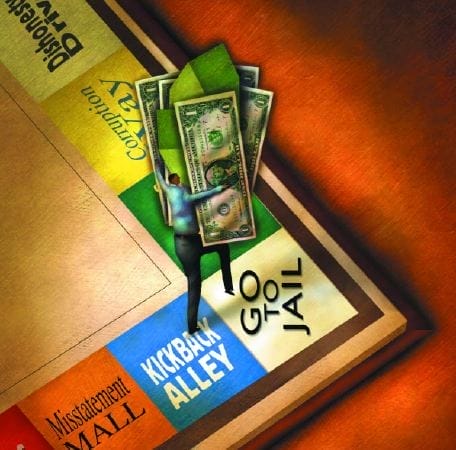

We won’t bother with the list. Let’s just say it starts with Enron, and at this point no one is sure where the litany of ethically challenged companies will end.

One thing is sure, however. The public has spoken – through congressmen and the president, through jurors, shareholders, and the media. The message? Ethics do matter in the corporate world; and if businesspeople fail to abide by certain standards, they will be sent – at least in America – straight to jail.

A new law President Bush signed this summer creates an independent body to oversee the accounting industry and introduces new criminal penalties for corporate fraud, both moves seemingly designed to quell unease on Wall Street that failed to abate when the president proposed less sweeping changes.

“Clearly the administration’s view of this has changed pretty rapidly,” Gary Gensler, W’78, WG’79, told The New York Times recently.

Gensler, once a senior Treasury Department official with the Clinton Administration and now co-author of the forthcoming book The Great Mutual Fund Trap, has made news more recently for his hand in helping craft the new business guidelines.

“I think it’s strong legislation, and it’s very needed,” he says. “Something was seriously broken.”

Gensler is hardly alone among Wharton alumni, faculty, and students grappling anew with ethical questions. Stephen Cooper, W ’70, has just taken on the almost unfathomable job of steering Enron through bankruptcy. MBA students are refocusing on how to recognize and avoid conflicts of interest. And Legal Studies faculty members are busily scouring the new federal law so they can teach students about its implications.

The Wharton community faces these challenges even as a recent CBS News poll suggests not even one-third of Americans believe most corporate executives are honest. About 79 percent of respondents said they believe questionable accounting practices are widespread, while more than two-thirds said they believe CEOs are commonly compensated illegally.

Such issues are taking a front seat for people on campus as well as for those whose monthly paychecks come straight from the kinds of companies under the spotlight.

“Students now don’t need to be told why this is relevant,” says Professor Thomas Dunfee, who teaches international business ethics at Wharton and regularly brings corporate leaders into the classroom to speak. One recent guest was the former head of auditing at PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

Dunfee co-authored Ties that Bind: A Social Contracts Approach to Business Ethics with fellow Wharton Professor Thomas Donaldson. Together, they suggest corporate leaders have the same unspoken contract with shareholders and the public that early political thinkers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau proselytized between government and its subjects.

Dunfee has long believed in introducing students to accomplished executives and professionals who can stress the importance of ethical behavior. But current events have given professors an even stronger hold on student interest.

Dunfee pins many of today’s troubles on a lack of independence found among corporate board members and those working for major auditing houses. Some professors serving on corporate boards, for example, receive large donations to fund their academic research.

“Those things can corrupt your judgment in subtle ways so that you don’t realize you are making biased decisions,” Dunfee says.

For anyone on hiatus for the last year, here’s a taste of the recent ethical lapses either known or suspected within corporations:

- The Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission have investigated accounting irregularities at Enron.

- Last December, the company became the nation’s largest corporate bankruptcy when it stunned the investing world by disclosing hundreds of millions in debt that the energy concern had kept (seemingly legally) off the books. Making matters worse, when it came time for Congress to take action, it was hard to find a politician in Washington who hadn’t taken a campaign contribution from the company.

- WorldCom usurped Enron as America’s biggest financial failure by filing for bankruptcy protection in July. A top officer previously acknowledged to insiders that WorldCom was violating accounting standards but might fail if it reported its financial condition honestly. That revelation came in an Associated Press story following up on WorldCom’s disclosure that it had a multi-billion-dollar hole in its books.

- President Bush faced renewed scrutiny for having sold more than 200,000 shares of stock in Harken Energy Corp. when he was a director there in 1990. The sale came two months before the Texas oil company reported an unexpected loss. Although the SEC cleared Bush of insider trading years ago, the stock sale didn’t look good when revisited by the post-Enron news media.

- And then there is Martha Stewart, whose image tarnished in the wake of revelations that she sold 4,000 shares in ImClone just before the stock price plummeted in December. Stewart is a personal friend of Sam Waksal, ImClone’s former CEO accused of securities fraud and insider trading for allegedly tipping off relatives to ImClone’s imminent demise.

