge collapse in those prices and then problems in the banking system. A similar situation occurred in Scandinavia in the mid 1980s.”

Winners and Losers

Traditional superpowers, like the U.S., Germany and Japan, and upstarts, like China and Korea, will be strongly affected by a shakeout in the world economy, says Allen. That shakeout will produce some clear winners and losers.

“The U.S. will have an advantage, because various countries are moving toward a market-based system and the Americans are already experienced in this,” Allen says. “China, if it continues to grow at its current rate, is poised to become the number two economy, aided by the capital and management experience of the ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia. Those factors, combined with a well-educated workforce, could be very powerful in the country’s continued economic development.”

Events such as the Chinese takeover of Hong Kong and the likely adoption of a single European currency will also have a big impact on the global financial system, Allen notes. Within 20 to 30 years, the Euro could become a major challenger to the dollar as the world’s leading currency.

He also emphasizes that one should not focus only on a nation’s current economic strength when predicting its long-term prospects. “Korea was one of the world’s poorest countries 50 years ago. Today, it is emerging as an economic force.”

When the Bubble Burst

In Japan, Allen says, “firms are much more like a group of people working together and shareholders are viewed more like bondholders. They need to be given a return, but that’s not the main purpose of the firm. The firm’s primary function is to provide employment and look after the workers.”

Until the end of the 1980s, Japan was regarded as the postwar economic miracle, rising from ruin in the 1940s to world power status within several decades. But Allen says that Japan’s recent economic problems, like its success, were rooted in its unique form of capitalism, whereby the structure of institutions and government reduced the level of risk faced by individual firms and other agents compared to a U.S. style market economy.

In market capitalism, risk must be compensated for and so is costly, Allen notes. “But the Japanese structure attempted to eliminate risk and its associated cost. Japan achieved an economic miracle, but was simultaneously laying the groundwork for its downfall.” According to the Wall Street Journal, total asset value suffered a loss of close to $10 trillion during the first half of the 1990s, equivalent to Japan’s estimated economic loss from World War II.

That’s because controlled risk capitalism created a “moral hazard” among Japanese private-sector investors. Perhaps the best example, says Allen, was the real estate industry’s pursuit of ever-rising property prices without proper regard for investment return. “They were investing with borrowed funds, which in some cases were guaranteed by the government. To the extent that there is a moral hazard problem between investment and fund managers/owners because the fund managers are investing with other people’s money, the same problem arises in the equity markets.”

Compounding the problem, the Bank of Japan provided funds to fuel hyperspeculation in the equity and real estate markets, Allen notes. The economic bubble burst in the early 1990s.

Japan is fighting its way out of a six-year recession. An announced overhaul of its financial industry is set for completion by 2001, along with deregulation in the electricity and telecommunications industries. As the economy becomes increasingly unfettered, some experts argue that pervasive group behavior will not be as rewarding, allowing Japan to emerge as an economic power with competitive companies and individual entrepreneurs.

“It remains to be seen whether this will actually happen,” says Allen.

For Your Information

One of the main differences between financial systems is the way that information is generated and used, Allen notes. “Different financial systems assign different roles to the price system in conveying information for the efficient use of resources. They also provide different incentives for investors and creditors to monitor firms.”

Allen, who has conducted much of his country comparison research with colleague Douglas Gale of New York University, says that an important difference between the U.S. and Germany is the amount of information that is publicly available. In the U.S., for example, the large number of firms that are publicly listed – and the SEC requirements that they release extensive accounting reports – makes available a great deal of financial data.

“This has implications for the allocation of investment,” Allen says. “The wide availability of information helps firms to make good investment decisions. Firms can also make better decisions about whether to enter or exit an industry. This allocational role of the stock market has traditionally been viewed as one of its most important attributes.”

In contrast to the U.S., few companies in Germany are publicly listed and those that are do not release much useful accounting information, Allen says. This can be advantageous, because it may reduce the risk born by investors. But it also raises the issue of how investment is allocated. Without the price signals and other information available to U.S. firms, German firms would appear to be at a significant disadvantage in making investment and entry decisions.

