The displacement of more than two million people in Darfur, in the Western Sudan, and subsequent deaths and rapes of hundreds of thousands there, has caused consternation and frustration by sympathizers all around the world about what to do.

The development and distribution of a new kind of stove may seem but a slight response, but Andrée Sosler, WG’08, executive director of the Darfur Stoves Project (www.darfurstoves.org), is convinced it goes to the heart of several problems.

“This attacks the situation on so many levels that I feel we are on the right track,” said Sosler. “It is environmental, social, about health and security. It is surprising how a seemingly incidental item like an efficient stove can be so multi-faceted.”

Even in refugee camps, women in Darfur must cook for themselves and their families—and that requires firewood. In their native villages, that was not much of a problem, but wood supplies near the crowded refugee camps—operating now for the better part of a decade—have become scarce. There are more people in such a small space than the land can support, so any forests nearby have become quite denuded.

Thus women and girls often have to spend the better part of a day, three to five times a week, looking for a tree that can provide that cooking wood. “That is when they are the most vulnerable to rape and assault,” said Sosler. “That threat was the original impetus for the Stoves Project.”

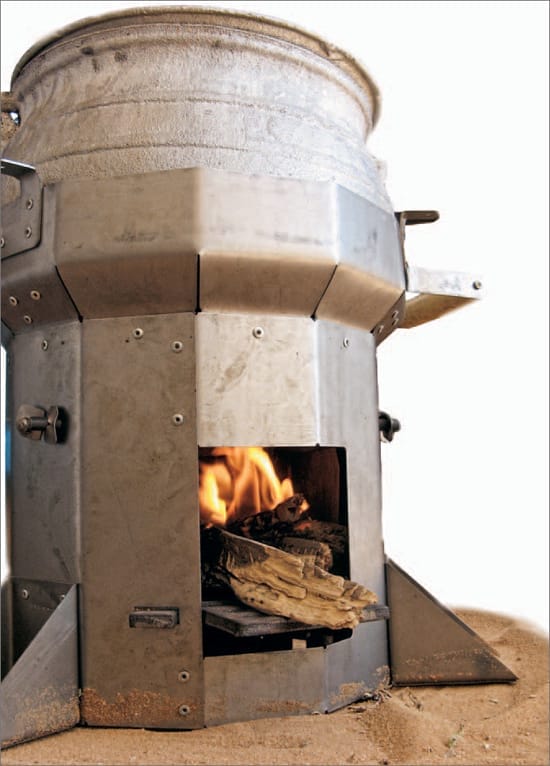

Ashok Gadgil, a professor of environmental technology at the University of California, Berkeley, where Sosler’s Darfur Stoves Project is based, who formerly developed a water purification device popular in underdeveloped areas, devised a more efficient wood-burning stove that fit the traditional stone-based fire areas and cookware of the Darfuris.

“Because of his water purification work, he was well known to the world aid community, and he was happy to help out with the Stoves Project,” said Sosler. She said that Darfuris use round-bottomed pots and most stoves are designed for flat bottoms. Through trial and error, too, Gadgil and his engineering team were able to make the stoves easier to transport and more efficient, so the women needed far less wood—in some cases only a quarter of what they had used before.

In the places where her project has been able to distribute the stoves, said Sosler, as many as 80 percent of the Darfuri women now do not go out to forage for wood at all.

In addition, said Sosler, the new Darfur stoves provide an environmental and health boon. She said that as many as three billion people around the world cook meals, primarily indoors, with open fires using wood or coal or similar substances like in Darfur. As many as two million of them may die from exposure to that kind of smoke.

“The more that we can reduce that type of emission through more efficient stoves, the better that would be for the environment as well,” she said.

Currently, the project expects to be able to finance and make about 25,000 stoves in 2011. They each cost about $20 for raw materials, manufacturing and assembly, most of which is funded through donations, though Sosler said some small part of the cost is actually borne by the women themselves. The parts are primarily made in India and then assembled in Darfur, where about a dozen men are employed to do so, another small beneficial offshoot of the project.

Currently, the project expects to be able to finance and make about 25,000 stoves in 2011. They each cost about $20 for raw materials, manufacturing and assembly, most of which is funded through donations, though Sosler said some small part of the cost is actually borne by the women themselves. The parts are primarily made in India and then assembled in Darfur, where about a dozen men are employed to do so, another small beneficial offshoot of the project.

Sosler came to Wharton after working for five years in New York-based non-government organizations—much of them doing work in Africa—following her international development degree from Brown University. After Wharton, she worked for a year doing consulting for a private development group in Rwanda, but said she wanted to get back into NGO work. She was attracted by the movement of “venture philanthropy” in Silicon Valley and purposely looked for a job on the West Coast that would feed on that.

“It is like venture capital in that the donors look for definite results–maybe not in monetary return, but in social return,” she said. “That appealed to me. One of the things business school taught me is the inefficiencies in international development. The Darfur Stoves project gives it focus.”

She said that she feels there is an increased focus at Wharton in social entrepreneurial issues. “I am glad Wharton has taken an interest in the area,” said Sosler, who as a student was co-president of Wharton Social Impact and helped organize a national conference on those issues that happened last year, after she was already in Rwanda. She has recruited at least five Wharton graduates to be on her board, she said, and hopes more will be interested in the project as it proceeds.

Though Darfur will continue to be the focus of the Stoves Project, she and her board are looking at expanding the project to other areas–perhaps neighboring Chad, which harbors many Darfuri refugees.

“Technology can solve social ills,” said Sosler. “And sometimes that is how the overall situation can improve.”