Lawrence Zicklin, WG’59, former managing partner of the investment house Neuberger Berman LLC and the founder of Wharton’s Carol and Lawrence Zicklin Center for Business Ethics Research, said he realized long ago that American businesses were rife with conflicts of interest. But he never imagined such a wholesale ethical slide.

“Not in my wildest imagination,” he says.

Inside an Investment House

Zicklin made his professional mark at an investment house founded during the Depression. Back then, Roy Neuberger managed money for the wealthy. But by 1950, the firm opened itself to a whole new class of clients: it became one of the first to offer a no-load mutual fund to individual investors.

Zicklin made his professional mark at an investment house founded during the Depression. Back then, Roy Neuberger managed money for the wealthy. But by 1950, the firm opened itself to a whole new class of clients: it became one of the first to offer a no-load mutual fund to individual investors.

Neuberger Berman, Inc., went public in 1999 with a reputation for integrity as well as performance, something Zicklin attributes to the fact that the top managers kept their eyes continually on the future value of the firm. They always sought to protect “the franchise,” as Zicklin calls it.

The company’s above-reproach reputation was so important, in fact, that Zicklin once fired a man for taking advantage of a competitor. It didn’t matter that the employee had pressed the advantage on behalf of a Neuberger Berman client.

“I fired him because I understood that he didn’t really understand what our business was about,” Zicklin says.

It was that kind of dedication to doing what’s right that led Zicklin from the boardroom to the classroom. What started as a weekend seminar on business ethics for faculty at New York University has become a second career in teaching since he retired as Neuberger Berman’s managing partner.

Today, the firm manages $61.9 billion in assets, and Zicklin is passing on its ethical etiquette through the Zicklin Center at Wharton.

What Went Wrong? The View from an Auditor’s Office

With nearly two decades of experience in public accounting, Dana Michael, W’82, has personally witnessed the damage bad conduct can wreak.

With nearly two decades of experience in public accounting, Dana Michael, W’82, has personally witnessed the damage bad conduct can wreak.

From his post investigating mergers and acquisitions for Ernst & Young clients, Michael has seen some of the worst in corporate misbehavior. About five years ago, he was looking into a company as a possible acquisition for a client when the target company fired its chief financial officer for embezzling roughly $500,000.

The man set up a bogus consulting company, wrote checks to the business, and mailed them to a P.O. box he rented. Astoundingly, the CFO had pulled the same stunt at his previous employer, but escaped jail time by returning some company stock options. In return, the employer agreed not to press charges or tell anyone what had happened. When a new company called for a reference, the old firm simply didn’t return the telephone message.

“It’s amazing,” Michael said, marveling that a simple followup could have saved the CFO’s second employer hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The situation highlights a common problem in companies: failure to segregate duties. In Michael’s experience, as long as financial responsibilities such as collecting receivables, recording them, and writing checks are divided among different employees, the risk of ethical or legal violations remains slim. At WorldCom, for example, the trouble was that the CFO was allowed to make entries straight into the company’s financial records without anyone questioning their authenticity.

Michael believes the problem should have been picked up by even a junior accountant ages ago. Collusion among employees is much more difficult to detect, but an individual’s misdeeds are usually discovered readily, at least in Michael’s experience.

Still, Michael doesn’t believe today’s more vigilant climate will prevent future abuses.

“There are a lot of creative people out there on Wall Street and in companies,” he says. “They may slow down over the next couple of years, but they are not going to go away.”

Gensler, however, remains confident that the new legislation he helped usher through Congress will dissuade some would-be wrongdoers, if only because it promises prison for errant executives.

“There’s nothing that quite focuses the mind like that,” he says.

Zicklin echoes Gensler’s hope. People are more honest, he says, when someone is watching them.

An International Perspective

That old adage about honesty may be even more true in the international arena, where companies making inroads to newly opened markets often face a climate of outright corruption.

Thomas Caleel, an MBA student who worked in direct investing in Moscow from 1995 through 1998, recalls a climate in which otherwise upstanding western executives were caught up in some fairly sleazy dealings.

“There was a tremendous amount of bribery and insider dealing and just awful things,” Caleel says.

Philip M. Nichols, an associate professor in the Legal Studies Department at Wharton, is working with the Zicklin Center on a research project about the attitude toward corruption in transitional countries.

“Corruption is often justified by both bribe-givers and bribe-takers as a culturally accepted – even expected – practice,” Nichols says. “The possibility … has both practical and theoretical implications: practically, it would weaken the arguments for criminalizing transnational bribery; theoretically, it would weaken the proposition that proscription of bribery is universal.”

Unfortunately, corruption is so pervasive and accepted in some places that certain American companies barely bother hiding the fact that they grease a few palms. But Dunfee says it’s wrong to blame only those who take the bribes. Corruption could not continue if the supply dried up, he says. Caleel agrees.

