There is a sign on the wall behind Jon Huntsman’s desk in the executive offices of $5.2 billion Huntsman Corp. in Salt Lake City, Utah. It reads: “The greatest exercise of the human heart is to reach down and lift another up.”

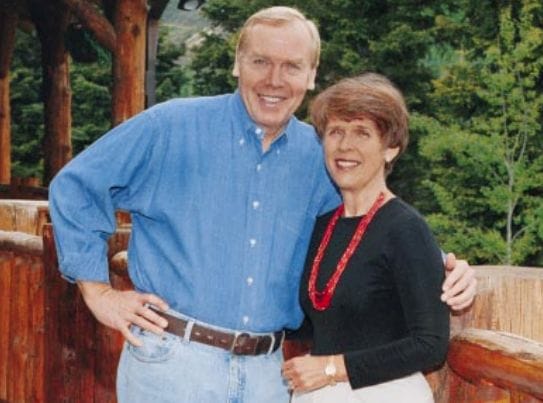

“Right after we were married and Jon was earning about $225 a month, I noticed that $50 was missing from every paycheck,” recalls Karen Huntsman. “I realized he was giving $50, anonymously, to one of the families in our neighborhood who Jon thought needed extra help. It taught me early on that if you don’t learn to have a charitable heart when you have nothing, you will never learn it when you have a lot. Jon has always wanted to make a difference in people’s lives.”

Most members of the Wharton community now know about Jon Huntsman’s latest gift to the Wharton School — $40 million, donated in May 1998, in unrestricted funds. It is the largest gift ever made by an individual to a business school.

And many in the business community know of Huntsman’s extraordinary success in founding the largest privately-held chemical company in the U.S. and building it into a $5.2 billion global enterprise with 10,000 employees and multiple locations worldwide. His rise from a manufacturer of plastic egg containers to head of a company with billion-pound world class petrochemical, plastics, rubber, textiles and packaging facilities has been chronicled in publications ranging from Forbes and the Financial Times to the Wall Street Journal and New York Times.

But few know about the man and the family behind the $40 million donation. Indeed, this is just the way the Huntsman family likes to give: with little fanfare, with great generosity and with a sincere feeling of gratitude to the people and the institutions who have made a difference in their lives.

In fact, the biggest long-term benefit to Wharton may not be financial; rather it may be an infusion of the spirit that animated this donation. What is the path that leads to, and the philosophy behind, a gift of this sort? Jon Huntsman’s childhood offers few hints of the distance he would travel on his way to becoming one of the country’s most successful entrepreneurs. His early years were, in Huntsman’s own words, “a time of difficulty and of struggle.” His father, A. Blaine Huntsman, started out as a rural schoolteacher in Blackfoot, Idaho. “We lived in subpar housing with no inside plumbing for almost four years of my life,” Huntsman says. When Jon was six, his father became an officer in the U.S. Navy and moved the family to a naval air station in Pensacola, Fla.

Jon Huntsman’s childhood offers few hints of the distance he would travel on his way to becoming one of the country’s most successful entrepreneurs. His early years were, in Huntsman’s own words, “a time of difficulty and of struggle.” His father, A. Blaine Huntsman, started out as a rural schoolteacher in Blackfoot, Idaho. “We lived in subpar housing with no inside plumbing for almost four years of my life,” Huntsman says. When Jon was six, his father became an officer in the U.S. Navy and moved the family to a naval air station in Pensacola, Fla.

After World War II ended, Blaine Huntsman returned to teaching school in Idaho. The years at the naval air station, however, had changed both his ambition and his expectations. “He was never again satisfied with life in rural Idaho,” Huntsman says. At age 42, the elder Huntsman made another move, this time to pursue a doctorate in education at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. He would eventually become superintendent of schools in the neighboring community of Los Altos.

While Blaine Huntsman spent three years getting his doctorate, the Huntsman family — including Jon’s mother Kathleen, his older brother Blaine, Jr., WG’68, and his younger brother Clayton — lived in cramped Stanford student housing on $120 a month from the GI Bill. Jon, at age 14, worked after school and on weekends to pay the family’s medical bills and car maintenance. “It was a very, very tough battle for a family of five,” Huntsman recalls.

