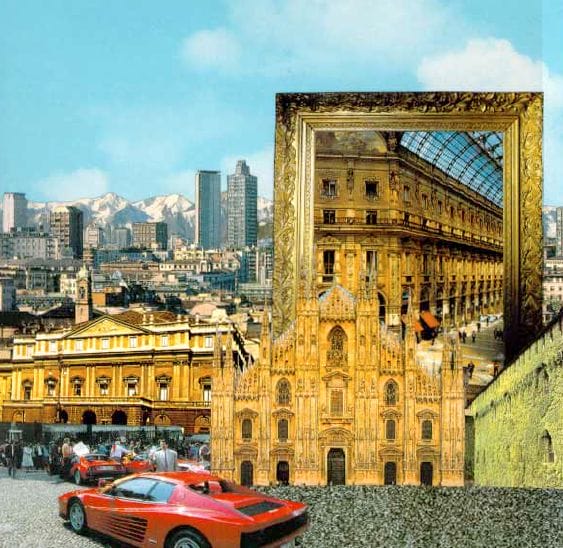

Our series on alumni in different cities makes its sixth stop in Milan, home to approximately 1.7 million residents and firmly entrenched as both the business and high fashion center of Italy. While Rome draws more tourists, Milan draws most of the country’s major corporations, including multinationals like IBM, 3M, Microsoft, Apple, and Hewlett-Packard. In addition to its charm, Milan benefits from its location – close to the major cities of Europe – and also its image of efficiency. Milan, says one Wharton alumna, “is a city that works.” In the following pages we profile several Wharton alumni who live and/or work in Milan. Mindful of the city’s reputation as a place “that offers some of the best food you will ever taste,” says one alumnus, we have included our usual list of recommended restaurants and hotels.

Asked to describe his strongest quality as a leader, Corrado Passera answers: “The ability to put together and motivate a team of very talented people who focus on the solutions rather than the problems, and who can address even the most serious difficulties with the attitude that they can be overcome.”

That ability is serving Passera well, given the substantial restructuring that Olivetti has been undergoing since Passera’s appointment as managing director in 1992. Although traditionally an office equipment/computer manufacturing company, the $6 billion Olivetti today derives almost two thirds of its revenues from systems and services and is aggressively investing in telecommunications and multimedia. It holds a controlling stake in Omnitel Pronto Italia, an international consortium which is about to launch Italy’s second cellular phone network, and has grouped its other telecommunications and multimedia ventures into a subsidiary called Telemedia.

The move to speed up entry into these areas has spawned alliances with a large number of companies, including Bell Atlantic, Airtouch, Hughes, Mannesman and Redgate.

Passera’s master plan for the company, endorsed by Olivetti chairman Carlo De Benedetti, “has five objectives,” he summarizes. “To select businesses where Olivetti already is or can become a leader at the European level, to grow more than the market, to reduce costs more rapidly than the reduction in margins, to build up telecommunications and to reshape the old company in a focused way in each of its areas of business (office products and printers, personal computers, systems and professional services).”

Olivetti has suffered from heavy restructuring charges in the last few years and experienced Treasury losses in 1994 and an erosion of market share in the highly competitive personal computer sector. Yet Passera stresses the importance of reaching the operating break-even point last year thanks to the reduction of selling, general and administrative costs (SG&A) from 28 percent to 20 percent in 1993 and 1994.

In order to be profitable in our business,” he adds, “SG&A must be closer to 15 percent than to 20 percent.”

Whatever obstacles Olivetti faces, Passera himself is highly regarded by both investors and industry observers, according to press reports. His connection with Olivetti dates back to 1977 when, after graduating with honors in business management from Bocconi University in Milan, he spent one year with Olivetti as a management trainee.

Following graduation from Wharton, he worked as a banking and finance consultant for McKinsey in Italy from 1980 to 1985. For the next three years, he was assistant to Carlo De Benedetti at CIR SpA and, from 1988 to 1990, general manager. After one year as COO at Arnoldo Mondadori Editore SpA, and a year and a half as vice chairman and COO at Espresso – Repubblica Group, he moved to Olivetti.

Passera was born in Como, Italy, and lives in Milan with his wife and two children, ages 9 and 8. He enjoys reading, sailing and traveling.

“Information technology and telecommunications are converging into the new world of information and communication technology,” says Passera. “In its 90 years of life, Olivetti has already gone through a similar cultural and managerial transition when it went from being a mechanical company to an electronic company and then to an IT company. We are ready for the next phase.”

