How competitive is Anthony Noto? Well, here’s a good indication: He played football in his junior and senior seasons at West Point with torn ligaments in both knees. But Noto didn’t just play. He excelled, earning Academic All-American and All-East honors as the team’s star linebacker. And at the same time that he was battering opponents on the field, he was dominating his classmates off of it. By the time he graduated from West Point in 1990, Noto was the highest-ranked mechanical engineering major in his class.

“I honestly think I’m the kind of person that is driven by fear of failure rather than striving for success,” says Noto, WG’99. “I tend to go to bed scared and wake up terrified.”

Noto’s drive served him well at West Point. It hasn’t hurt him since graduation, either. After starting his career as a brand manager with Kraft Foods in Chicago, Noto landed on Wall Street–and, during his time at Goldman Sachs, established himself as one of the brightest young analysts in his sector.

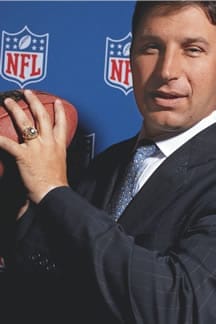

Institutional Investor magazine named him the No. 1 analyst for Internet stocks each year between 2003 and 2007, and he was widely viewed as one of the most respected analysts in the communication, media and entertainment sector as well. But despite the success, and despite making partner at Goldman, Noto grew hungry for a new challenge. He found one, too. Just as he was preparing to leave Goldman, Noto got a call from someone at the National Football League, wondering if he might be interested in serving as the league’s chief financial officer. He took over the position two years ago.

In many ways, it’s a dream job for Noto–a way to bring together both his childhood and professional passions–but it’s not without its challenges. As CFO, Noto is charged with helping the league to navigate the economic downturn and playing a key role in collective bargaining negotiations with the NFL Players Association. Those negotiations, which have just now begun, are expected to be long and difficult.

Noto sat down with Wharton Magazine for an interview in late August.

Why football?

My family was very athletic. We played every sport we could. But I think football was unique because it is the ultimate team sport. I think the team aspect of it and the passion required to play a game that requires hitting on every play attracts a unique personality to excel. And I think I had that personality.

But I almost gave it up. I have two brothers. My parents both worked and all of us playing sports challenged them from a logistical standpoint. So my parents made the tough choice of telling us that we could each only play two sports. I ended up choosing basketball and baseball. And I remember my Pop Warner coach calling and saying, “Anthony, are you really not playing football anymore?” I lived in a basketball town. Everyone played basketball first. But my older brother was a freshman at the time, and he was playing high school football. It was summer and because my mom didn’t want me sitting around home alone, she would drop me off with my older brother and I’d be there watching practice all day. So one day the Varsity coach came up to me and asked, “Why aren’t you playing football?” I explained why I chose to play basketball instead. He said, “But you’re already here anyway. Why don’t you just play for us?” I told him I was only in eighth grade, but he said that didn’t matter. By the end of the summer I was the starting quarterback for the freshman team, as an eighth grader.

So when did you realize that you had a special talent? And why did you choose Army?

I guess around my 10th grade year, I started to realize that it’s not normal for a player at a skill position like quarterback to play up a year or two. I also continued to play hockey and baseball. By the time I started looking at colleges, I was really planning on playing both football and baseball in college.

I chose West Point for reasons beyond academics. It was about getting more than an academic degree. It was also an education in leadership. I went to West Point to build the skills that I would use for the rest of my life. For me it wasn’t about being in the military. Serving in the military was the price I was willing to pay for the lessons I’d learn along the way.

After graduation you worked as an assistant coach at Army, then went down to Fort Benning and the Army Ranger School. At what point did you move into the private sector, and how did you end up at Wharton?

I started out professionally with Kraft Foods in Chicago, in brand management. I spent roughly two years there, and was then asked to transfer to work on new business development in White Plains, NY. But I had been going to business school at night at the University of Chicago, so I asked Kraft to support me in getting my MBA on the east coast. I was fortunate to get accepted to Wharton. As we left for the holiday break during my first year at Wharton, we got our first finance and securities analysis books. I had never taken a finance class. I started to read them over the holidays and could not put them down. When the new semester started and I got back to Wharton, I said, “I have to switch to finance.”

You ended up at Lehman Brothers as a research analyst, and eventually went on to Goldman Sachs, where you became the highest rated analyst in your field. What do you think it is about your personality that made you a good fit in the field?

I think being an equity research analyst requires an understanding of strategy, finance and financial analysis. It also requires creativity and an understanding of marketing. Those are really many of the same skills that attracted me to the brand manager job at Kraft. The biggest differences between that job and being an analyst was the degree to which you used each skill set and the additional but critical step, as you would guess, of how to pick stocks. As an analyst, you’re basically doing the same thing as a brand manager, but instead of doing it for one company, you’re doing it for 30 companies. As a brand manager you have almost all the information. As an analyst, you’re doing the research to get the information. Solving that puzzle was very intriguing to me. Another aspect that I enjoyed about Wall Street was that it’s incredibly competitive. That bell rings for a reason every day. It’s a battle. And when you go out there and say a stock is going to go up, but it doesn’t, that’s painful. You’re losing. That drives me.

