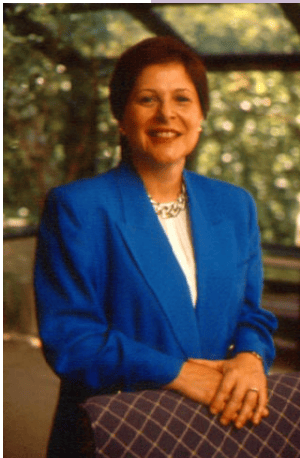

Last summer, Janice Bellace received an invitation from the government of the Ukraine to participate in a seminar on labor and employment law. As professor of legal studies and management at Wharton and an expert on multinational labor relations and comparative labor law, Bellace would be part of a team whose mission is to help this newly independent country write its own labor law code.

The same week the Ukraine invitation arrived, Bellace, who is also deputy dean of the Wharton School, held a meeting with administrators to discuss the Wharton Curriculum Navigator — a proposal to provide MBA students with new levels of online course information in a format that would allow cross-referencing of relevant data in such areas as scheduling, faculty expertise and course readings. “The Europeans have a good word for this — ‘transparent’,” says Bellace. “The information was always there, but it was hidden. This new program would make it transparent, easier for first-year students to access.”

For Bellace, the Ukraine and the Navigator are a reminder that, like most academic deans, she is constantly juggling two roles — high-ranking administrator and legal studies scholar. Her credentials to manage this dual career challenge are impressive:

On the administrative side, Bellace brings to the job a greater familiarity with the Penn community than any of her predecessors. She earned her undergraduate and law degrees from Penn and Penn Law School in 1971 and 1974, respectively, and has been on the Wharton faculty for almost 20 years, first as a lecturer in the Legal Studies Department (1977), then an assistant professor (1979), associate professor (1984) and full professor (1993).

In addition, from 1990 to 1994 Bellace was vice dean and director of the Wharton Undergraduate Division. During her tenure, she shepherded through significant changes to the undergraduate curriculum, broadening the number of courses offered and introducing a strong international component.

On the academic side, Bellace, who also received a Master of Science in Industrial Relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1975, has been general editor of the Comparative Labor Law Journal since 1985, and on the executive board, U.S. Branch, of the International Society for Labor Law and Social Security since 1986. Last year she was appointed to the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Standards of the International Labor Organization. She is well-known in the academic community for her research over the past decade in three main areas: the rights of fair dismissal, employment protection in the European community and the issue of comparable pay for work of equal value.

She is a strong proponent of the need for both undergraduate and graduate students to experience other cultures and learn new languages. As a faculty member, she has been a visiting academic in England at the University of Southampton, University of Warwick and London School of Economics, and in Belgium at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. Her two children, ages 8 and 10, have attended a French language camp in Minnesota for the past two summers, and her husband Geoffrey Latta, travels abroad frequently as head of international compensation services for a management consulting firm. Bellace herself has a working knowledge of French and Italian.

As for the choice between administrator or academic, Bellace appreciates what she calls the “creative tension” that the two roles can generate, but sees herself eventually going back into teaching and academic research.

The following pages offer brief glimpses of Bellace as both administrator and scholar.

The Administrator

When Bellace assumed the role of deputy dean on July 1, 1994, an administrative assistant handed her a list of job responsibilities, organized by month. It was less than two pages, double-spaced. It didn’t take Bellace long to realize that the brevity was misleading.

Many of the issues that the deputy dean is required to handle weren’t on the memo, including, for example, mediating faculty complaints, settling disputes over office space and offering career advice to junior faculty. More predictable are her responsibilities in the areas of curriculum change, personnel decisions, promotions and tenure offers, committee and department chair appointments, research centers, quinquennial review committees and lawsuits.

Although her job is often described as “chief academic officer,” Bellace compares herself also to a corporate chief operating officer. Much the way a COO is frequently responsible for high-level human resource issues, Bellace works closely with the faculty at Wharton to ensure that departments operate at optimum efficiency in delivering courses across the divisions and that research is facilitated through various forms of support. The personnel aspect of her job is especially crucial this year given that the vice deanships of three divisions — undergraduate, graduate and doctoral — turned over in July. “The deputy dean makes sure the transition is smooth and institutional knowledge isn’t lost,” says Bellace, who retains oversight authority for all three deanships.