Yet these hard beginnings forged something that a life of privilege sometimes misses, he notes. “Those early years developed the framework for tough competitiveness. My childhood exposed me to the hardships and heartaches of life. It was good for me. And I didn’t know I was poor. I was happy and grateful for what I had, and always appreciated what people did for me.”

Huntsman remembers his father as a stern disciplinarian, but also as someone who was “trying to get himself ahead in life.” Years after the elder Huntsman’s death, Jon Huntsman can look back at his childhood with “a sense of gratitude and thanksgiving because I knew how far I had come in my life. Except for the grace of God and my father’s efforts to get ahead, I might be back in a humble rural setting struggling to make ends meet.”

In her own way, Huntsman’s mother had as much of an influence on her middle son’s character as his father. Before her marriage, Kathleen Robison Huntsman had been a missionary for the Mormon church in the backwoods of Virginia and North Carolina. The early years of her marriage and motherhood were “an economic struggle that made everyday life difficult,” Huntsman says. “But she always had immense love for her three sons. I never heard her say an unkind word about anyone.” On her tombstone in a cemetery in Fillmore, Utah, are etched words that show how clearly the Huntsman family has always sought to take hardship and transform it into opportunity: “Sweet Are the Uses of Adversity.”

That phrase, Huntsman says, “epitomizes everything I think about my life because the tougher and more difficult life’s journey, the more rewarding and fulfilling it can be when you achieve something you were not expected to achieve.”

Huntsman has great respect for those who, like his parents, moved across the country in search of better lives for themselves and their families. His ancestors on both his mother’s and his father’s side were part of a pioneer group that had followed Mormon leader Brigham Young out West in the mid 1800s, eventually settling down and starting farming communities in Utah. Huntsman’s great-great-grandfather was Parley P. Pratt, one of the first Mormon apostles under Joseph Smith in 1835.

“These were people of great determination, great grit, and firm belief in their God and religion, and in the things that bring integrity and honor to their lives,” says Huntsman. “My heritage gives me a deep sense of pride and gratefulness.” When Huntsman was a high school senior in Palo Alto, he was asked by the school principal to attend a recruiting session for Wharton, a place Huntsman had never heard of. Harold Zellerbach, W’17, then executive vice president of Crown Zellerbach Corp., was the recruiter; Dr. Ray Saalbach, Penn undergraduate admissions officer, was also at the meeting.

When Huntsman was a high school senior in Palo Alto, he was asked by the school principal to attend a recruiting session for Wharton, a place Huntsman had never heard of. Harold Zellerbach, W’17, then executive vice president of Crown Zellerbach Corp., was the recruiter; Dr. Ray Saalbach, Penn undergraduate admissions officer, was also at the meeting.

“It was a milestone in my life,” Huntsman remembers. “I had never heard of Wharton or Penn, but both Zellerbach and Saalbach were very gracious. Zellerbach said, ‘Jon, you would be a wonderful businessman. You meet people well and you interact well with strangers.’ I told him I had never been East in my life.”

“It was a milestone in my life,” Huntsman remembers. “I had never heard of Wharton or Penn, but both Zellerbach and Saalbach were very gracious. Zellerbach said, ‘Jon, you would be a wonderful businessman. You meet people well and you interact well with strangers.’ I told him I had never been East in my life.”

Huntsman accepted the scholarship offer: $1,500 a year from Zellerbach and another $1,000 from the Northern California alumni club, arranged for with Zellerbach’s help. Between waiting on tables in sorority houses and delivering flowers in West Philadelphia, Huntsman made his way through Wharton.

That $10,000 investment by Wharton alumni in the 1950s proved to be money well spent. Huntsman was senior class president in 1959, president of Sigma Chi fraternity and the Kite and Key Club, and recipient of the 1959 General Alumni Society Award of Merit for leadership in undergraduate activities as well as the prestigious “spoon” award for the class of ’59. Huntsman also won Sigma Chi’s highest award that year — the International Balfour Award, among other honors.

“I was the product of rural public schools, yet I was always very much accepted at Wharton. I was always treated with respect and dignity,” Huntsman says. “I loved the interaction with people of different backgrounds. It’s a complete education, the best undergraduate and graduate education available, and it offers such a remarkable network afterwards in the business and financial world.”