You won more than you lost, though. So why did you leave?

The thing about being a research analyst is, it’s like running a marathon at a sprinter’s pace. It’s like having to predict or being ready to predict the weather every second. You’re constantly on the hook for having an opinion. It was a great job for me and I loved it for the 10 years I did it. But I knew we had accomplished what was possible. We were ranked No. 1 in our field. We rose from the abyss and near-death experience of the Internet bubble to rebuild a great team and a great franchise. I was looking for a new challenge.

The NFL had not had a full-time CFO in the five years prior to your arrival. So how was the job presented to you?

I knew we hadn’t had a CFO for a number of years, and that the new commissioner [Roger Goodell] was looking to consolidate the reporting of all of the different individuals that were handling the various responsibilities of finance and strategy under the office of the CFO. I think he also knew that the business dynamics of the league were changing such that having a CFO integrated into labor, business operations and strategy would be a necessary part of the executive team to help drive decisions. To me, the job of the CFO is to use financial and non-financial information, in order to appropriately allocate resources or capital, to gain access to resources and to manage risks. The job gave me a chance to leverage all of my professional experiences in a sport that I love.

Can you tell me your first impression of the NFL, from a business point of view, upon your arrival?

I realized that our financial outlook and status 100 percent starts and ends with the quality of the game.

One hundred percent. Without a strong game that fans want to go interact with, we have no base. But if we have a strong game, we can leverage that content to find more and more ways to engage and interact with fans. We can create revenue streams from the fan engagement. In a sense I like to think that the league makes money to invest in increasing the appeal of the game as opposed to playing the game to make money.

How would you succinctly describe the league’s financial health today?

I would say the economic environment has clearly challenged our revenues in 2008 and again in 2009. I think our [executive] team has aggressively attacked those challenges in the interest of continuing to have a strong economic foundation as we move forward. Even without the economic challenges our biggest challenge is that player costs are fixed at a very high level, and when revenues are challenged, it exacerbates that problem. So our biggest challenge going forward is getting a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA).

The CBA negotiations are widely predicted to be difficult.

The meetings with the new labor leadership have already begun. And I think we are very focused on ensuring that we get an agreement that is good for the players, good for the owners, and good for the fans. I believe the timing of that agreement is less important than getting an agreement that is a good one for all of the parties involved.

At the end of the day, what is the league’s most important revenue source?

Two of the biggest revenue streams are attendance and media rights, and I actually would not separate the two. And moving into this year, I would say when it comes to gate-related revenues, we would expect to be challenged in the current environment. Consumers have been negatively impacted by this recession. Our corporate partners have been impacted, too. We’ve met these challenges head on. But it would be wrong to say we haven’t been impacted at all. Still, I think our team has done a great job. We’ve been able to achieve our financial profit goals, despite the challenges. But I want to emphasize, we are challenged, especially because of the fixed player costs.

Why has the NFL been so successful over the years?

Again, I think the owners, their families, their predecessors, the Commissioners and others have recognized through the years that everything begins and ends with a great game. I mean, think about the competitive balance in the league, the integrity of the game, the focus on player safety. If you think about the very structure of the leagueÑfrom the revenue sharing agreement to the governance and ownership rules to stadium developmentÑall of those things have combined to make sure that the game is a great one, first and foremost.

What about international growth? The NBA, for instance, has poured a lot of resources into China.

International is an important area of growth for the NFL. We want to engage with fans and take the game outside of this country, and games and media are the way to do that. We’re playing one game a year in London, and that’s been very successful. We’d like to maybe do more in that areaÑmaybe play two or three games a year in London or possibly more broadly in Europe. The Buffalo Bills, meanwhile, have extended beyond their borders to play games in Toronto. If we can successfully play more games, for instance, in London, there could one day be a franchise there, sure. That’s not inconceivable. I wouldn’t say it’s probable at this point. But it’s possible.

We have seen how technology has negatively impacted the music business. Is the NFL doing anything to protect itself from potentially threatening technology?

We are very cognizant of the role that technology plays in the delivery of our product to our fans, and we’re aware that we need to exploit technology rather than be exploited by it. The most important thing for us, if fans want to consume our product in a certain way, is that we have to come up with a value proposition for that rather than ignoring it completely and having them figure it out on their own. We want to be the creator of the vehicle, not the recipient of the vehicle.

Finally, I’m wondering about your impressions of the job now that you’ve been here two years. Is it what you expected?

People ask me that question quite a lot. And I would say that, looking back, I have not second guessed my decision to come at all. Making the transition just before the start of the economic and credit upheaval, while terminating the league’s labor agreement and starting negotiations, has presented the type of challenges that drive me. Even without these unique moments in time I consider myself incredibly fortunate to be part of such a great game and great institution.