“We do not go to foreign countries just to put our flag up and say Pirelli is here,” notes Alessandro Signorini, who is in charge of the cables export division of Pirelli, a $5.6 billion tire and rubber products company based in Milan. “We want to be serious participants in the country and also give our technical and managerial know-how to the project.”

As director of market development, Signorini is in charge of both sales and joint ventures for the $700 million cables export business. His work takes him primarily to Indonesia, Malaysia, China and other Asian countries, but also to cities in Eastern Europe. About 40 percent of his time is spent on sales and 60 percent on joint ventures.

As director of market development, Signorini is in charge of both sales and joint ventures for the $700 million cables export business. His work takes him primarily to Indonesia, Malaysia, China and other Asian countries, but also to cities in Eastern Europe. About 40 percent of his time is spent on sales and 60 percent on joint ventures.

The work can be both frustrating and rewarding. “Each time you go, you find different mentalities, different approaches, different types of problems. It’s a long-term process but in the end we have been successful in completing several joint ventures and are in the middle of establishing several more.”

Signorini was born in Naples and attended the University of Naples before coming to Wharton. After graduating, he spent a year in long-term planning at SME, two years in new business development at Eurogest, three years in the export division of Alivar and seven years as controller, international activities, at Sogene.

From 1989 to 1993 he was director of subsidiaries at Benetton. He joined Pirelli Cavi in 1993 as group controller for the worldwide cables division, and one year ago, was promoted to his current position. He and his wife and two children live in Milan.

Pirelli has had subsidiaries all over the world for much of this century, including, most recently, 100-percent owned operations in the U.S., Brazil and Argentina. “Now times are changing,” Signorini says. “We are willing to set up joint ventures because that’s what our local partners want. They say they are capable of managing the new company, though there is often long discussion on who should make the major decisions for the benefit of the joint venture. But we work things out,” Signorini adds, “And we don’t give up.”

As you get older, says Rolando Polli, who up until May was manager of McKinsey’s Italian office, “you try to make your geography a bit simpler. Geneva, Paris and Milan is more doable than other combinations.”

Polli should know. Like many consultants, his career since joining McKinsey in 1969 has been a game of international hopscotch. He started out in Milan in 1969, became a partner of McKinsey in 1976, then in 1977 transferred to Paris, and in 1979 to Toronto. In 1981 he became manager of McKinsey’s Madrid office but also co-managed the Italian office, “which was a bit of an oddity,” he admits. In 1985 he went back to Canada and then in 1986 back to Italy, where he was manager of the Milan office until May. He remains a director of McKinsey, based in Geneva but with clients and offices in Milan and Paris as well.

Polli should know. Like many consultants, his career since joining McKinsey in 1969 has been a game of international hopscotch. He started out in Milan in 1969, became a partner of McKinsey in 1976, then in 1977 transferred to Paris, and in 1979 to Toronto. In 1981 he became manager of McKinsey’s Madrid office but also co-managed the Italian office, “which was a bit of an oddity,” he admits. In 1985 he went back to Canada and then in 1986 back to Italy, where he was manager of the Milan office until May. He remains a director of McKinsey, based in Geneva but with clients and offices in Milan and Paris as well.

“Milan is by far the center of economic life in Italy,” says Polli, who retains three large clients in the city. “The recession in 1992-93 was difficult, and at the same time we had the ‘clean hands’ investigation when lots of managers resigned or had to leave. Working in Italy was somewhat pyrotechnic then: You didn’t know if the guy you worked for would be sent to prison, or what. But now the economy has picked up. We have a growth rate of three percent, a little better than the European average. And more people are employed again.” McKinsey’s Rome and Milan offices have 130 professionals between them, with the majority of their clients in the services and manufacturing industries and about 35 percent in the financial institutions sector.

Polli was born in Milan and graduated from Bocconi University in 1962. He and his wife, who is English, live in Geneva and have two children, a daughter who recently graduated from Dartmouth and a son who is at Stanford.

Although Polli studied marketing at Wharton, “over time I became more of a financial institutions man. I have moved a lot in my career. Focusing on financial institutions was a useful way to adapt to a new country.”

Maggie Dupresne calls it her “nonstop MBA.” As a program coordinator with the Ambrosetti Group, a 60-person consulting and business seminar firm headquartered in Milan, she organizes seminars for business leaders in Italy on subjects ranging from new theories of management to the recently formed World Trade Organization to the European political situation.

