After more than 50 years of economic stagnation, Myanmar is opening its doors to investment from the outside world. It is being called “the final frontier,” with all the possibilities that phrase suggests. Yet many global business students are still overlooking or hesitating to even explore its potential, their entrepreneurial instincts curbed by a desire for a more secure career venue. I suggest they consider a Myanmar parallel: China.

The early stage in the economic rise of Myanmar is reminiscent of the emergence of China 20 years ago. As a potential magnet for business, China in the late 20th century was a precursor to Myanmar today.

In the early 1990s, business students were just starting to pay attention to China. By the mid-’90s, students were seriously weighing China’s economic potential. Yet throughout that decade, China remained a gamble. It was only in retrospect, after China’s business momentum became robust and sustainable, that its rise seemed inevitable.

In the early 1990s, business students were just starting to pay attention to China. By the mid-’90s, students were seriously weighing China’s economic potential. Yet throughout that decade, China remained a gamble. It was only in retrospect, after China’s business momentum became robust and sustainable, that its rise seemed inevitable.

Students of the earlier era who had correctly perceived China as a potential economic opportunity were congratulated by classmates for being farsighted. Today, students commonly study Mandarin as a second language in preparation for doing business with the Chinese.

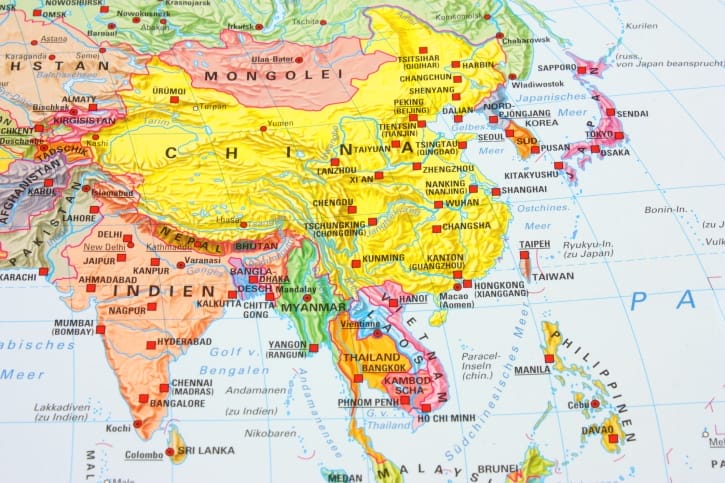

Now it is Myanmar’s turn as an infant economy to stand up, then walk, then run. As the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia, Myanmar once was the wealthiest country in the region. It has the potential to re-emerge as a regional powerhouse, with untapped agricultural and mineral wealth, a rich endowment of natural and human resources, and an enviable location between the world’s most populous countries, India and China.

Myanmar’s future—as was China’s—is connected to political and economic reform. It has such luminaries as democracy advocate and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein.

Yet at this stage, it is still a first-mover’s gamble. That is the beauty of it. While first-movers face fairly daunting odds—that comes with being first in anything—those who achieve success will reap rewards denied their more risk-averse peers. For hired guns, the risk is offset by Myanmar being one of the last remaining “hardship posts.” The U.S. State Department’s 2012 allowance for Myanmar’s Post Hardship Differential was 30 percent of basic compensation, higher than for any neighboring Southeast Asian country.

In negotiating for a dream job in Myanmar, a business school grad shouldn’t forget to mention the country’s poor infrastructure, periodic regional conflicts, seasonal hot weather and unreliable electricity. Of such talking points are comfortable salaries made.

If this all seems too good to be true, it might be. Time will tell. China was not seen as a golden opportunity, until it was. Success wears many disguises and only the prescient can spot it under wraps. But now is the time to start thinking about Myanmar as an opportunity.