Meanwhile, banks in Germany are heavily involved in the control of industry and form long-term relationships with firms. It can be argued that a German type of financial system, where a small number of large banks play a prominent role, may permit some substitute mechanisms.

“If banks have a large amount of information about the profitability of firms, they can use this information either directly by advising firms or indirectly when they decide whether or not to grant loans to finance investments,” Allen says.

Although substitute mechanisms allow duplication of many functions of the market, there remain some apparent disadvantages to reliance on intermediaries, Allen notes. Most importantly, without an active stock market, it may be difficult to decide on appropriate risk-adjusted discount rates.

Access to seed money is also important to the success of financial systems. “Both Japan and Europe are becoming increasingly worried about their lack of venture capital,” says Allen. “The absence of a liquid stock market makes it difficult to cash out. Also, the hierarchical nature of banks compared to the horizontal nature of markets makes it harder to raise money because markets have critical input from numerous influential people, whereas a bank gets input from just a few.”

Another important factor, says Allen, is the role of the financial markets. “In the U.S. and U.K., the financial markets are much more important, whereas the markets play much less of a role in Japan, Germany or France where institutions, banks and insurance companies in particular, are much more important.

“There are advantages and disadvantages to both systems,” Allen continues. “For example, competitive financial markets tend to impose a great deal of risk on individuals. People in the U.S. hold lots of equity, whose market value varies significantly over time. This can have disastrous consequences for individual shareholders. A classic example was the roughly 50 percent drop (in real terms) in the U.S. stock market during the early 1970s. People who had accumulated wealth in the stock market up to then were hurt badly.”

Other economies do not bear as much financial risk. “For example, in Germany and Japan, people hold much of their wealth in bank accounts and other fixed instruments, so they’re not affected as much by how the stock market moves.”

Riding a Wave Vs. Creating Value

A critical factor in fueling a global economy is how firms integrate finance and strategy to create shareholder value. It’s a subject that has recently been the focus of research by Allen and Wharton colleague John Percival.

“In a financial system where capital markets are important firms need to worry about how to create value,” Allen says. “In a strict sense, it’s increasing the stock market value. In a wider, more general sense, it’s using resources efficiently. For example, Coca-Cola and General Electric are two highly successful companies that look very carefully at where value comes from.”

Some time ago, Allen says, Coca-Cola followed other companies by diversifying across industries. Subsequently it reexamined that strategy and concluded that the soft drink business was where the company was most successful in creating shareholder value. Coca-Cola refocused the business and saw its value increase substantially.

To understand the relationship between strategy and finance it is useful to draw a distinction between companies that ‘ride a wave’ and companies that create value, Allen says.

“Riding a wave simply requires being in the right place at the right time with the right characteristics. Revenues grow, the company is profitable and the stock price rises. It is easy to fall into the trap of assuming that these financial outcomes are the direct result of strategy. Profitability is, however, extraordinarily fragile.

“For example, Apple had a great product, which it developed at the start of the boom in personal computers. So Apple was able to ride the wave of the PC revolution for several years and did extremely well.”

But a company must have a passion for the objective of creating value for shareholders, he adds. “If it is not the focus of strategies it will not happen by chance. Capital markets may be content with companies that ride waves. The implications for companies that fail actively to create value can be devastating, however. IBM, Apple and Kodak had outstanding personnel and excellent products, but suffered greatly from the cresting of their waves. IBM is a particularly good illustration of this. They didn’t pursue personal computers because they feared that PCs might erode their highly profitable mainframe business.”

A firm that has been exceptionally successful in creating shareholder value, says Allen, is Emerson Electric, a $9 billion U.S.-based manufacturer of relatively low technology goods such as electric motors and compressors. It has had 40 years of increased earnings and has earned at least its opportunity cost of capital for most of these years, creating a large amount of shareholder wealth.