When he announced his gift to Wharton last May, Huntsman credited the school with being “the place that got many of us started, the place that provided a balanced education to make us into what we are today. We can never forget those roots and the critical and meaningful role they have played in our lives.” At Huntsman Corp. headquarters, the office of the chairman on the third floor presents visitors two striking images. One is a panoramic view of Salt Lake City; the other is a bronze Remington statue of cowboys running at full gallop. The statue is blanketed with what may qualify as the world’s largest collection of beanie babies, arranged and rearranged depending on which grand-child visited last.

At Huntsman Corp. headquarters, the office of the chairman on the third floor presents visitors two striking images. One is a panoramic view of Salt Lake City; the other is a bronze Remington statue of cowboys running at full gallop. The statue is blanketed with what may qualify as the world’s largest collection of beanie babies, arranged and rearranged depending on which grand-child visited last.

The office is vintage Huntsman: a place where business gets done but where Jon and Karen Huntsman’s nine children and 37 grandchildren are always welcome and where the founder’s personal philosophy is as much a part of the corporate culture as the 20+ billion pounds of chemicals, plastics and packaging materials produced every year.

The company dates back to 1970, when Huntsman and his brother Blaine raised $300,000 in seed money plus $1 million in venture capital funds to start Huntsman Container Corp., the precursor to Huntsman Corp. Among the company’s notable successes was the use of polystyrene to make the “clam-shell” containers used for McDonald’s Big Macs.

In late 1970, Huntsman left the company to serve in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare and then as Special Assistant and Staff Secretary to the president of the United States in the White House. He returned to Huntsman Container Corp. in 1972, transferred the business to Salt Lake City, and spent the next few years overseeing the development of 80 new kinds of polystyrene packaging.

In 1982 he founded Huntsman Chemical Corp., renamed Huntsman Corp. in 1994 after the purchase of Texaco Chemical Co. Following a series of well-timed acquisitions and/or expansions, Huntsman Corp. today makes products that are found in everything from outdoor furniture, toys, clothing, medical devices, personal care supplies, detergents, textiles, batteries and carpeting to pharmaceuticals, car waxes, paints, appliances, computers, televisions, cameras and bicycle helmets, to name a few of the end uses recognizable to consumers.

Throughout nearly three decades of company growth, Huntsman says that he “has always erred on the side of my heart … We’ve written our own set of rules. We don’t follow bureaucratic guidelines established by someone else. They are golden rules that we hope others would apply to us if we were in a similar position.

“It doesn’t mean, however, that we are not tough-nosed businessmen. It doesn’t mean we won’t go in and cut the toughest deal possible.”

Indeed, press accounts of Huntsman Corp.’s business dealings over the years suggest a CEO who is considered one of the industry’s shrewdest and most successful negotiators. His ability to acquire undervalued assets during cyclical downturns in the chemical industry — then pare costs and run the acquired plants at full or near-full capacity — has led to a huge production base acquired at a fraction of replacement cost. Huntsman Corp.’s biggest acquisitions have come from competitors like Texaco Corp., Shell Oil Co., Hoechst A.G., Mobil Oil and Monsanto.

Along with an aggressive acquisitions strategy and an impeccable sense of timing is the Huntsman style, which includes personal attention to major clients and a sincere concern for those on the other side of the bargaining table.

“We have some of the most creative business arrangements in the history of America, the most interesting methods of acquiring companies,” says Huntsman, who has been known to place top executives of an acquired company on the Huntsman Corp. board, make a donation to their favorite charity and/or carry over their existing retirement and vesting credits. “And we have an extremely high return on equity and a very high economic value added to our businesses because of that creativity. We’ve acquired 31 companies since 1982, more than anyone else in the chemical industry.

“All of these deals have been done differently and they have all been home runs. The reason is that we make them into home runs. We are able to negotiate deals that are win-win situations for everyone — employees, customers, selling companies and the community.” Jon Huntsman’s business and philanthropic activities over the past decade have brought him into contact with a wide range of world leaders. Three years ago, because the Huntsman family is among the largest contributors to Catholic community services in the U.S., he was invited to meet with Pope John Paul II in Rome.

Jon Huntsman’s business and philanthropic activities over the past decade have brought him into contact with a wide range of world leaders. Three years ago, because the Huntsman family is among the largest contributors to Catholic community services in the U.S., he was invited to meet with Pope John Paul II in Rome.

During a forum with leaders of the chemical business in Tel Aviv, Israel, he met with then Prime Minster Yitzhak Shamir. In 1989, he spent three days visiting Princess Diana and Prince Charles, with whom he served on the board of United World Colleges, at the royal family’s summer home in Highgrove.

