When Mehmet Oz was 7 years old, his father took him out for ice cream.

When Mehmet Oz was 7 years old, his father took him out for ice cream.

Their destination was Peterson’s, a popular ice cream shop in downtown Wilmington, DE, which on that particular day was doing a swift business. Oz and his father got in line, and Dr. Mustafa Oz struck up a conversation with the boy in front of them. “So young man,” he asked, “what would you like to be when you grow up?”

“I don’t know,” the boy said. “I’m only 10.”

Oz remembers his father being just as perplexed by the boy’s answer as the boy was by the question. “My father turned to me and he said, ‘Don’t ever give me that answer,’” Oz says. “He said, ‘You don’t have to know right now what you’re going to do with your life, but you should always know the direction you’re headed.’”

Oz, WG’86, M’86, has never had a problem heeding his father’s advice. For as long as he can remember, Oz wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps—to be a surgeon. And today, that’s exactly what he is. As Director of the Cardiovascular Institute at New York Presbyterian Hospital and Vice-Chair and Professor of Surgery at Columbia University, Oz is one of the most accomplished and respected heart surgeons in the world. But that’s hardly all he is.

Because just as Oz always knew he wanted a career in medicine, he also knew he didn’t want just a career in medicine. Which is why this lifelong multi-tasker was one of the first students ever to come to Penn with the intention of simultaneously earning a Wharton MBA and a Penn M.D.

Oz likes a good challenge, but he certainly didn’t take on the dual-degree program just for kicks. He knew exactly why he wanted that MBA—and as his incredibly successful career bears out, he knew exactly what to do with it, too.

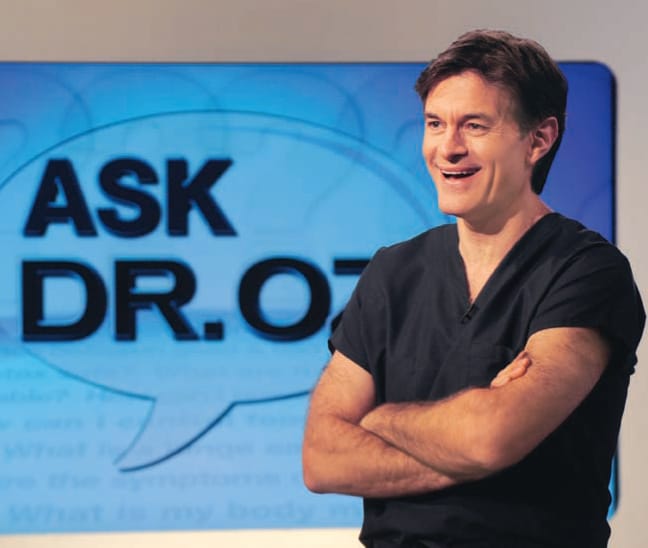

Today, Oz isn’t just a star surgeon. He’s also a star media figure—the author of five New York Times bestsellers, the host of his own radio show, a regular columnist in Esquire magazine and The Denver Post, one of the most popular guests in the history of “The Oprah Winfrey Show” (he’s appeared more than 50 times, generating ratings bumps with each appearance) and, since this fall, the host of his own hit daytime talk show, too. “The Dr. Oz Show” premiered in September and, with its groundbreaking mix of daytime talk and serious health discussion, promptly shot near the top of the daytime rankings. As of November, the two-month old show trailed only “The Dr. Phil Show” in the key demographic of women aged 25-54.

The show has succeeded, in part, because of Oz’s magnetic personality and, in part, because its focus on health research is unlike anything else on the daytime air. But according to Amy Chiaro, co-executive producer of the show, Oz’s success isn’t just about his good looks and charm.

It is also attributable, she says, to his startling work ethic—his drive to literally help Americans live better, healthier lives. “I’m pretty sure he doesn’t sleep,” jokes Chiaro, who left NBC News specifically to work with Oz. “He is a machine. I’ve never known anyone like him. I thought I was a multi-tasker. But nobody multi-tasks like Dr. Oz.”