Although the past year has brought a number of accolades for Wharton — including top rankings in business magazine polls and the School’s successful completion of its $200 million fundraising campaign — Bellace cites a number of initiatives that she would like to undertake over the next 12 months. They include:

HIRING. “At the moment, our departments are running very well, but three of them — finance, marketing and, to some extent, accounting — are very short of people. This comes at a time when demand from students in these subjects is greater than ever.

”Overall our class sizes are larger than we would like. We hope to grow the size of the faculty slightly over the next five years.”

RESEARCH. “Research is what makes us the number one business school. It’s extremely important to the faculty and it’s what attracts them to Wharton. I think we can offer faculty more support in writing, producing and distributing research.

“We’re also looking at how we can help the faculty become more international through, for example, an increased number of exchange programs, more faculty seminars abroad, and support for research in the area of global strategic management.”

UNDERGRADUATE CURRICULUM. “The undergraduate curriculum is due for a review next year once the first class to have gone through the full four years graduates. So far, it’s going well. The leadership component [Management 100, a required course for all incoming freshmen which focuses on teaching leadership, communication and teamwork] has received relatively good responses, but we still want to improve it.

“We also need to look closely at what students bring to Wharton from their own backgrounds — written communication skills vs. oral communication skills, for example — and then structure the program accordingly.

“The foreign language requirement should be analyzed as well. [As of three years ago, undergraduates must either be proficient in a foreign language when they come to Wharton, or must become proficient in one while they are here.] We don’t have complete data on how many students came in at the proficiency level, or how many semesters of a foreign language students took to meet the proficiency requirement. We need that data to determine whether the requirement serves a useful purpose in the curriculum.

“We also want to analyze how students are constructing their courseload to make use of the global environment category. [Students are required during their four years to choose three international courses out of a list of 80, including many from the School of Arts and Sciences.] It would be interesting to determine whether students make choices based on a particular region, or a time period, or are they simply taking three courses that are offered at convenient hours.”

MBA CURRICULUM. “Here we want to look at several areas, including strengthening Management 653 [where first-year students analyze a case that combines material from other core courses in order to get a cross-functional perspective on particular disciplines/strategies].

“Right now, the first-year load is very heavy, particularly in contrast to the second year. There may be room for some consolidation in the first-year core, or shifting to the second year.

“We also want to revisit the leadership course [a required class for all first-year MBA students designed to teach teamwork, communication and negotiation skills], which is on an upward trajectory but still needs fine-tuning.

“We should consider expanding the global immersion programs [half-credit minicourses offered to first-year MBA students which include a four-week overseas trip in May to study the target country’s economy, culture, history and politics]. At the same time, I don’t feel the program should be required, since many students are international and/or have already traveled abroad extensively. For them, it may not be a cost-effective way to spend their money or time.

“Classroom facilities are another priority. More and more students are coming in with laptops rather than PCs, which means we need more outlets, more modem bars, perhaps more assignments that can be downloaded, and so forth. Undergrads may be ready for this as well.”

Bellace is particularly interested in women’s educational and employment experiences as they relate to business careers. The number of women entering Wharton’s MBA program has remained relatively constant over the past few years, she says, for a number of reasons. First, there was a big increase in the 1970s and early 1980s, because demand, which had been pent-up for so long, was finally released. That demand has now leveled off. Second, more and more women are aware of how difficult it is for a woman, especially if she has children, to sustain careers.

And third, fields like law and medicine are more clearly certifiable than business. “If you go to law school you’re a lawyer; if you go to medical school, you’re a doctor. You have a license that shows this. Your competency is proven. That’s not true in business. It’s not always clear to many women how they will prove themselves,” Bellace says.

Also, there is a lack of knowledge as to what a career in business means. “TV doesn’t glorify this field the way it does some others, like medicine or law. So if you ask a 17-year-old to consider a career in accounting, often she’s not really sure what that means.

“We need to get to people earlier about how one prepares for certain jobs. I still find it surprising that at the high school level girls are not being asked by college counselors what they see themselves doing in five years. Young men understand more clearly that what they do in college has a direct connection to their entry into a career, whereas young women still tend to view college as a place where you explore academic fields that appeal to you but don’t always offer a direct connection to career entry. That’s not necessarily bad, as long as women realize that they will most likely need to get an advanced degree in order to enter certain fields.

“Basically, men are still urged to think more pragmatically than women.”

Bellace’s appointment as deputy dean in July 1994 followed four years as vice dean and director of Wharton’s undergraduate division.