This past year, he hosted former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Robert Kocharian, President of the Republic of Armenia, at his family’s 110-acre retreat in Deer Valley, 30 miles outside of Salt Lake City.

Yet for all his worldly connections, Huntsman seems most comfortable, and most passionate, when talking about his family and his employees.

Indeed, in the case of Huntsman Corp., the term “family business” has a wide application. In the early years of the company, says Karen Huntsman, “our family vacations were typically spent visiting a plant or meeting with employees … Jon skipped the conventions attended by other industry executives in order to focus on building a business, being a father and working with the church.” Today, several of the Huntsman children are directly involved in the company. Jon Huntsman Jr., 38, C’87, is vice chairman of Huntsman Corp.; Peter, age 35, is president and COO of Huntsman Corp.; David, age 30, C’92, is vice president, Huntsman Polymers Corp.; Paul C., age 29, was product manager of the Olefins Group, Huntsman Corp., before leaving to attend Wharton this fall; son-in-law James Huffman, WG’96, is vice president, corporate strategy, Huntsman Corp., and son-in-law Richard Durham, W’87, is president and CEO, Huntsman Packaging Corp.

Today, several of the Huntsman children are directly involved in the company. Jon Huntsman Jr., 38, C’87, is vice chairman of Huntsman Corp.; Peter, age 35, is president and COO of Huntsman Corp.; David, age 30, C’92, is vice president, Huntsman Polymers Corp.; Paul C., age 29, was product manager of the Olefins Group, Huntsman Corp., before leaving to attend Wharton this fall; son-in-law James Huffman, WG’96, is vice president, corporate strategy, Huntsman Corp., and son-in-law Richard Durham, W’87, is president and CEO, Huntsman Packaging Corp.

Employees, for their part, belong to a business whose base pay is competitive with similar companies in the petrochemical industry but whose family-oriented fringe benefits include scholarships for their children. Every employee in the company — from the president on down — receives the same holiday gift, which in the past has included family trips to the Caribbean and 35-inch television sets.

The Huntsman Corp.’s emphasis on safe working conditions has resulted in zero fatal accidents over its nearly 30-year history, despite what are often massive 5,000-acre sites dominated by heavy machinery and equipment. “Safety for us is so critical,” Huntsman states. “Employees here know that for me to lose one of them would be like losing one of my own children. I think the fact that we can focus on safety issues no matter what the cost, and not have to worry about quarterly earnings and dividends, gives us a very different sense of direction. The employee is the object of our attention, not earnings per share.”

The Huntsman way has resulted in a company with very low turnover, staffed with employees “who feel a tremendous amount of loyalty,” says Huntsman. But loyalty, he notes, “is a two-way street. Our employees have made me what I am today. I owe them an enormous amount because I could never have done this without them. I’m not a scientist and yet we have incredible R&D facilities. We are a very high-end scientific research company in the world of petrochemicals and chemical engineering. We have more than 2,000 different products that we produce from very sophisticated chemicals. To do all this you need unique and varied talents. I have the gift of extraordinary people around me.” To have built a $5.2 billion company, to be recognized throughout the industry as a brilliant entrepreneur and a responsible corporate citizen, one would think Huntsman had business role models from whom he drew inspiration or, at the very least, strategy. He doesn’t. “I’ve admired many men and women but I can’t think of anyone who is a role model,” he says. “A lot of business people get caught up in bureaucracy. They don’t make much of a difference … They aren’t attempting to change the world or help the needy. You don’t see much creativity at the executive level …”

To have built a $5.2 billion company, to be recognized throughout the industry as a brilliant entrepreneur and a responsible corporate citizen, one would think Huntsman had business role models from whom he drew inspiration or, at the very least, strategy. He doesn’t. “I’ve admired many men and women but I can’t think of anyone who is a role model,” he says. “A lot of business people get caught up in bureaucracy. They don’t make much of a difference … They aren’t attempting to change the world or help the needy. You don’t see much creativity at the executive level …”

For role models, Huntsman turns elsewhere. High on his list is his wife, whom he first met when she was 12 and he was 13. “We have gone through serious health problems and other struggles in our life, but we have taken each opportunity to turn these problems into learning experiences,” Huntsman says. “Throughout it all, Karen has always been articulate and disciplined. She has been a great cheerleader for me, and she has always looked for my best qualities.”