Oz took some time out of his hectic schedule—at the time of our interview, the father of four was not only in the midst of taping the first season of his show, but also working on both a new book and the launch of a health-focused website—to chat with Wharton Magazine in late fall.

When did you know you wanted a career in medicine?

When did you know you wanted a career in medicine?

It was my calling. I knew it from a very early age. I played a lot of sports growing up, and like a lot of other athletes, I really enjoyed the challenge of using my hands. I just loved the idea of being in a field where you could [do that]. There’s a sense of immediate gratification to surgery for that reason. I also loved the fact that there was this opportunity to work in a field that you would never completely master. In medicine, you’ll never learn all there is to know.

[But] if you’re not a surgeon and you’re in medicine, your fundamental joy has to come from diagnosing illness. That’s a completely different mindset.After you graduated from Harvard, you enrolled here at Penn, where you began working toward both your Wharton MBA and your M.D. from Penn Medicine. How and why did you choose that path, and why Penn?

The joint degree was the reason I went to Penn. It was the only school I knew of that offered the joint MBA/M.D. At Harvard, you couldn’t do it. You couldn’t do it at Columbia, either. Wharton and Penn were very progressive, though. Not only was it possible to do it, but they had an entire operation geared toward helping you do it. I wanted to do both degrees and I wanted to do the classes at the same time. I really wanted to be able to go to school for both and not be an old man by the time I was done. Penn saved you a lot of years.

You always wanted to be a surgeon, though. So why get the MBA?

Because I realized that, in medicine, if you don’t understand how the hospital actually makes money, you aren’t going to be able to run the kinds of programs you want to run. Things like the cardiac program I run at Presbyterian—those are very, very expensive programs. You have to know the vocabulary of the hospital finance business. Otherwise, no hospital would ever let you handle all the money that it takes to run those programs. Right now I’m running what I believe to be the largest heart transplant center in the world, and my understanding of business is the reason why that’s possible.

The Wharton MBA program and the Penn Medicine M.D. program are difficult. How were you able to manage both at the same time?

I’ve always enjoyed doing two things at the same time, and that’s what I did at Penn. I could go in the morning to the clinic and treat diabetes patients, and then in the afternoon go learn about accounting and real estate transactions. After school, I guess some of my medical school classmates would go off and relax. Well, I just went across the street to Wharton. I think part of the reason why I enjoyed the Wharton side of things wasn’t just that the information I was learning was different, but that the culture was different, too. In business, you often hear the term “triage.” And though that’s a medical term, too, doctors don’t really do triage the same way. In business, you’re always doing triage, it seems. If you’ve got diminishing returns, you won’t find another investor, for example. It was a great experience for me to see both cultures.

Were there any other students doing the joint program at the same time as you?

There was one other person in my class. So there were just two of us. We were one of the first classes to do it, and before us there weren’t many students at all. It was like Noah’s Ark. They’d send you two-by-two. I remember getting involved in the Health Finance Group at Wharton, and that was a great experience for learning about the hospital business. Back then, very few doctors understood health care finance. Now, that’s really changing.

How different is health care today, as a business, than it was back when you were in school?

Well, it’s an entirely different field. It really is. I remember in school when we would be asking basic questions like, “How do you do accounting at a hospital?” There was really no way of doing it. We would say things like, “If I take a gauze pad off a shelf, who do I charge for that?” Now it’s more like, “How do I draw up a capital plan that makes sense for this hospital?” Things today are run much more like a business. It was sort of nice when you didn’t have to count all of the dollars and cents. Now, hospitals are all so streamlined, because they have to be.

When did that shift take place?

I can’t really put my finger on it. In the city of New York, what I do remember was when the bigger hospitals first started figuring out that they had some extra money to invest in marketing and advertising. That eventually started driving the smaller hospitals into bankruptcy. If you couldn’t do what the big ones were doing, you were going to go out of business.

What’s your take on the national health care finance debate? What’s the end-game here?

