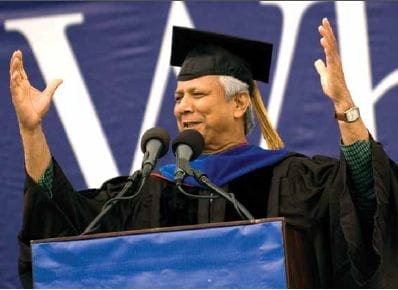

The founder and managing director of Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank, citing what many describe as the sorry state of much of today’s banking industry, urged graduates to “do the opposite of what conventional banks do” as they look to build satisfying, successful and meaningful careers for themselves.

“They go to the rich,” he said of the banking industry. “They go to men. They establish themselves in the center of cities. They require collateral and legal documents. They are owned by rich people.”

Grameen Bank, by contrast, is thriving, with a nearly 100 percent repayment rate, by doing precisely the opposite: lending to poor women in tiny villages who have no collateral. “Sometimes reversing something, turning things around, works beautifully,” Yunus said.

Yunus started what became Grameen Bank in 1976, believing that small loans to the world’s poorest people could lift them out of poverty. Grameen Bank (“grameen” means “village”) has since spawned a host of microfinance programs that lend small amounts of money to poor people to start businesses, including those that sell crafts, food, and services. It now has more than 7.5 million borrowers, 97 percent of whom are women, and has lent more than $8 billion with a near 100 percent repayment rate.

In his speech to Wharton MBAs, Yunus argued that poverty is “created by the institutions we have built and the concepts we have designed. Human beings are not money-making machines,” Yunus said. “They have selfish and selfless (characteristics) in them.” He urged the MBA class to work toward creating something he called “social business,” a model that focuses first on helping the world rather than taking from it.

“There is so much to be done,” Yunus told the graduates. “If you put your mind to it, there is no reason we cannot address poverty, environmental degradation, you name it. That is a challenge for you. You can create your own world. What kind of a world do you want to create?”

In his commencement address, Wharton Dean Thomas S. Robertson described the roller coaster ride graduates have witnessed in the business world during their short time at Wharton: The S&P 500 rose to its historic high of 1,565 in October 2007 Ñ then fell to a 12-year low of 677 in March 2009.

Somewhat less obvious has been the extraordinary acceleration of technological change over the past few short years. Much of the technology now taken for granted was still quite rare back in 2005; it is now ubiquitous, Robertson said. Facebook was launched in 2004. YouTube arrived in 2005. Twitter is barely three years old; the iPhone just two. Kindle arrived in 2007, and Hulu opened to the public in 2008.

“These new technologies have shattered many of the business models that were profitable not so long ago,” Robertson said, citing the newspaper business, the recording industry, and other media companies. “While many decry the falling away of É old business models, this clears the way for you. You are handed the challenge of creating new business models that will drive the next wave of growth.”

He closed with a reflection on leadership today. “Society has changed and it will continue to change, as change is the only constant in life. But for now, ostentatiousness is out and greed is so last year. Social responsibility and community mindset are in. The imperial CEO is out; the entrepreneur is in,” Robertson said.

Robertson shared Wharton School founder Joseph Wharton’s belief that business education should find “solutions to the social problems inherent in our civilization,” that its leaders should be community builders and leaders who are responsible to society’s shared needs.

“That is our hope for you,” Robertson told the graduates. “We have confidence in you. We expect great things from you. From those to whom much is given, much is expected.”

Earlier that day, at the Undergraduate Division graduation ceremony, new graduates celebrated under umbrellas and gray skies.

Student speaker, Ravi Naresh, C’09, W’09, a student in the Huntsman Program in International Studies & Business, also described the dramatic changes this year’s graduates have faced since arriving at Wharton four years ago, changes that, for many, have meant job offers that have slipped away with Wall Street’s fortunes. But these changing realities have also brought the graduates greater resiliency, creativity and “above all we have learned to solve problems,” Naresh told classmates.

Wharton Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics and Management G. Richard Shell, in accepting the David Hauck Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, encouraged graduates not to worry about what they do right after college. Assistant professor Shane Jensen also received the Hauck Award.

“The important thing is to figure out what you like and don’t like in the world of work,” Shell said. “So consider the next few years as a graduate program in an institution called ‘The School of Life.’ ” The most prestigious positions on Wall Street will feel oppressive to someone whose passion is teaching or entrepreneurship, he said. “And even if you end up waiting on tables for a little while, you may discover that you are passionate about delivering perfect service to customers. Once you really ‘get’ that, you can set your sights on becoming the president of the Four Seasons Hotel Group.”

Shell, a negotiation expert and author of the book, The Art of Woo: Using Strategic Persuasion to Sell Your Ideas, told graduates that successful negotiations are all about relationships. “There is no negotiation problem that cannot be fixed by a good relationship,” he said. “And few negotiations can survive a bad relationship. So treat people well, give them more than they expect, and they will give you in return, over your lifetime, more than you could ever achieve any other way.”