Britain’s Brexit and Brazil’s Bolsonaro. Italy’s Salvini, and our Trump. The Yellow Vests in France. Populism is the trend in democratic politics today. But how should we understand it? How should we respond to it?

I am increasingly convinced of three things:

First, the populist outrage expressed toward all elite institutions (governments, corporations, universities) is not a top-down case of charismatic leaders inflaming a rudderless society. Rather, today’s populist leaders are the product of profound societal dissatisfaction with an elite-driven political economy.

Second, the rise of populism is at its core an economic phenomenon—with enormous social and political consequences—driven above all by the deteriorating economic situation of the middle class.

Third, there is negativity toward “the system,” including democracy itself. The deep potential support base for populist leaders who want to blow it up—not reform it through the established push and pull of democratic politics—is highest among millennials. We used to think of young adults as being the most idealistic and committed to democracy. No longer.

Put it all together and we are living in societies that are much more pessimistic—some resigned, many angry—than at any time I can remember. Today’s strong economic growth, low unemployment, and high stock prices do not provide the support for the status quo that they have before. That’s because they no longer translate into material or psychological well-being throughout society, breeding rampant pessimism.

Here is the evidence supporting my contention about the links between populism and pessimism.

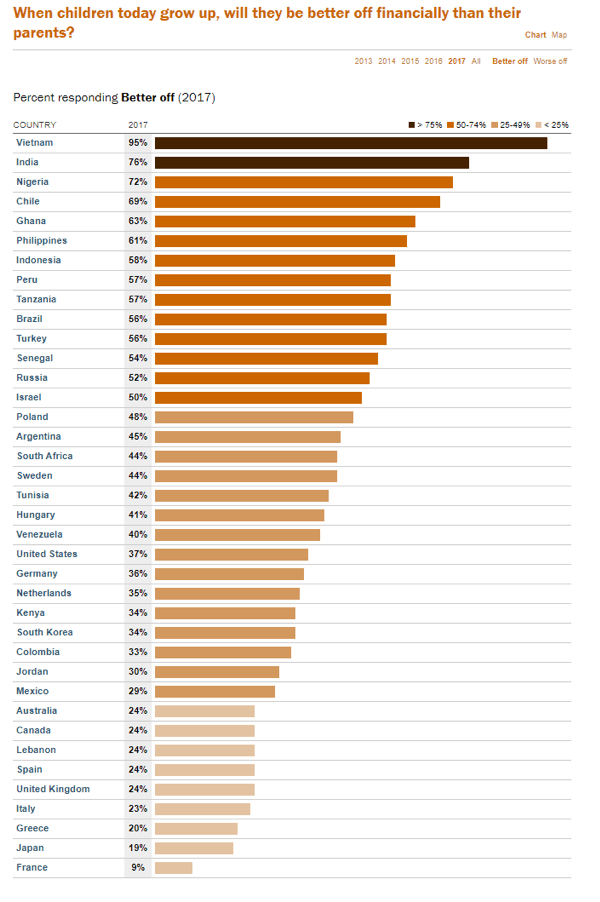

Fact 1: People don’t believe the future will be better for their children.

I suspect that there has been one fundamental indicator of optimism in the Western world since at least the Industrial Revolution: parents believing that their children’s lives will be better than their own. Today, according to the Pew Research Center, this optimism only persists in emerging markets. The high-water mark for optimism in the West is Sweden, the utopia of social democrats, where 44 percent of citizens believe that when today’s children grow up they will be better off financially than their parents. At the bottom of the pessimism barrel are the countries with long-term and likely irreversible economic malaise—France, Japan, Greece, and Italy. America has long been the paragon of inveterate optimism. But today, only 37 percent of Americans believe their kids will be better off, slightly less than in Venezuela.

(Photo: Pew Research Center)

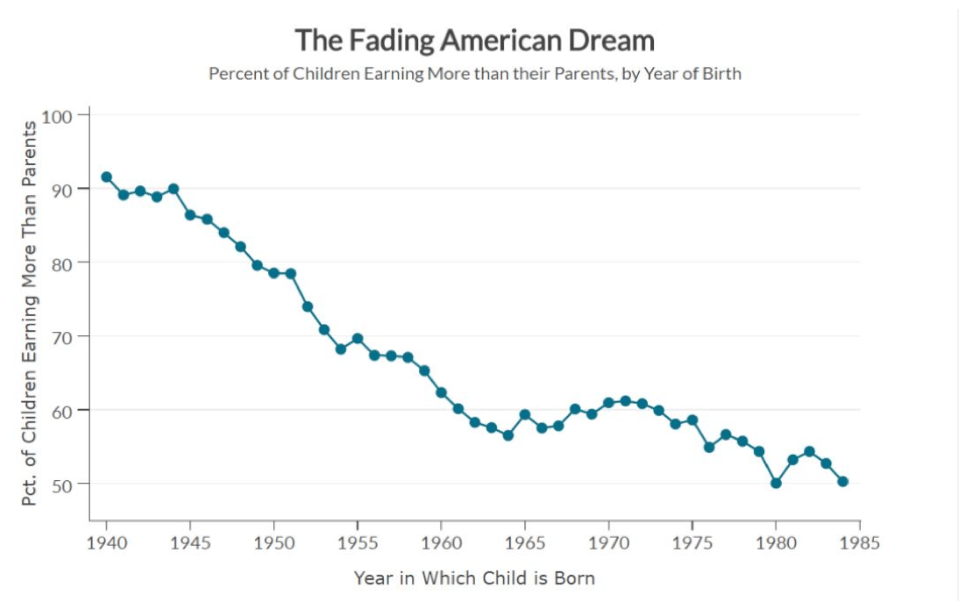

Fact 2: The root cause of pessimism is deteriorating economic life chances.