Unfortunately, corruption is so pervasive and accepted in some places that certain American companies barely bother hiding the fact that they grease a few palms. But Dunfee says it’s wrong to blame only those who take the bribes. Corruption could not continue if the supply dried up, he says. Caleel agrees.

Still, Transparency International, a Berlin-based coalition against corruption, puts America smack in the middle of the list of countries it says are home to companies that sometimes pay for the privilege of doing business in certain areas.

Each region of the world has its own specific problems, of course, but others are shared across geopolitical boundaries. In Pakistan, for example, questions of child labor surround the manufacture of top-quality soccer balls. Businesses with divisions in South Africa used to opt for segregated facilities to appease the apartheid government. And increasingly, foundations that say they seek to help the impoverished in the Middle East are being asked about their ties to suspected terrorist organizations.

But as surely as apartheid posed a challenge to human rights, it also provided a blue print for how corporations can bring pressure to bear against such repugnant values. A collection of companies laboring under apartheid gave birth to the Sullivan Statement, a set of governing principles under which participants promised to stand with one another and against South Africa’s racist government.

Dunfee points out that corporations could do the same in countries where dishonesty is rife, if only they would publicize their encounters with corruption.

Bribery, for example, can survive only if it is allowed to sneak through a back door. Force the corrupt to enter through the front, and they won’t be so likely to proceed, Dunfee contends.

“I think it would help move the country forward,” Caleel adds. “But realistically, it’s tough because a CEO has the responsibility to keep generating returns.”

For Students, Ethical Dilemmas Outside the Classroom as well as Within

Wharton junior Samantha Rudolph remembers vividly Friday, Oct. 26 of last year – the day a fellow student leapt to his death from the eighth floor of his campus dormitory.

Around campus, people hurried to soothe one another. The University organized grief counseling sessions. The Graduate Student Center set up crisis intervention training. Friends planned a memorial.

Rudolph spent the weekend weighing her responsibilities. As a news director of Penn’s student-run television station, she knew the story had to be told. But she also was concerned about the student’s family.

“We didn’t know if the parents knew at that point,” Rudolph recalls. “We have a commitment to journalism, but we wanted to make sure we had the family’s privacy in mind, too.”

In the end, the station’s Board of Directors opted not to pre-empt regular weekend programming. They chose instead to include a short piece about the student’s death in the regular Monday broadcast.

The suicide posed one in an ongoing series of ethical questions Rudolph and her peers face at the station. Usually the conflicts have to do with free speech, such as whether to pull the plug on an anchor who slanders another student during a live broadcast. (The station is working on guidelines now.)

Rudolph says the station tends to lean on the conservative side of the ethical spectrum, a habit in line with Gensler’s advice to all students.

“When faced with the temptation to shade the truth or to shade reported results, lean against that wind,” he says. “Usually the one who can lean against the wind will be fine. You are not going to lose your job.”

As for Rudolph, she’s looking forward to the less regimented schedule of higher-level classes and perhaps more class time devoted to the ethical questions posed by current events.

So far her academic training in ethics has included a negotiating class in which some fellow students made up details to a case study. Lying wasn’t permitted, but some students took the rule to mean that if they could imagine something that didn’t directly conflict with the materials, then they could use it.

So far her academic training in ethics has included a negotiating class in which some fellow students made up details to a case study. Lying wasn’t permitted, but some students took the rule to mean that if they could imagine something that didn’t directly conflict with the materials, then they could use it.

“It did open my eyes,” Rudolph recalls. “It was my first exposure to the fact that people wouldn’t necessarily treat me the way that I would treat them.”

Caleel, who co-chairs the student Ethics Committee at Wharton, attributes such difficulties partly to Wharton’s rich diversity. Because the school welcomes so many students from so many different countries, he says, there are bound to be divergent ideas about what constitutes ethical behavior. With that in mind, the Ethics Committee organized a 90- minute presentation to be included in this fall’s MBA orientation.

“Wharton has done a fantastic job of creating an environment where you have to rely on your teammates,” Caleel says. “There is a lot of trust that you give, and I think that ethical conduct is a foundation here.”

He notes, however, that a university can’t alter someone’s moral fiber. It can only give the tools to evaluate one’s behavior and its consequences. Michael, the Ernst & Young auditor, agrees.

“I think ethics is really something that you learn when you are five years old,” he says.

A Gentle Reminder

The question of the moment seems to be “Where do we go from here?”

Dunfee admits there is an art as well as science to choosing ethical conduct. The first step is recognizing a particular situation as an ethical dilemma. Then, both Dunfee and Zicklin recommend applying a couple of tried-and-true tests:

1) Ask yourself, “Is this the start of a slippery slope to ruin?”

