The First Battle of Marne, which occurred 100 years ago this month, has been called “the battle that changed the world.” The German advance into France at the outset of World War I was halted just short of Paris, and four years of bloody trench warfare followed. American involvement came much later, most decisively in the 1918 Second Battle of the Marne, a turning point leading to the end of the war within three months.

The loss of life in that span was staggering. Nearly 50,000 American soldiers were killed in barely six months of action in 1918, including almost a thousand from the Philadelphia area. U.S. military casualties were double the monthly rate later sustained in the longer World War II. France and Britain lost close to four times as many soldiers during World War I as fell during World War II.

I was struck when visiting London this year by four large stone memorial panels in Waterloo Station, alphabetically listing nearly 600 railway employees who died “in The Great War.” Almost inconspicuously smaller, barely the size of a handful of those names, was a nearby little metal plate, dedicated simply to 626 men who “gave their lives in the 1939-45 war.”

Though it ended more dramatically and conclusively, the second global conflict was to a considerable extent an outgrowth of the first, and the earlier war thus amounted in many ways to the ultimately more significant break with the past.

The war that shocked the world with industrial scale slaughter from 1914 to 1918 had far-reaching and long-lasting effects across modern industrializing societies and on the businesses operating in those countries. (Impacts on the University of Pennsylvania began well before America declared war on Germany in 1917.) Insular empires of Eastern Europe imploded, overseas colonial empires of Western Europe went into irreversible decline and technological advances accelerated. Corporate structures were shaken up, while trade barriers, economic instability and uncertainty mounted and intensified.

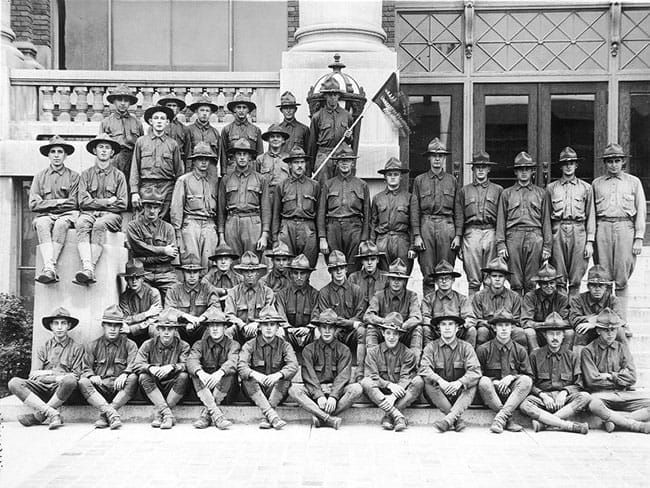

A Student Army Training Corps demobilizing in the Quadrangle, Dec. 1919. Photo credit: University Archives Digital Image Collection.

The prewar common market within Austria-Hungary fragmented after 1918 into local economies made up of many smaller, often quarrelling states. Imperial Germany, the Continent’s economic powerhouse before 1914, became the inflation-wracked Weimar Republic. Czarist Russia was replaced by the autarkic Soviet state and its policy of self-sufficiency. Even victorious Britain suffered war-related losses to its gross domestic product comparable to the heavy cost of the war effort itself. The gold standard, championed by Britain and enabling mostly free international flows of trade, capital and labor before 1914, never recovered after 1918. International business instead had to cope with trade barriers, “beggar-thy-neighbor” devaluations and bank failures (such as that of Austria’s Creditanstalt in 1931).

New opportunities also opened up, however, with the war’s acceleration of technological development. Petroleum power, electrification and rapid improvements in communications and transportation underpinned new growth industries. The disruption of the war and its protectionist aftermath encouraged the pursuit of new markets; the revamping of production methods and management techniques (for instance, New York’s General Electric and Pennsylvania’s Westinghouse diversified into consumer products after the war, created new “merchandising” divisions, and formed the new joint venture Radio Corporation of America); and new forms of cooperation and consolidation (such as the holding company in America and the Interessengemeinschaft in Germany).

In many countries, the war also transformed relations between corporations and governments. In the United States, President Woodrow Wilson’s “dollar a year” men used their business expertise to help with wartime economic mobilization. Industry and agriculture were heavily regulated, and the railroads and merchant marine nationalized. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon adopted the pragmatic view that “government is just a business,” while President Calvin Coolidge went a step further and proclaimed that the “business of America [itself] is business.”

Closer involvement of executives with politicians had downsides. There were conflicts of interest (for example, in the Teapot Dome scandal that broke open in 1924), and public attitudes toward corporations soured after the 1929 crash and the Great Depression.

The growth of conglomerate business organizations and extensive government bureaucracies, nonetheless, persisted for decades. Though seriously disrupted by the cataclysm of World War II and the fissure created by the Iron Curtain thereafter, businesses and government regulators in Europe—in all their different institutional forms—have also grown in size, power and complexity, and in the extent of their interaction.

Among the belligerents of the Great War, and across the globe, a legacy of the First World War was that it helped foster much of what is still considered modern business structures and practices. Ironically, the transformations catalyzed by an unwanted war almost universally regarded as a disaster have helped underpin a subsequent century of successfully developing private enterprise.