I think the big problem is that we’re all fooling around trying to answer the health care finance question. What we need to take care of are actual health programs. And you can’t legislate that, although of course Washington does have to deal with the issue of care for the uninsured. We recently did a program where we hosted the largest free health care clinic in the country. And though I’m happy we did it, it is quite frankly an embarrassing record to have for this country. The broader expense we have to deal with is the fact that two-thirds of our health care business is tied to chronic illnesses that are related to lifestyle choices. If we don’t do that, it doesn’t matter what we do with financing.

But isn’t convincing millions of people to change their habits even more difficult than trying to figure out how to pay for their care?

But isn’t convincing millions of people to change their habits even more difficult than trying to figure out how to pay for their care?

Yes, it’s a bigger challenge in some ways. But I don’t think it’s simply a matter of asking them to do this themselves. It’s a matter of helping them do it, too. For instance, if you don’t have walking and bike paths for people, well, they’re not going to go for walks. We need to help them make the right choices.

How did you make the leap from medicine to show business? And how did you end up as a guest on the Oprah show?

I grew up in the world of surgery, and I had a pretty conventional career at Columbia. Eventually, though, I began doing a fair amount of work in integrated medicine, because although I was in heart medicine, I began to realize that these people were going to need more than just a new heart to survive. They were also going to need a new outlook on life.

That process [of learning] was educational for me because I suddenly realized how much interest there is among the public in good health. It’s just that we in medicine weren’t talking about it enough. And after a few years of doing heart surgery and realizing that most people weren’t reading the same books [about integrated medicine] that I was reading, my wife said to me, “Well, let’s stop complaining and do something about it.”

You started talking and writing a lot about integrated medicine, and eventually your name landed on Oprah’s desk. You were invited to the show and went on to become one of her most popular guests. What was that experience like?

It was a wonderful adventure. As I like to say, I went to Harvard, and then Penn, and then Oprah U. [laughs].

When and why did you decide to do your own show?

The idea actually came from my wife, talking to Oprah. The shows [when I was on with Oprah] were doing well, and we realized there was an opportunity to do a bigger show with me hosting. It wasn’t a problem getting the financing set up, though if the economy had continued to go bad, then we may have defaulted. You have to make a commitment to do this kind of thing. It costs a lot of money. But at the end of the day, the economy turned around a bit, and the show is doing well.

What did you learn from Oprah about the television business?

One big message that was important for me to hear, as a male and father and surgeon—I had a trifecta there, where I want to fix every problem you face—was that women don’t always want you to fix their problems. They want you to hear their problems. That was a big transition for me.

Another big one was that, once you’re the host of the show, you have to let your guests be the star. But that doesn’t come naturally. It really doesn’t. You almost have to start thinking about it like a party. If you’re the guest at a party, you have to bring something—you have to bring some food, or some wine, or the ability to dance, or some humor. Something. If you’re the host, yes, you have to plan the party, but once the party begins, it’s not really about you. You have to help make the conversation happen, but you don’t have to be the center of attention.

I attended one of your tapings recently, and you were very relaxed on stage. Everything about showbiz and being on television just seemed to come naturally to you.

Yes, that part is the easiest for me. It really has been. The American public is smart. They know if you’re being who you really are or if you’re up there pretending. They can pick up pretty easily on non-verbal cues. It’s like the political process. If you’re going to host a television show, the public [had] better trust you. I think Oprah gave me a lot of trust with the public. You can’t abuse that. If you do, you won’t get it back again.

Ultimately, what do you hope that the show can accomplish?

I want to be able to have a conversation with America about health issues. If we can do that effectively, then I think we’ll have accomplished a big goal. A big part of that is treating the audience with respect. They can deal with some fairly sophisticated stuff, as long as you’re clear about it. We make sure our audience knows what’s going on, but we still do sophisticated, real stuff. We put all the pieces together for an experience that the audience finds thrilling. Because if the audience is not the No. 1 focus, they’ll know it. Oprah was the best at that—the audience is always No. 1.