Look at your iPhone and imagine your apps are gone. Facebook, Uber, the Weather Channel, the Huffington Post, Scrabble, Google Maps, Kindle, Instagram, LinkedIn, White Noise, Bitmoji…. Apps you use all the time with barely a thought. If Steve Jobs had his way, they wouldn’t have existed.

This is according to Walter Isaacson, author of the biography Steve Jobs, speaking at the recent launch of the Anne and John McNulty Leadership Program at Wharton. He said that Jobs had a powerful need to maintain end-to-end control, and when the iPhone came out, he wouldn’t allow any third-party apps. He viewed them as “polluting his product.”

The Apple management team kept standing up to him, according to Isaacson, saying “‘You’ve got to let people build apps on top of this.’ And finally he responded, ‘OK, you a-holes, if you think you’re so smart, so go ahead and do it.’”

A statement like this was essentially Jobs’ version of “collaboration,” said Isaacson. “It was his way of saying, ‘You might be right, let’s try it.’”

“Within a year it was a two-billion-dollar industry,” he added.

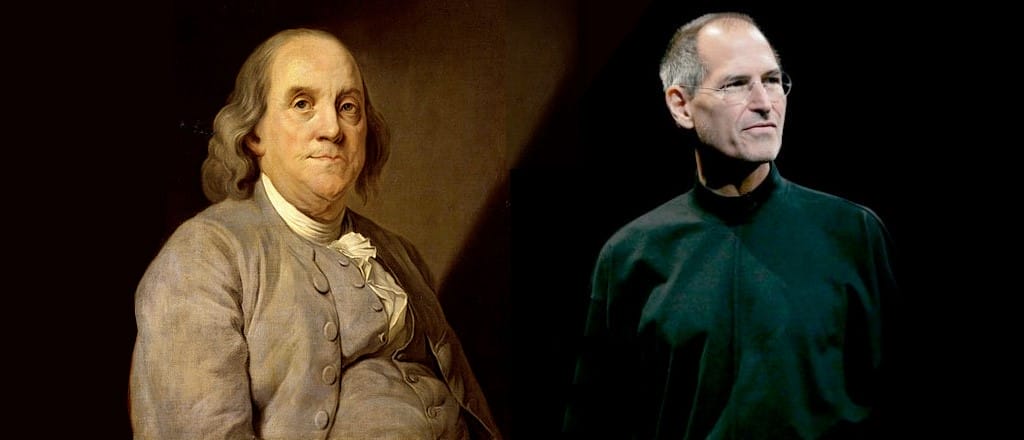

Isaacson, a former TIME editor and former CEO of CNN, is a well-known biographer of great American leaders. In addition toSteve Jobs (2011), he has written Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003), Einstein: His Life and Universe (2007),Kissinger: A Biography (1992), and The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution (2014). He is now President and CEO of the Aspen Institute, a nonpartisan educational and policy studies institute based in Washington, D.C.

At the McNulty Leadership launch, Isaacson wove a tale of two famous figures who at first glance appear to have little in common: Steve Jobs and Benjamin Franklin. What leadership lessons can be drawn from their lives?

Ben Franklin: Bringing People to the Table

Any American business leader who practices collaborative leadership owes a great debt to Ben Franklin, according to Isaacson. “Franklin really helped invent … leadership based on collaboration and teamwork.”

Isaacson talked about the different personalities that came together to write the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, who can essentially be seen as Franklin’s leadership team. “You needed somebody of high rectitude in George Washington that everybody would respect. You needed really smart people like Jefferson and Madison. You needed passionate people like John Adams and his cousin Samuel. But what you really needed in Philadelphia for both of those conventions was somebody who could make everybody collaborate and bring them together.”

Referring to the “horrible hot summer” of 1787 in Philadelphia, in Independence Hall when the idea of a U.S. Constitution seemed to be “going down in flames,” Isaacson recounted how Franklin, then aged 81, delivered what Isaacson considers one of the great leadership speeches of history.

“He said, ‘When we were young tradesmen here in Philadelphia and we had a joint of wood that didn’t hold together, what we would do is we’d shave a little from one side, and then take a little from the other, until you had a joint that would hold together for centuries. So, too, we here at this convention must each join together and each part with some of our demands.’”

Franklin’s notion, said Isaacson, was that “compromisers don’t make great heroes, but they do make great democracies.” One of the major compromises that Franklin helped engineer resolved the heated battle for control between the large and small states. The solution gave the U.S. its bicameral legislative body: The House of Representatives in which representation is determined by states’ population, and the Senate where every state gets two senators regardless of population.

Isaacson noted that with the many institutions Franklin started in Philadelphia, whether it was a school, a hospital, or a library, he inscribed over the door, “‘The good we can do together exceeds what we can do individually.’”

“It was that spirit of collaboration — even more than the rectitude of Washington in that chair — that I think helped set the tone for the innovative leadership that I’ve seen throughout all the things I’ve written about in leadership in the United States and elsewhere.”

Steve Jobs: A Collaborative Leader?

