We are all familiar with the tale of the little Dutch boy who saves the Netherlands from a flood by using his finger to stop a leak in the dyke. Today, we are all engaged in a similar exercise, trying to stem the electronic inundation of incoming emails. According to one recent study, the average executive received 101 business emails per day in 2013 (after spam filtering and excluding personal emails). In the C-Suite and the financial industry, the number is double or more from what I have seen.

In dealing with this flood of email, we need to be cognizant that emails are forever, and we need to develop a mechanism to think about each email we send.

Two recent legal cases highlight the risks of failing to appropriately consider the content of one’s emails.

The Dewey Case

The first of the two cases is the implosion of the white shoe law firm Dewey LeBoeuf, which is playing out in New York State Court. In the case, it is alleged that senior members of the firm’s management misstated financial statements and deceived lenders in order to hide the firm’s financial difficulties, to obtain loans and to cover up the firm’s failure to comply with financial covenants. Several parties have already pleaded guilty to a variety of charges and some senior executives are facing trial.

What are the “smoking gun” emails in that case? There are many.

There is an email from the chief financial officer in which he asks, “Can you find us another clueless auditor for next year?”

At least one of the executives seems to express remorse when he emails the CFO, “I don’t want to cook the books anymore… we need to stop doing that.”

(See this article from The Wall Street Journal for more examples.)

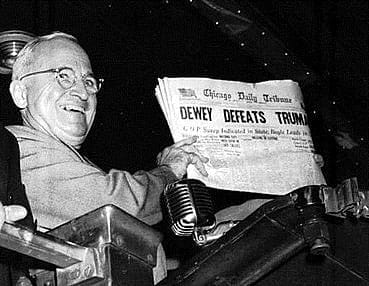

Dewey LeBoeuf is now in bankruptcy, a rather ignominious end for a law firm that bore the name of one of the most famous anti-corruption prosecutors of the mid-20th century. While the New York State Thruway is named after him, and Humphrey Bogart played a character modeled after him in the movies, Thomas E. Dewey is best remembered for the erroneous 1948 Chicago Tribune headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.”

It now appears that email has defeated Dewey.

Rural Metro

While we may have little sympathy for those accused of having “cooked the books” in the Dewey case, the case of Rural Metro, recently decided in the Delaware Chancery Court, raises different concerns. In Rural Metro, a company’s financial advisers were consulted on a sale of the company. In a stockholder suit, it was alleged that the board of directors breached its fiduciary duty in the conduct of the sale, and that that breach was aided and abetted by its two financial advisers. The board and one financial adviser settled, and the second adviser went to trial.

The court found that the financial adviser had aided and abetted a breach of fiduciary duty by the company’s board by artificially depressing the target’s valuation in supporting its fairness opinion. The Chancery Court pointed to the adviser’s own internal emails as some of the most damning evidence.

In one email, an investment banker responds to a draft analysis meant to support the fairness opinion by writing: “I thought we were going to try to reduce dcf (discounted cash flow)?” Was this an email designed to cook the fairness opinion books, or was this just a banker trying to reflect an earlier analysis that the discounted cash flow analysis should be lower?

On the eve of delivering the fairness opinion, a banker emailed one of his colleagues: “Lets [sic] make sure all bankers know (that the buyers) owe us big time. Should be first page of all pitch books.” Is this a banker trying to puff up his importance in his organization, or is this evidence of cooking the valuation books to favor one bidder?

The Chancery Court took this email to mean that the target company’s bankers manipulated the fairness opinion to the benefit of the buyers so that the bankers could be well positioned for future financing transactions.

Not the way to manage email.

The challenge in today’s world is managing the electronic flood of email in a responsible manner and not merely “leaf blowing,” a pejorative term used by one of my clients to describe the actions of some of his advisers: “You don’t really do anything, all you do is move the email from one person to the other, like my next door neighbor who has his gardener blow his leaves from his property on to mine.”

In the Dewey case, smoking gun emails helped to expose fraud; in Rural Metro, emails were used to establish improper intent on the part of a party. It is not clear that emails between two employees of the same company, written in haste over the course of a busy weekend, when taken out of their context in a deposition or court proceeding adequately reflect the motives of the employer-company. Who among us has not written a hasty email with a snide or cutting remark that if given the light of day would not fairly reflect our motives and views?

Bad email techniques can be destructive of good business relationship and lead to legal difficulties. Among the techniques used to manage email traffic are:

• Folders to categorize items

• Delivery delays. Do I really need to send this email to someone over the weekend? Or can I delay delivery until Monday.

Perhaps the most important technique to avoid email difficulties is to simply think for 10 seconds before hitting send. Ask yourself how it will look in hindsight. I think the email senders in Dewey and Rural Metro would say that that is time well spent.

Editor’s note: This blog post is intended as general information on the law and legal developments, and is not legal advice as to any particular situation. Under New York ethical rules, please note that this post may constitute “ATTORNEY ADVERTISING.”

The author’s firm represented Rural Metro in its subsequent bankruptcy proceeding.