Emerson has a sophisticated planning process: each division is required to prepare a detailed five-year plan which contains projections of financial results and a discussion of why the projections are sensible. Managers use the Dupont System, a simple method for trying to understand how returns are generated. It is the product of margins (i.e. income/revenues) and turnover (i.e. revenues/assets). It thus decomposes rate of return (income/assets) into two components which are determined by operating and marketing strategies, Allen explains. Executives responsible for division-wide planning are grilled by the senior management of the company. Managers are required to display an in-depth knowledge of how their plans will be implemented and why the financial projections presented are realistic in terms of the marketing and operating strategies involved.

The Wal-Mart Approach

To help understand the relationship between strategy and the creation of value, Allen and Percival recommend employing the Dupont System “because at some level most strategies involve a trade-off between margins and turnover,” Allen says. “The system allows simple insights into the effect of the various possibilities on the rate of return. The system is most valuable when used prospectively, providing a way for managers to gain insights about the return a strategy will generate. It forces management to focus on how rate of return comes from the competitive conditions in a product market and customers’ reactions to management’s decisions. Rate of return does not come from margins or turnover but from margins and turnover. Actions that increase margins tend to reduce turnover and vice versa.”

For example, if a firm moves upmarket by increasing its prices, margins will increase but typically turnover will fall. The trick in creating value is to increase margins without lowering turnover or vice versa.

Look at Wal-Mart’s success, says Allen. “Traditionally it has been manufacturers that develop customer loyalty, a situation that gave manufacturers the opportunity to charge higher prices and thus earn higher margins. Retailers historically focused to a greater extent on higher turnover.”

Wal-Mart, on the other hand, has been able to create a strong base of loyal customers and effectively combine high margins with high turnover. As a result, the company has consistently earned higher returns than its competitors.

Integrating Marketing, Operations and Finance

Finance must have two separate roles, Allen says. One continues to involve the tasks that finance staff have traditionally performed, such as recommending and implementing capital structure and dividend policies and risk management. The other role, however, is not traditional. It is the development of the financial implications of non-financial strategies.

This second role for finance, says Allen, involves the process of asking and answering questions regarding how a proposed strategy will provide future cash flows that will create value. “For example, ‘How can we use the improved market position that comes from a proposed strategy to earn more than the opportunity cost of capital?’ This is essentially what Coca-Cola and GE have done so successfully in considering which businesses to stay in and which to leave.”

A key to creating value, adds Allen, is financial awareness on the part of nonfinancial people who use this thought process while formulating strategies involving competitive advantage, technology investment, pricing and product mix decisions, reengineering and outsourcing.

All discussions of strategy ultimately come around to dealing with change, Allen says. “Strategies that earn more than the opportunity cost of capital under one set of circumstances may not earn those returns when the customers, competitors, technologies and economic environment change. This was Apple’s problem. When Windows was developed the company was not able to adapt and its wave crested.”

Integrating finance and strategy is crucial in dealing with what Allen and Percival call the change trilogy: knowing when to change, knowing how to change and changing.

“Only when strategy and finance are integrated can managers avoid the pitfalls of both and make effective decisions,” says Allen. “The concepts of strategy need to be used to develop an understanding of how cash flows are generated. What is the competitive environment in which the firm operates? How are the strategies or projects a firm undertakes likely to affect its revenues or costs? What actions will competitors take in response to the firm’s changes in its products, pricing and other competitive decisions? How can the firm minimize its costs of production and at the same time maximize the quality of its products?”

For instance, far too many companies have not moved on a timely basis to eliminate or change lower profitability businesses that take away sales from their core businesses, Allen says. Bausch & Lomb, for example, failed to introduce disposable contact lenses, presumably because of its concern about the impact they might have had on the company’s existing contact lens and solutions business. The delay enabled Johnson & Johnson to enter the market for disposable lenses and gain considerable market share at Bausch and Lomb’s expense.

“The managers of firms that ride waves bear significant risks,” says Allen. “Even the most astute manager may not be able to predict when the wave will crest or crash. It’s only through a thorough understanding of how the firm creates value that executives will avoid crashes and assure consistent profitability.”