“When Tom Gerrity became dean (in 1990), it had never occurred to me to do an administrative job. But after speaking to him about the undergraduate position, it seemed like a great challenge,” says Bellace, noting that part of the job’s appeal was the faculty decision in 1990 to implement a new and more internationalized undergraduate curriculum, a process that was completed two years ago.

“I feel that was probably where I made my greatest contribution,” says Bellace, whose accomplishments included the creation of exchange programs for students in Milan and Hong Kong, and semester abroad programs in Lyons and Madrid. “In the course of four years, I was able to conceive of, and get approval for, an International Studies Program, a unique, integrated dual degree program between Wharton and Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences.”

The Scholar

Bellace’s research areas include American labor and employment law, European equal employment law, multinational labor relations, and comparative labor law. In the last year alone, she has traveled to international law conferences in Italy, England, Switzerland, Japan and Belgium.

Below she offers comments on areas that she has either researched or lectured on both in the U.S. and abroad.

INTERNATIONAL LABOR MARKETS: For executives and entrepreneurs, the U.S. is the best country to work in. First, executive compensation as a multiple of the average industrial worker is much higher than in other countries. In addition, high salaries here don’t get criticized the way they do elsewhere, such as in Great Britain and increasingly in Germany, even though in the U.S., salaries and perks are more public because of SEC reporting requirements on executive compensation.

In Japan, the measurement is different. Perks are not included in salary figures, so a Japanese executive’s lifestyle is often ‘higher’ than his compensation figure might indicate.

Second, there is broad agreement that management acts in the interest of the company, but what that actually means is open to debate. In the U.S. it tends to be measured by shareholder value. In certain European countries, the notion is broader. Top management acting in the best interests of the company must consider not just shareholders but also employees and the geographic community in which the firm is located. The structure of company boards reflects this. In large German companies, one half of the seats on the top board are held by shareholders representatives and one half by employee representatives.

Also, the role of government in many European countries is much different than in the U.S. In Europe, government is seen as having a role maintaining a social market. It is intended to have some role in ameliorating the impact of capitalism on the labor market. That is not the case in the U.S. Here, for the most part, labor law is seen as creating some minimums, such as the minimum wage, minimum safety standards, and so forth, and then allowing certain avenues for procedural fairness, such as laws against discrimination. It doesn’t attempt to regulate the labor market to the extent you find in continental Europe.

One of the huge problems for the European Union at the moment is that the United Kingdom has an entirely different approach to labor law than other member states on the continent. In the effort to harmonize labor law, the British approach doesn’t mesh well.

For example, civil law countries — which include all the countries of western Europe except the U.K. and Ireland — tend to want comprehensive legislation. They prefer codes to regulate things, and they want rights and obligations clearly laid out. Common law countries, by contrast — such as the U.S. and U.K. — see the law coming in only when there is a dispute. Otherwise they say to the different parties, ‘You voluntarily set your own standards.’ Laws are relatively non-interventionist. So the idea that the law would in minute detail set closing hours for shops hasn’t occurred to us. But on the continent that is common. Until very recently, shops in Germany were ordered by law to close at 6 p.m. In Italy, private employment agencies are unlawful because the state is seen as the appropriate body for overseeing the labor market and preventing exploitative recruiting practices.

EUROPEAN WORKS COUNCIL: At an international colloquium in Belgium earlier this year, we discussed a new directive aimed at all companies operating in more than one country within the European Union. Starting in 1996, these companies will have to supply certain information to their European Works council in such areas as size of workforce. This is to give employees information on the company they work for. The feeling in Europe is that if shareholders know what the company is doing, so should the workers. Up until now, legislation of this type has been on a national basis: e.g., Germany has its own works council law, as does Belgium. The problem from an employee’s viewpoint is that if you work for a company that has subsidiaries in several countries, you may not get the full picture.

I’m surprised this hasn’t gotten more coverage in the U.S., because with all the U.S. companies that have subsidiaries in Europe, we will be the number three country affected, behind Germany and the U.K.

AGING OF THE WORKFORCE: One of my interests in the past decade has been the changing nature of work, the move from an industrial society to an information society. If we go back to an industrial society, we see that what is important is strength and speed, and the ability to conform to a stringent work discipline. A worker’s usefulness declined after it had reached a peak in his mid 30s to early 40s. Such a system impacted negatively on women because women weren’t as strong as men and because child bearing and child rearing kept them out of the labor force during some of the peak career time. Women were shunted to the margins of the labor force and were essentially a secondary labor market.