“Italians here are coming out of the same recession that America experienced a few years ago,” says Dufresne. “Therefore hot topics include subjects like how to restructure after a recession and the benefits of business reengineering. But Italians are curious about everything, not just management issues. I find them more interested in international affairs than the average American, partly because Italy is small and it is just one country in the European Union. Other Europeans are the same way — very eager to understand what is going on outside their own borders. And obviously decisions made in Europe have a big impact on the Italian economy.”

“Italians here are coming out of the same recession that America experienced a few years ago,” says Dufresne. “Therefore hot topics include subjects like how to restructure after a recession and the benefits of business reengineering. But Italians are curious about everything, not just management issues. I find them more interested in international affairs than the average American, partly because Italy is small and it is just one country in the European Union. Other Europeans are the same way — very eager to understand what is going on outside their own borders. And obviously decisions made in Europe have a big impact on the Italian economy.”

Dufresne is the contact person for speakers, one third of whom are business school professors, including several from Wharton. Also invited are members of the current government. “We do that frequently,” she says, “partly because the government changes often, but also because key members change. We have had the prime minister, the treasury minister, commissioners of the European Union in Brussels, the former head of GATT and the current head of WTO, among others.” The speakers come to different parts of Italy for anywhere from half-day to full-day sessions.

Dufresne also does workshops for foundations and private groups. In the course of a year, she has contacts with approximately 100 speakers.

Dufresne grew up in Springfield, Mass., and graduated from Smith College. She worked for a year in Boston as an administrator in a psychiatric clinic, then moved to Italy with her husband, who is Italian and a professor of business history at Bocconi University. In Italy she spent five years working for her husband’s father, the owner of a shipping and maritime agency, before returning to the U.S. to attend Wharton.

She and her husband have a son, 7. They live in Milan.

“I consider Milan one of the most efficiently organized cities in Italy in terms of getting things done,” she says. “There is a business mentality here. When I schedule a meeting with someone for 11 a.m., the meeting starts by 11:02. In Rome, an 11 a.m. meeting doesn’t start until 11:45. It can be very frustrating if you are trying to stick to a schedule.”

Alberto Lotti, head of the mutual fund management division of the giant insurance company RAS, says his biggest challenge externally as head of the 50-person investment arm is to increase market share from its current 7.5 percent up to 10 percent. Internally, his priority is to grow and train portfolio managers. “We have trouble finding qualified candidates and our turnover rate is high because we have many competitors,” says Lotti.

Aside from that, the investment business is going well. Gestiras runs 15 mutual funds of all kinds, including equity, bond, domestic, international and emerging economies, with about $10 billion under management. “We are mainly value players,” he says. “We have a moderate attitude toward risk and we tend to buy assets we believe are undervalued.”

Aside from that, the investment business is going well. Gestiras runs 15 mutual funds of all kinds, including equity, bond, domestic, international and emerging economies, with about $10 billion under management. “We are mainly value players,” he says. “We have a moderate attitude toward risk and we tend to buy assets we believe are undervalued.”

Lotti was born in Milan and graduated from Bocconi University. He joined RAS in its research unit in 1982 and eventually was put in charge of the company’s U.S. division, located then in New Jersey (and since sold). After that he joined the investment team, and two years ago, was named general manager.

He admits to being very good at soccer, playing in what spare time he has on an amateur men’s soccer team. He also lectures on international finance to university students.

“The Italian economy is doing well,” Lotti notes. “We are growing at four percent a year and of course we have a big advantage from the weak currency. Right now, our economy seems to be the strongest one in Europe.”

Paolo Bordogna was born in Bergamo, Italy, an old town about one hour outside of Milan. He has chosen to settle there with his wife and two children, ages 7 and 5, even though it is more of a weekend home for him than anything else.

“I travel a lot,” he says with understatement, noting that this past year alone, his work with one particular client has taken him to South America, Turkey, England, Spain and Germany. “I follow my multinational clients wherever they go,” he says.

“I travel a lot,” he says with understatement, noting that this past year alone, his work with one particular client has taken him to South America, Turkey, England, Spain and Germany. “I follow my multinational clients wherever they go,” he says.

Bordogna has been with BCG since he graduated from Wharton, first in their Paris office, and then in Milan. About 50 percent of his clients are in banking in Italy and the other 50 percent in the industrial goods and high technology sectors with operations worldwide.

