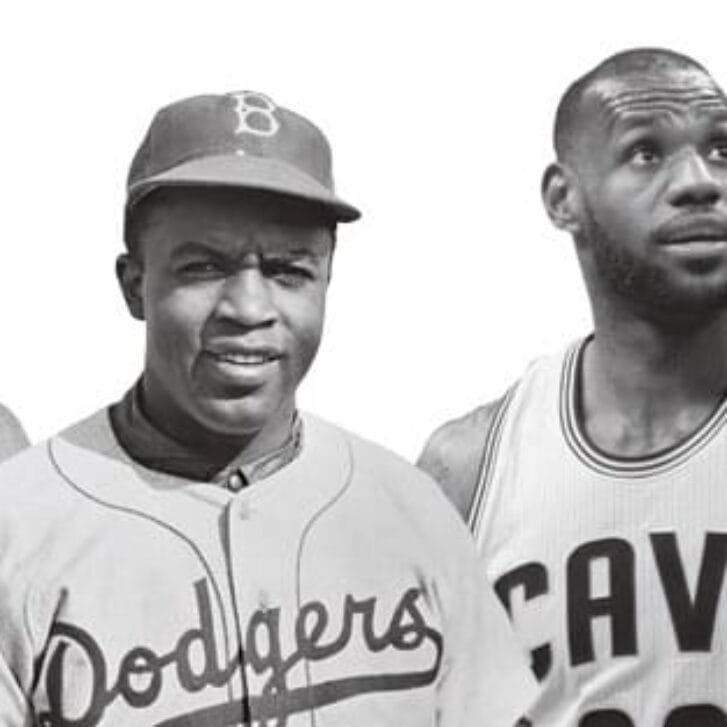

1996 and 1997 mark two little noted 50th anniversaries: The first is the “reintegration” of the National Football League in 1946; the second is Jackie Robinson’s integration of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Major League Baseball in 1947.

Generally, anniversaries are cause for celebration. But while much has changed on the field in these two sports, there has been little change in the owner’s box. African-Americans occupy a hefty percentage of the positions on the field, but no African-American holds a controlling interest in a major league professional sports franchise. Professional sports franchise ownership will constitute the true measure of African-American success in the sports industry.

Like baseball, organized professional football was originally an integrated enterprise as early as 1904. Much like the rest of society, there was a brief pre-Jim Crow period of broad integration. Unlike baseball, however, the impact of Jim Crow did not end the African-American presence. Blacks played in organized professional football leagues until 1933, the year that an unofficial ban on blacks went into effect. Although no formal announcement was made, black athletes were simply not invited back to training camps and none were signed out of college. The last blacks to play in that season were Ray Kemp and Joe Lilliard.

Like baseball, organized professional football was originally an integrated enterprise as early as 1904. Much like the rest of society, there was a brief pre-Jim Crow period of broad integration. Unlike baseball, however, the impact of Jim Crow did not end the African-American presence. Blacks played in organized professional football leagues until 1933, the year that an unofficial ban on blacks went into effect. Although no formal announcement was made, black athletes were simply not invited back to training camps and none were signed out of college. The last blacks to play in that season were Ray Kemp and Joe Lilliard.

Most point to the move of the Boston Redskins football franchise to Washington, D.C. — below the Mason-Dixon line — as the reason. The Redskins became the first NFL franchise to be based in a southern city. Franchise owner George Preston Marshall apparently felt that southern fans wanted to cheer for an all-white team. Under Marshall’s influence, blacks disappeared from the League.

Re-integration of the NFL occurred 13 years later in 1946, largely as the result of pressure from the black press of the day. The Cleveland Rams had just moved west to Los Angeles and wished to play their home games in the publicly-owned Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The black press, particularly the Los Angeles Sentinel, pointed out the potential illegality of the use of a public facility by a segregated team. The issue received widespread newspaper coverage.

Other fortuitous circumstances worked in favor of the Rams. Los Angeles franchises were uniquely suited for integration because of the local collegiate success of Rams players Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. Both were stars at UCLA and had proven marquee value. Washington was Jackie Robinson’s backfield mate at UCLA, Strode an end for the school’s team. This reintegration preceded Robinson’s much more widely celebrated debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The national focus, however, was on baseball. Baseball was the sacred national pastime, not football.

According to one 1995 study of nearly 300 individuals with any ownership interest in professional sports, fewer than ten were African-Americans and none owned or combined to own a controlling interest. The only substantial African-American ownership in a major professional sports league, outside of the Negro Leagues, was a brief period in 1989-1992 when businessmen Peter Bynoe and Bertram Lee owned a 37.5 percent share in the Denver Nuggets. During this period they acted as the managing partners (before eventually selling the Nuggets to majority partner COMSAT).

Why is this absence of African-American ownership so striking? One reason is that the people who play in games are predominantly black, almost 90 percent in the National Basketball Association and 65 percent in the National Football League. Major League Baseball has a significantly lower percentage of African-Americans at approximately 18 percent. There are few areas in American society where such a racial underrepresentation in ownership exists. Major entertainment entities, such as Black Entertainment Television, are owned by African-Americans, as are large publishing entities such as Johnson Publishing. Even the multinational Beatrice International is owned by the family of the late African-American businessman Reginald Lewis. But not major league sports enterprises. Yet professional sports could certainly benefit from diversity at the ownership level in at least three ways.

First, there is clearly a value to society in having people of color in positions of power and serving as role models. Second, diversity can have a positive impact on previously homogenous groups, as evidenced by the change in the predominantly white male U.S. Senate after sexual harassment testimony during the Clarence Thomas hearings. In the business of sports, addressing the particular concerns of players and fans of color are issues which a more diverse ownership group could handle better than the current one. Finally, great wealth seems to accrue to owners who sell their teams. This wealth, in some form, could benefit minority communities.

Today, the price of sports franchises, upwards of $200 million, brings into question whether this is an appropriate time to enter the market, particularly for individuals. Financial returns are not likely to come until the franchise is sold, and the operational costs, particularly salaries, are immense. Corporate ownership of teams is certainly the emerging trend and African-Americans generally do not control the large corporations capable of making such forays into the sports franchise market.

Some are concerned that franchises are now overvalued. But where these transactions do make sense the current owners can mandate that people of color must be a part of any ownership group. They can also seek out people of color with the resources to purchase a team and give them the opportunity to review the investment.

There is not much celebrating this year for football—although there should be for the efforts of the individuals who made integration on the field happen. Washington, Strode and others struggled in much the same way that Jackie Robinson did. The true celebration should occur when there is African-American ownership in this highly visible industry.

Kenneth L. Shropshire is an associate professor of legal studies and real estate and author of In Black and White: Race and Sports in America, New York University Press, 1996.