Steve Jobs has often been described in extreme terms, both negative and positive: a control freak, a jerk, cruel, brash, narcissistic, brilliant, a dynamo, a genius, one of the greatest business executives of our time. The word “collaborative,” though, doesn’t often turn up.

“Steve was somebody who was not known as a collaborative leader,” noted Isaacson. “If you read about him, you’ll see that he was strong and tough, and often unkind.”

But like Ben Franklin, Steve Jobs had the ability to marshal and inspire a great team, said Isaacson. And he valued the team above all. “When he was dying … in 2011 and I was there, I asked him at one point, as a leader of a business that he had started with a few friends … in a garage, and created what was then the most valuable company on earth: What product, what innovation [are you] proudest of?”

Isaacson expected Jobs to say the Mac, the iPhone, or the iPad. But he answered, “‘Here’s what I’ve been trying to tell you. Making products is hard. But what’s really hard is making a great team that will continue to make great products.’” Jobs said the best thing he ever did as an innovator and leader was to create a great team.

“Somehow or another, he engendered loyalty,” said Isaacson. “He would tell people that something they did wasn’t very good, he would be really tough on them, but he had an inspiring vision. And he was able to put together a very tight-knit team that would walk through walls with him.”

Isaacson shared an anecdote about the team working to build the original Macintosh computer. Jobs, while admiring the beautiful design of the new machine, noticed that the circuit board was “ugly” and the chips weren’t lined up right. The engineers responded, “‘Well, Steve, it’s in a sealed case. Nobody’s going to see it, nobody’s ever going to know.’”

Jobs made the group of about 25 engineers go to the backyard of the house he had grown up in, about 12 miles from Cupertino, California to see a fence he had helped his father build when he was about eight years old. Jobs said his father had insisted they make the back of the fence as attractive as the front. When Steve questioned this, saying nobody would ever see it or know, his father responded, “Yes, but you will know.”

Apple delayed shipping the Mac for about eight weeks, said Isaacson, while the engineers made the circuit board inside it “beautiful.” Jobs then got all their signatures on a whiteboard so he could have them engraved inside the machine.

He reportedly told them, “‘Now you’ve got the passion of a real team that are true artists.’”

‘Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish’… But How Long?

The story of Steve Jobs’ leadership also deeply involves the question of maintaining the energy and focus of a startup while scaling a business. Scaling typically involves collaboration and compromise, something that according to Isaacson, was a major challenge for Jobs for many years.

Isaacson described how Jobs treasured a framed back cover of the Whole Earth Catalog with the saying, “Stay hungry, stay foolish.” For Isaacson, this was an expression of his startup mentality: “Get out of that groove when you’re too comfortable.” In a similar vein, he believed in products before profits. “What Steve said was if you focus on profits mainly, you’ll start cutting corners. You’ll save a little here and there…. But if you make a really great product, the profits will follow.”

For Isaacson, one example of putting products before profits was the iMac desktop computer that Apple launched in 1998. (Some may remember that computer as Isaacson does, “looking like something George Jetson would’ve used: the translucent blue case.”) It was designed by Jony Ive, today Apple’s much-lauded Chief Design Officer.

Isaacson points out that it was a desktop computer, not meant to be carried around, yet it had a prominent handle on top. Why the handle? Apple engineers complained that it would add significantly to the cost.

“[Jobs] said, ‘No, if you have that handle, it makes the computer look friendly. People are scared of computers. It’s just a sign that, I’m at your service, you can touch me. That way my mom won’t be afraid to grab the computer… if [people] just see that beautiful recessed handle.’” It was a hit, noted Isaacson. According to his book about Jobs, it sold 800,000 units in its first year, making it the fastest-selling computer in Apple history. Notably, 32% of the sales came from people buying a computer for the first time.

Of course, not compromising ultimately got Jobs into trouble. “He gets ousted by keeping that mindset,” said Isaacson. “[John Sculley, Apple’s CEO at the time] and the board oust him in 1985 because he has too much of a startup mentality. He’s not doing the tradeoff between ‘all right, we need these dollars for marketing, let’s take it away from manufacturing.’ He wants his own manufacturing plant and he wants end-to-end control of the product.”

But 10 years later he is brought back. “This is a Shakespearean drama,” said Isaacson. “Apple needed him because they had done the opposite: they had become a big old IBM-like, flabby company.” Jobs returned as CEO to lead Apple in the creation of landmark products such as the iPod, iPhone, and iPad.

“In the end he learns to make the type of leadership collaboration and sometimes compromises that turn Apple from [having] a startup mentality to a sustainable mentality,” said Isaacson.

As far as leadership takeaways — from either Ben Franklin’s or Steve Jobs’ life — Isaacson resists the notion of making bulleted lists such as “The Leadership Lessons of…” (while confessing that he has sometimes been obliged to do so). “I think the best way to learn how to be a good leader … is studying other people. Everybody does it differently.”

Isaacson delivered what he called “a shameless plug for biography…. Reading good biography, and living and learning from other people, instead of saying, ‘Give me your five lessons.’ Because you then have to look inside yourself.”

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared as a piece on Knowledge@Wharton. View the original post here.