Bordogna did his undergraduate work in engineering in Milan and spent 18 months as a brand assistant for Procter & Gamble in Rome before attending Wharton. For the past three years he has lectured on managing technology and organizational issues at Wharton’s International Forum in Bruges.

On winter weekends he skis, and in the summer, plays golf and flies helicopters. “BCG started in Italy with a limited network, but we are now big and well-established,” he says. “It helps that the Italian economy is very strong. With so much changing it’s an interesting time to do business here. Telecommunications was privatized this year, and the banking sector is going through a period of mergers and acquisitions. It’s a lot of fun.”

Gloria Leporati seems to have balanced an interest in academics with a successful career in money management. She taught international finance at Bocconi University for five years after graduating from Wharton, and then, in 1987, was hired as an economist and Japanese portfolio manager at Gestiras, the investment arm of RAS (where she reports to Alberto Lotti, WG’82, profiled earlier).

Gloria Leporati seems to have balanced an interest in academics with a successful career in money management. She taught international finance at Bocconi University for five years after graduating from Wharton, and then, in 1987, was hired as an economist and Japanese portfolio manager at Gestiras, the investment arm of RAS (where she reports to Alberto Lotti, WG’82, profiled earlier).

Currently Leporati is responsible for Gestiras’ fixed income and foreign exchange rate investments. She has about $700 million under management, plus an additional $50 million in Asian equities. The rate of return for her largest fund is approximately 9.18 percent. “It’s been a very volatile year,” she says. “The value of our foreign currency holdings have been reduced … Even if we believe the lira is the best possible investment, we have to keep in the international markets.”

The job is clearly demanding in that it “requires the ability to screen, process and interpret an enormous flow of information,” she says. But all that is doable. What is stressful, she adds, “is people. I find managing a staff more difficult than dealing with economic variables.”

Leporati decided to come to Wharton back in 1980 because “she is and always has been a fan of the U.S., and I like math.” She is still in touch with friends and several professors from Wharton, and RAS recently sent several managers to the School’s executive education courses.

Unlike her boss, who is an avid soccer player, Leporati says she is “totally devoted to doing nothing. I might take up tennis again, but if I were asked to describe my favorite sport it would be to go to the seaside and lie down.”

When he first entered the fashion business back in the 1970s, says Isaac Douek, fashion houses tended to be poorly run, led by designers with few business skills and no professional managers to back them up.

Today, says Douek, the business has changed. Although the fashion industry slumped through a three-year recession in the early ‘90s and is just beginning to level out, most of the major houses like Valentino, Armani and Versace are professionally run and flourishing.

Douek himself mixes both fashion experience and a strong business background as president of Licensing and Development Group, a three-person, family-run consulting firm that specializes in licensing and franchising for fashion and brand names. He is also a consultant on the fashion industry for a large Japanese investment bank, and frequently lectures on business and fashion for universities.

Douek himself mixes both fashion experience and a strong business background as president of Licensing and Development Group, a three-person, family-run consulting firm that specializes in licensing and franchising for fashion and brand names. He is also a consultant on the fashion industry for a large Japanese investment bank, and frequently lectures on business and fashion for universities.

After he graduated from Wharton, Douek, who was born in Cairo and earned his undergraduate degree in engineering from the University of London, worked for BCG in Boston and then Milan. When BCG pulled out of Italy in 1974, Douek, after a short spell with an Italian clothing company called Marzotto, joined Valentino Couture as director of licensing and development. He set up licensing agreements in Europe, the U.S., South America and the Far East for eyewear, perfumes, cosmetics, ceramics and sportswear, among other products.

He left Valentino in 1981 and started LDG, first in Rome and later in Milan. He acts as a broker between fashion companies and/manufacturers/distributors.

Since most of the large fashion houses have their own licensing departments in-house, Douek typically works with smaller houses, defining their priorities and then contacting, and negotiating with, potential partners for licensing and franchising. He would like to expand his business to fashion firms in Europe and also to pharmaceutical companies in both Europe and the U.S.

Douek and his wife, whom he met in 1975 during a business trip to Beirut, have a son, 17, who attends the French school in Milan.

Milan is Douek’s choice of residence because it’s “where industry is located, and it’s more efficient, nearer to the heart of Europe. Take the car and you are in Switzerland or France in under two hours.” But he also likes Rome, “ for the tourism, the weather, and a better cost of living.”