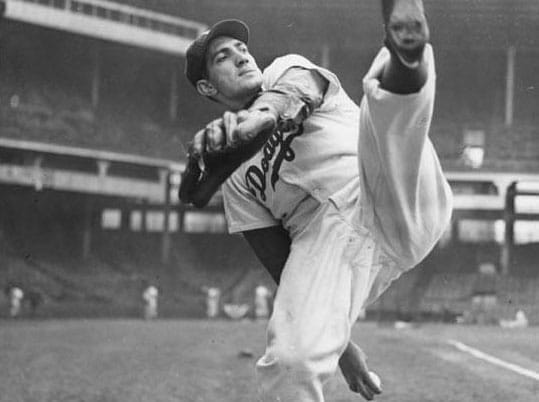

“Hum that pea,” Hall of Fame catcher Roy “Campy” Campanella urged Brooklyn Dodger pitcher Don Newcombe. But while Campy pushed Newcombe to go all out with his fastball, he often declared that another Dodger pitcher, little known Erv Palica, threw even faster.

“Newcombe throws peas,” Campy said. “But Palica throws peas with streamers.”

Seems absurd when you compare Newcombe’s and Palica’s careers. Palica’s major league win-loss record never reached .500. The legendary Newcombe, in comparison, earned three of baseball’s most prestigious awards: Rookie of the Year, MVP and the Cy Young. Until the Tigers’ Justin Verlander arrived, that feat stood for 60 years.

But in judging Palica’s hopping fastball, Campy wasn’t just talking through his mask. In 1950, Palica’s best year (13-8), he topped Newcombe’s strikeout percentage by a decisive margin. Newcombe struck out 11.8 percent of the batters he faced. Palica struck out 15.4 percent.

Ervin Martin Pavlicevich (his birth name) played a prominent role in what I have always considered to be the worst day in the history of American sports. Although the full realization didn’t hit me until many years later, I clearly recall that day’s inauspicious arrival. While devouring my customary Daily News report of a midseason Dodgers game during the 1950 season, I read the below words, the essence of a post-game talk between Chuck Dressen and sports writer Dick Young:

“I asked Dressen why he didn’t pitch Palica more. The little manager put his hand to his throat and said, ‘In big games, he chokes.’”

For me, that was the day this “choke” business began and forever embedded itself in the sports vernacular. “He choked” now spills from the lips of 40-ish flabbies like raindrops falling from a Cape Cod nor’easter. Puffy gutbags who have never laced up a pair of sneakers or bent over to field a ground ball are certain of their psychiatric insight into an athlete’s mind. They always know the real reason behind the loss: “He choked.”

During the 1951 season, when the Dodgers were in the process of squandering a 131⁄2-game lead and handing the pennant to the Giants, a Dick Young column began, “The tree that grows in Brooklyn is an apple tree.” The meaning of “apple” (as in an Adam’s apple enlarged enough to make you choke) had become such an integral part of the sports lexicon even an untutored sports reader recognized exactly what Young meant.

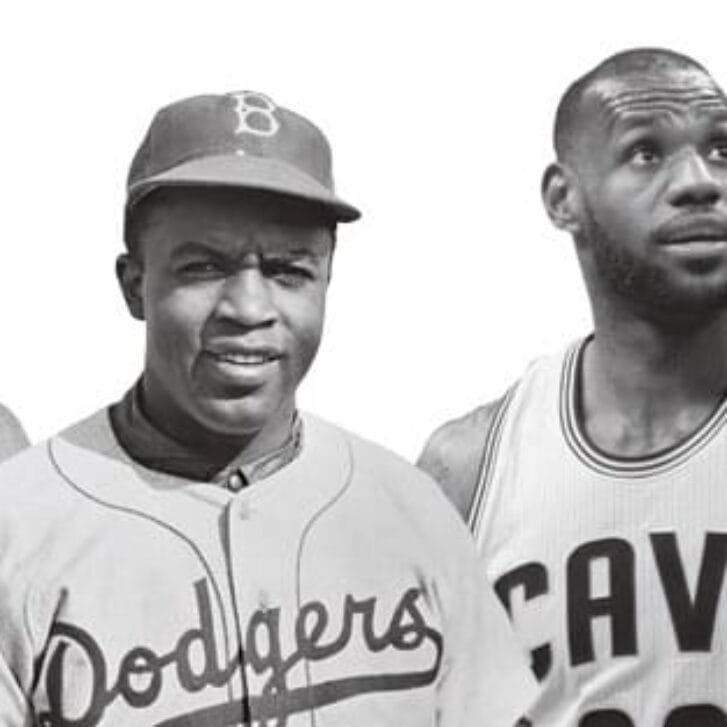

Yet, there are so many little things that go into a loss. Could the reason for the Dodgers’ collapse have been overconfidence? Nope. Laziness? Nah. Concealed injuries? Forget it. Young stood absolutely convinced there was only one reason: “They choked.” How come with all his behind-the-scenes knowledge, he never knew that the Giants had planted a spy in centerfield to steal the Dodgers’ signals? Did that secret information give Bobby Thompson an edge in hitting the winning home run off Ralph Branca’s fastball in the season’s final playoff game? Get serious, Branca choked.

Watch another “Worst Day in American Sports” for the author: when Bobby Thompson hit the “Shot Heard ’Round the World” against Ralph Branca on Oct. 3, 1951.

I’d always hoped this choking fixation would wear itself out and fade away. But after reading the May 17 issue of The New York Times Sunday Magazine, I look forward to hearing it applied not only to athletes, but also to business executives. The Times article, titled “Inside Chokes,” states: “Scientists at Johns Hopkins University decided to investigate what happens in the brain of a person who chokes.” (For an online version of the article, read “The Psychology of Choking Under Pressure.”)

Looks like it won’t be long before it becomes part of the conversation at America’s stockholder’s meetings when it’s time to explain how a CEO let the share price slide.