The whole way we viewed the labor market was that by age 45 you had topped out, and at age 55, you were sliding out and by age 65 you were certainly out, if not before.

But when you look at the type of work we do today, strength is irrelevant. Speed is not, but it’s mental speed vs. manual speed. The ability to work under close supervision is no longer necessary. In fact, just the opposite. People have to be able to work without close supervision. They have to be self-paced, self-monitoring and work well in teams.

All this changes the way we look at work. First of all, the male/female difference becomes irrelevant. Also, age becomes much less important. If somebody can think quickly and possesses great judgment, what difference does it make if he or she is 55 or 35? If someone is 52 and applies for a job, what should employers think? They should think that this person has 18 more years in the labor force, maybe more. But that is not the way we are accustomed to looking at someone who is 52.

The baby boom has had an enormous impact on this phenomenon. Most baby boomers won’t be able to afford early retirement at 57 because they will still be paying for their children’s education. Many see themselves working until they are 70.

One effect of this is that employers must look more closely at the issue of career progression, in the sense of making jobs more interesting for their employees. People who feel they have topped out and there is no place to advance tend to become less committed, less satisfied. Sometimes people talk about leaving their jobs almost as a form of escape. ‘I wish I could set up my own business.’ Not because they want to stop working but because they see decreasing fulfillment in their current employment. Starting a business might be the solution for some individuals, but it’s not the solution for a quarter of the labor force.

WOMEN IN THE WORKPLACE: In looking at the issue of equality for women, there is always the question of whether the glass is half empty or half full. If you compare 1965 to 1995, you find tremendous differences. The first, and the one that is frequently overlooked, is the ability to control fertility. Women coming out of college or high school are no longer assumed to be working for a temporary amount of time before they stop to have a baby. This is not the pattern, especially for college-educated women. Right now, 75 percent of women who have a college degree and babies under the age of one are in the labor force.

As to whether women still face prejudice from male managers, it’s relative. Go back to 1965 again. I don’t think a woman who was 22 with a college education could get a career track job. Now managers do realize that women are here to stay. They are just trying to figure out if this particular woman is the one who will stay. Studies have shown that most younger women assume they will not leave the workforce and will work for most of their lives. And in fact, a greater number of students entering college as freshmen are women, more than 50 percent now as compared to about 30 percent in 1965.

Consequently, another huge difference today is that companies now find it worthwhile to invest in human capital needs, i.e., to provide more workplace training and more opportunities for women to advance. Back when Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, a woman might have graduated summa cum laude from Vassar, but companies generally were not willing to spend resources on improving her skills. At age 37, a woman of that generation was ‘less’ than she had been at age 22.

A third difference is the nature of work. That’s where you see the wage gap closing because of the greater premium on education. Women can compete on educational grounds and they do it quite well. The data shows that the wage gap is closing. Why? In the 1960s, it was said that women were underpaid. It could have been that men were overpaid, particularly in certain jobs that didn’t require much education or high skill level. Now that is no longer true. Instead, pay increases in many of the overwhelmingly male, blue-collar jobs have not kept up with inflation. In relative terms, these jobs have fallen behind, which has led in part to the angry high-school educated male phenomenon.

AMERICAN LABOR LAW: One of the problems in American labor law at the moment is that a great deal of it comes from the New Deal. As I mentioned earlier, we are at a different economic stage now, which means many of the basic notions in our law are obsolete.

For example, much of our labor law makes an incredibly sharp distinction between workers and supervisors/managers. Workers are the ones who don’t think and who do as they are told. Once you think and have discretion, then you are not covered anymore by the National Labor Relations Act. That’s a meaningless distinction. We expect our workers to think and make decisions. The Fair Labor Standards Act with its distinction between exempt and non-exempt workers is an artifact that made sense in the 1930s but doesn’t now.

The statute that really surprises me is the American With Disabilities Act. It sailed through Congress because our political leaders realized there was widespread support for it, even though it can impose significant burdens on employers. We might talk about anti-discrimination laws being unpopular, but then when you ask which ones should be repealed, there isn’t widespread support for repealing any specific statute.

I agree that laws can be burdensome, but as I said in an article, law is society’s response to the market … In democratic countries, law is the non-violent way citizens express their will. The challenge for a lawyer doing research in a business school is to balance this democratic imperative with the need of a free market to operate efficiently.