The principle behind this question holds that once a person crosses the line ethically – even in the most seemingly innocuous situation – it becomes easier to slide on the bigger issues. If it seems okay to take a box of pens from the office to use at home, it won’t be much of a leap to charge a box to your corporate American Express card. And once someone starts charging personal expenses to his company, he might be tempted to keep it up. Witness the Chicago woman who embezzled more than $240,000 from Andersen Consulting by filing fraudulent expenses. Her defense? She was a “shopaholic.”

2) Apply “The New York Times” rule.

How would you feel if what you’re doing today were printed on the front page of The New York Times tomorrow? If the idea gives pause, Zicklin suggests rethinking the choice.

Dunfee says that posing these questions will help people recognize where a particular decision falls on the spectrum between right and wrong. However, he also believes it’s too late to leave the business world to police itself.

Indeed, Gensler believes some of the most important aspects of the business governance legislation approved this summer are the parts that ensure someone is watching the watchers. He’s referring to the portions of the new law that provide for independent oversight of auditors and make them clearly responsible to shareholders via the board of directors, rather than to company managers.

For people doing business outside the U.S. as well as within, Dunfee and Donaldson suggest in Ties that Bind that a set of manifest global moral standards exist (they call them “hypernorms”) which may serve as ultimate guideposts for ethical dimensions of business decision making.

Although Dunfee is for government oversight, he also reminds us that being in the right legally doesn’t always mean one is in the right ethically.

“I believe that you get more influence out of norms and professional standards than you do out of specific regulations,” he says. “The law is not perfect.”

“I’m always worried the government can muck up something,” adds Michael, the Ernst & Young auditor. In addition to Dunfee and Zicklin’s suggestions, Michael says the number one improvement companies could make to protect their assets is to instill in lower-level employees the belief that it is OK to question what happens above them.

“I think that’s something important – that people aren’t totally cowed by the structure of the organization.”

New Federal Business Regulations at a Glance

Executives who destroy or alter documents sought in federal investigations could face up to 20 years in prison.

CEOs and CFOs who certify false company financials face 10 to 20 years in prison and fines of $1 million to $5 million.

A new private-sector, five- member board – made up of two accountants and three professionals from other fields – will have subpoena and disciplinary powers over the accounting industry. The Security and Exchange Commission, in consultation with the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve Board, selects board members.

Top officials and company directors are barred from accepting personal loans from their companies.

Accounting firms may no longer provide consulting or many other non-audit related services to companies that the firms audit.

Accountants who prepare financial reports for companies will be responsible to the board of directors rather than to managers.

Individuals who break the law may be banned for life by the SEC from serving as officers or directors of any public company. The SEC previously had to go to court to implement a permanent ban against a person.

Q & A with Dean Patrick Harker

Q: Do business schools have an obligation to address issues of ethics and morality in the classroom?

A: When Joseph Wharton approached the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania 1881 with a proposal to establish the first business school, his goal was to produce graduates who would “serve the community skillfully as well as faithfully in offices of trust . . . maintaining sound financial morality.”

This is the crux of the matter. In business, we hold positions of trust. In a publicly held company, we’re overseeing other peoples’ capital investments. When we manufacture a product or deliver a service, we’re warranting its quality and value in the economic exchange. Fundamentally, business is about relationships – relationships of trust that have far-reaching and deeply personal impact.

This is the crux of the matter. In business, we hold positions of trust. In a publicly held company, we’re overseeing other peoples’ capital investments. When we manufacture a product or deliver a service, we’re warranting its quality and value in the economic exchange. Fundamentally, business is about relationships – relationships of trust that have far-reaching and deeply personal impact.

Joseph Wharton made the point that as business professionals we not only hold positions of trust, but also that we must “serve the community” in doing so. In his view, the goal of business was to make peoples’ lives better, to advance society through economic development. And he rightly believed this required us all to act with “strict fidelity” to moral principles of equity and fair play.

So, yes, business schools have an obligation to address issues of ethics and morality, and I think we can be proud of the Wharton School’s historic commitment to that responsibility and the quality of our ongoing efforts in this important area.

But it’s also important to note that the graduates of business schools have a further obligation, and that is to act ethically and morally in the marketplace once they leave business school. Even with the best of instruction and experience, each person must still make the personal choices that fall on one side or the other of the ethical scale.

Some critics have argued that the spate of corporate corruption is a sign that business schools have failed in their responsibility of preparing their students in the area of ethics. If that were truly the case, we’d be seeing far worse and still more pervasive problems. That is not to say that the current situation is not serious, or that business schools can’t do more. But I do think it is an encouraging sign of the constructive role business schools have played, and will continue to play, in turning out responsible business professionals.

Sharon L. Crenson is a national writer for the Associated Press.