Innovation and entrepreneurship for the improvement of society have been hallmarks of generations of Wharton graduates. More recently, “social entrepreneurship” and “social impact” have emerged as additional, important aspects of the Wharton entrepreneurial approach.

The remarkable work of Dennis Rezendes WG59, who died June 16 at the age of 85, is a good example. When he graduated, the Fels Institute of Government was still an integral part of Wharton’s graduate school. His Wharton MGA (that is, master’s of government administration) prepared him to become not only a competent manager and leader, but also a skillful social entrepreneur. He used these skills to create a medical service that today is of immeasurable help to all of us: hospice care for the final stage of life.

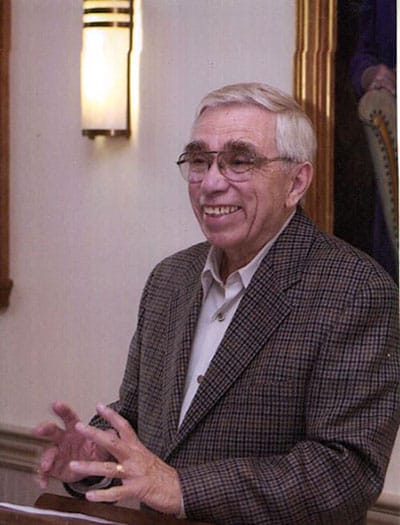

Dennis Rezendes (1930-2015)

Rezendes’ career began in 1960 as director of administration for the then-famous Mayor Dick Lee of the city of New Haven, Connecticut. During the 1960s, New Haven was a hotbed of urban innovation that led to the emergence of national programs such as Model Cities, Community Action Agencies and Early Start, among others.

Successful in his work in New Haven, Rezendes was soon invited to become president of the Greater Hartford Process, which was a joint effort by insurance companies, business and community leaders of Hartford, along with Maryland’s famous developer James W. Rouse. The objective was the creation of a modern, planned, racially integrated community in the Hartford metropolitan area. It was a time of great hope and energetic creativity, and the perfect setting for Rezendes.

Another significant social innovation of more personal impact that was emerging at that time resulted from the work of Elizabeth Kubler Ross in the United States and of Dame Cicely Saunders in England and dealt with society’s response to the needs for end-of-life care. Based on Ross’ and Saunders’ philosophy, the dean of Yale’s School of Nursing, Florence Wald, initiated an Americanized version that in 1971 led to Hospice Inc., a New Haven-area hospice home-care program.

Known for his administrative and political skills, plus a personal philosophy that resonated with this innovative approach, Rezendes was recruited in 1975 by this first-ever American hospice institution to serve as its chief executive. He thus became the leading entrepreneur for the creation of a new hospice program of care for the terminally ill in the U.S. Like any good social entrepreneur, he strived to create a team that would not only build the best possible hospice center in Branford, Connecticut, but also shape a new hospice care model with important innovations. These included hospice services that provided both inpatient and home care, redirecting attention to the patient’s family as the prime unit of care and providing patient care through an interdisciplinary team.

As any good Wharton entrepreneur would, Rezendes met with potential investors, banks, donors, foundations, local, state and federal government agencies, state legislatures, Congress, and a network of health care professionals and systems across the United States—anyone he could interest in his expanded cause. These activities had one goal, which was the adoption of hospice as a universal health service in the U.S., available to all who needed it.

Hear it expressed best in his words from his memoir, Looking Back to the Future:

“My own belief was that for hospice care to make a difference, it would need to become an accepted and respected part of the health care delivery system. … We need to weave hospice care into the very fabric of the health care system and, in the process, humanize health care for everyone.”

Hospice palliative care began to spread across the U.S. In October 1975, Rezendes organized the First National Hospice Symposium in Branford, which pulled together hospice care professionals from across the United States. After a number of these annual events, the National Hospice Organization was founded in 1978, with Rezendes serving as the new organization’s first executive secretary. Its immediate goals were to provide much-needed national leadership and to define and develop the critical standards for hospice care. Now known as the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, the organization’s other primary goal was to seek legislation that would include the right to palliative health care for everyone in the U.S. who sought it. In 1982, he orchestrated lobbying efforts that resulted in a remarkable achievement for National Hospice: hospice care became a benefit under Medicare Part B.

In his 2014 book, Being Mortal, Atul Gawanda, professor at the Harvard Medical School, concluded:

“We’ve been wrong about what our job is in medicine. We think our job is to ensure health and survival. But really it is larger than that. It is to enable well-being. And well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive. Those reasons matter not just at the end of life, or when debility comes, but all along the way.”

Having reached the same conclusion in 1975, Rezendes devoted his professional talents and experience to the well-being of the most vulnerable: those facing death from old age or terminal illness. The outcome, establishing hospice care as an integral and essential element of medical services for everyone in the U.S., represented for him the fulfillment of his passionate personal vision and a dedicated career achievement.

Rezendes was an idealist who did what he did not for personal profit but for the “common good,” the fundamental value of a public administrator. He serves as a notable example of Wharton’s long-term devotion to social entrepreneurship and a model of success for generations of Wharton graduates to follow.