Take a look at the graph below about America from the Equality of Opportunity Project, now known as Opportunity Insights and led by Harvard economist Raj Chetty. Instead of asking people how they feel about the future economic prospects of their children, the graph plots what actually has happened to Americans based on when they were born. The data are striking.

Ninety percent of children born in America in 1940 went on to earn incomes that exceeded those of their parents—justifying that generation’s faith in the American dream. For millennial Americans born in the 1980-85 window, it is a coin toss whether their incomes will exceed those of their parents. No wonder they are anxious about their futures and disillusioned with the institutions—government, big business, and higher education—promising to make their lives better.

(Photo: Opportunity Insights)

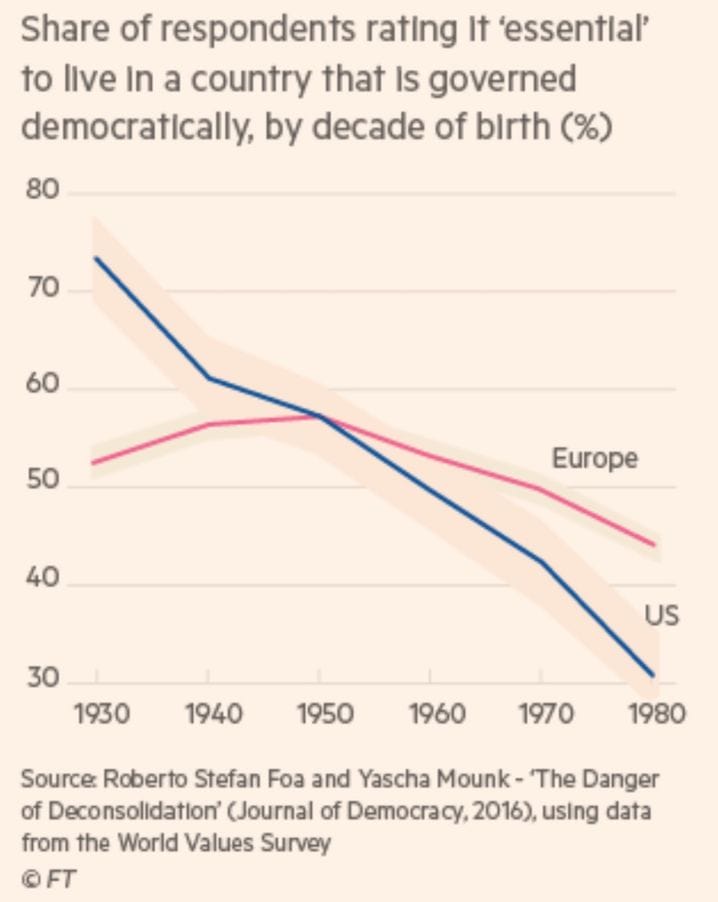

Fact 3: Younger people are less committed to democracy.

The graph below is as astonishing as it is disturbing, but it is the consequence of deteriorating opportunities for younger people in most, if not all, Western countries.

It’s no surprise that there was a vast difference between people born in the 1930s in America and Europe regarding their attitudes to democracy. But after World War II, the two paths converged around support for democracy among baby boomers born in 1950. A solid majority believed that it was “essential” to their overall quality of life that they lived in a democracy.

For the first millennials born in 1980, the percentage believing democracy was essential to their lives has dropped to under 45% in Europe and to a staggeringly low 30 percent for Americans—all according to the World Values Survey.

These data should not be over-interpreted. They do not mean that most people would prefer to live in autocracies. But the data do show that younger people have become at minimum complacent and at maximum disenchanted when it comes to the value proposition of democracy.

(Photo: Financial Times)

What should we do now? The obvious answer is more inclusive economic growth. But that will require real political leadership that seems so absent today. And this is not a fleeting thing. Rather, the left–right party divisions that became entrenched in the 20th century are ill-suited to generate the leadership the West so desperately needs.

What we need are leaders who do not channel outmoded partisan divides. Populists avoid and often defy partisan labels. But they represent a back-to-the-future view of the world that I believe is ultimately futile and self-defeating. Instead we need forward-looking “progressive” leaders who highlight actionable ways to spread the profound benefits of technology and globalization more broadly than they have been in recent decades.

Progressive might sound like “left” to many, but I don’t intend it that way. At their core, progressives are optimists—people who believe the future will be better than the past and are committed to working to get there. By contrast, conservatives cling to the past because the future is just too risky. On my definition, Ronald Reagan was progressive. Remember this opening line from one of his 1984 campaign ads—“It’s morning again in America”? But British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is conservative—if only Britain never entered Europe in the first place. So, too, is Donald Trump, with Make America Great Again.

What we need is a new generation of 21st century progressives who can lead us to a future in which increasing prosperity is shared throughout society, not who try to reverse the irreversible tide on globalization and technology. I don’t know who they will be, but I would certainly filter them based on their embrace of a better future and whether their optimism is anchored in reality.

The jury is still out on Emanuel Macron in France. Who knows how long Pete Buttigeig’s time in the sun will last in America. But their approach—eschewing partisan labels, being relentlessly positive, and focusing on actionable solutions—seems directionally correct to me. Certainly more promising than Boris Johnson’s Trump 2.0 plan for Britain.

Crisis is a wildly overused term. But I join the many who believe today’s capitalist democracy is in crisis. The way ahead is to go forward, not to look back. Left–right partisan politics can no longer be looked to for solutions. Our political paradigm must transform before our economic challenges can be met and society can heal.

Editors note: Geoffrey Garrett is Dean, Reliance Professor of Management and Private Enterprise, and Professor of Management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This post was originally published on LinkedIn, where he was named an “influencer” for his insights in the business world. View the original post here. Follow Geoff on Twitter.