Rush-hour bumper-to-bumper traffic has got to be one of the most agonizing experiences a person can go through. Okay — maybe not the most agonizing, but it’s certainly painful. The onslaught of cars exceeds highway capacity, and traffic slows to a crawl. How could a city accommodate more cars? An obvious solution is to widen the freeways; more capacity supports more cars. But I grew up in Toronto, which features an 18-lane freeway that cuts across the city. It still gets gridlocked.

In our daily lives as well as in our work, we’re often taught to think fast, act decisively, and tackle problems head-on. The downside is that we often charge forward by solving the most obvious problem. But the most obvious problem may not be the right problem to solve.

This is where “problem reframing” comes in. Reframing is about selecting the right version of a problem to solve. It’s about stepping back, challenging assumptions, and discovering the heart of an issue. In design-thinking terms, it’s about exploring the problem space before moving to the solution space. In our traffic scenario, what if the problem wasn’t how to accommodate more cars, but rather how to offer more transportation alternatives to people? Or perhaps the problem is reframed as how to reduce demand for freeway access. The problem definition changes the solutions completely.

A closer look at the problem can enable us to solve root causes over symptoms. The right framing helps us to innovate more and to create higher value for customers.

Companies such as Starbucks can credit reframing for their astounding growth. The original Starbucks premise was to sell high-quality coffee beans. The first Starbucks location, in Seattle, didn’t even feature seating. On a trip to Milan, CEO Howard Schultz noticed a peculiar coffee culture distinct from that in America — coffee was a ritual, and coffeehouses were communities. This prompted Schultz to reframe the problem-to-solve from “How could Starbucks provide high-quality coffee beans?” to “How could Starbucks become a place for customers to socialize and enjoy their coffee?” This reframe led to the creation of a “third space,” distinct from work and home, with Starbucks locations featuring warm interiors and comfortable seating and the proliferation of more than 30,000 locations worldwide.

Here are a few techniques to help reframe problems, adapted from Creative Confidence, by Tom and David Kelley, founders of acclaimed design firm IDEO and pioneers in design thinking.

Alter your focus or point of view by considering different stakeholders and their goals.

Schultz did this effectively when he saw the coffee experience through the customer lens and noticed a desire for a community space. Different stakeholders may have different goals. For example, Airbnb consists of guests and hosts. Each ostensibly have different goals; guests want a place to stay, and hosts want some extra income. However, both are often interested in community and a home-like experience. The differences and commonalities in goals enabled Airbnb to go beyond the immediate needs of each stakeholder, and Airbnb became an experience, not just a room with a bed for out-of-towners to sleep on.

Step back from the obvious solutions to explore alternatives.

A company I worked with offered coaching memberships for professionals. The memberships were cohort-based, which meant we had to get a certain number of memberships signed up to launch a cohort. However, we were behind schedule in memberships for the timeline needed. The team rallied around converting potential members who had inquired about the service. It’s a relevant and obvious solution. However, we stepped back and also considered other solutions. We looked at how to reach more relevant customers, who would see more value up front and would take less effort to sign up for memberships.

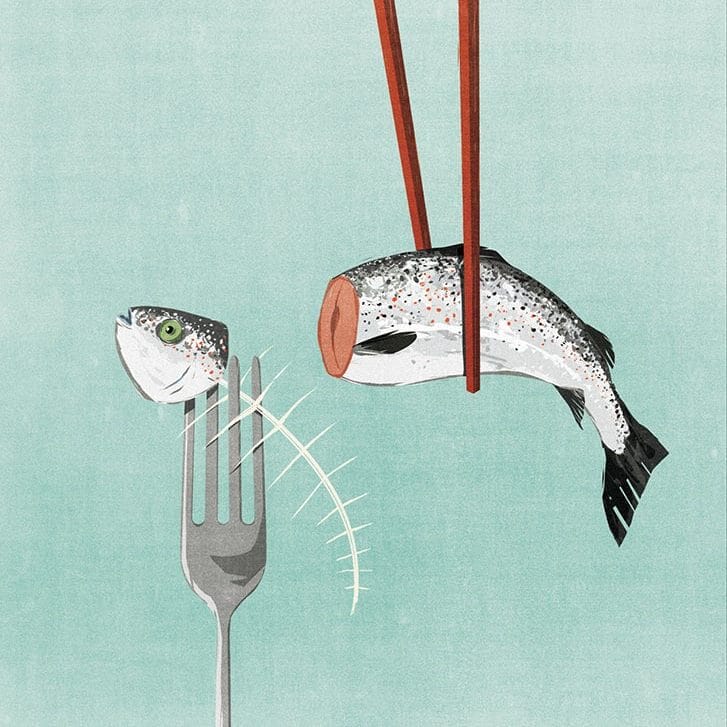

Ask “why” to uncover the deeper issues … and customer motivations.

Economist and professor Theodore Levitt famously said, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.” Dig deeper to understand the underlying needs and motivations of your customers or stakeholders.

Mason Park, a startup I co-founded with classmate Sudhanshu Juneja WG15, aimed to help brick-and-mortar retailers in the age of e-commerce. The original problem we sought to solve was declining foot traffic. Our original product relied heavily on retailer discovery and information to draw people into the store. However, we quickly learned that consumer behavior was changing permanently. The right problem to solve wasn’t “How can we help increase foot traffic?” but rather, “How can we help retailers thrive in the age of e-commerce?” This led to a product focus on e-commerce with features to emphasize the uniqueness of the retailers and brands. This enabled retailers to adapt to e-commerce but also to avoid competing on price and delivery speed, which large e-commerce retailers such as Amazon focus on. Retailers were also interested in adapting, as their real issue was business success. Foot traffic wasn’t the goal, but rather a means to their goals.

When we take the time to reframe problems, look beyond the surface-level symptoms, and explore alternative perspectives, we open ourselves up to fresh possibilities. We unlock the potential for breakthrough solutions that not only address the core needs of our customers but also differentiate us in a crowded market. So even in a bias-for-action world, it’s wise to pause and evaluate the issue at hand. With the right problem space defined, we can unlock innovations and set our businesses apart.

Timothy Kung WG15 has more than 15 years of experience as a product manager, most recently with Amazon. He is also the VP University Liaison of the Wharton Club of Seattle. He writes about the science of growth; check out Tim’s Newsletter on Substack.