The medical community is another place that Huntsman turns to for role models. “The astronauts of the 1970s and 1980s were heroes then,” he notes. “Today my heroes are the people who are working on finding a cure for cancer.”

In 1995, Jon and Karen Huntsman donated $100 million to the University of Utah to establish the Huntsman Cancer Institute, with a focus on discovering the genetic factors that lead to cancer. Both of Huntsman’s parents died of cancer and Huntsman himself has been treated for prostate and mouth cancer.

Indeed, in many ways, the secret of the Huntsmans’ generosity seems to lie in relationships to others. From the porch on the West side of their home in Salt Lake City, one can look out and see the family’s impact on a city to which it feels such close ties: the Huntsman Cancer Institute, the battered women’s shelter funded by the family and named after Huntsman’s mother, the University of Utah Jon M. Huntsman Center basketball arena and a major children’s hospital. Not visible in that broad sweep are two homeless shelters and a food bank that the Huntsmans have helped fund in downtown Salt Lake, and the law library at Brigham Young University to which the family contributed $5.5 million in honor of a friend and former Mormon church president.

In a wooded area off to the side, one can just barely see the ongoing restoration of the old Huntsman Hotel, a pioneer establishment built by ancestor Gabriel Huntsman in 1872 — a reminder to the present-day Huntsman family of their deep roots in Utah and the Mormon Church.

These vistas don’t take into account the many hundreds of smaller donations Huntsman has given to people who are facing a particular crisis in their or a family member’s life. This year alone, the Huntsman family will donate approximately $60 to $70 million to charities and individuals (exclusive of the gift to Wharton).

Nor do they take into account places like Armenia, where since 1988, the family has spent close to $18 million to rebuild whole towns after a major earthquake left nearly one-third of the country homeless. The effort is ongoing, buttressed by a Huntsman Corp. factory — one of the largest in the former Soviet Union — that makes reinforced concrete. The family has also contributed to flood relief in Thailand and India.

“We have facilities in most of the countries of the world, especially throughout Asia,” Huntsman says. “If I know that a particular area needs help, and I know that it’s a really unusual situation where chances are nobody else will be there to assist, then we get involved … We are our brother’s keeper. The Bible is a wonderful resource to always remind us of our obligation to others.”

Huntsman today is described as one of the country’s most noted philanthropists, a recognition which, like other accolades, leaves him slightly embarrassed. He donates money to individuals and to institutions, he says, not for acclaim, but for the joy it gives him to help others.

“I feel an incredible peace of mind and sense of accomplishment by sharing wealth with another individual or an institution. That’s what life is all about. It’s as simple as that.” Jon Huntsman has been a member of Wharton’s Board of Overseers since 1985. In 1997 he and his family donated $10 million to endow the Huntsman Program in International Studies & Business, the leading international management program of its kind. His son, Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., is a trustee of Penn.

Jon Huntsman has been a member of Wharton’s Board of Overseers since 1985. In 1997 he and his family donated $10 million to endow the Huntsman Program in International Studies & Business, the leading international management program of its kind. His son, Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., is a trustee of Penn.

Given his close ties with the school over the years, what does Huntsman see as Wharton’s mission for the next generation of business leaders?

Unlike other educational institutions, he says, Wharton “focuses on the individual. I’ve always been proud of the fact that to get into Wharton, there is not one overriding condition that determines a person’s entry or success path. What is most important seems to be the completeness of the individual, not how he or she scored on a test.

“Wharton has spawned some of the great young entrepreneurs in the world today, and offered a balanced education to thousands of men and women. When they leave Wharton, they need to remember what they gained here in terms of education and social development, all the skills and abilities that were learned both in and out of the classroom. Our students who go forth to serve the world must recall the time and place that shaped their destiny and helped them attain their highest objectives …”

For the school’s part, Huntsman says, “I would hope that Wharton never forgets that the individual personality, the individual sense of purpose and integrity, are far more important than one’s computer skills or grade point average.

“I hope that many of my grandchildren will go to Wharton,” he adds. And when they do, “I am sure they will find that Wharton has continued to maintain its high academic standards and its ability to attract people from all around the world who have the potential for greatness or goodness, either one. Hopefully, the two will coincide.”