Born in Connecticut, brought up and schooled in Staten Island, Philadelphia and Manhattan, I entered the Wharton School in 1948, little knowing where it would lead. My father, a dedicated physician, hoped that the School would guide me into a less demanding career than his own.

I became interested in using Spanish for my Wharton School language requirement when I met Ray Cora W52, a wealthy classmate telling tales of his island home, Cuba—a paradise just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. I commenced Spanish studies in 1949 and credit my professor, Rafael Suarez, with furthering my desire to research Cuba.

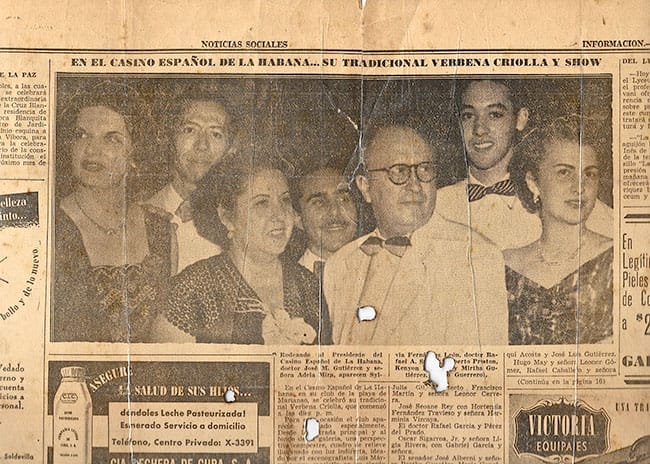

Carlos Prío Socarrás was president of Cuba in 1950 when Professor Suarez selected me and three other Penn students to matriculate for two summer sessions at the University of Havana. Another young male student studying hard at the university’s law school that year was Fidel Castro. The Cuban students would gather in the hallways, debating and smoking cigars; but I and my fellow Americans were warned to stay away from these “firebrands”; they were socialists, intellectuals with an inflammatory political message.

Meanwhile, my friends and I were enjoying the many delights available to us in beautiful Havana. We were honored guests at the luxurious beach clubs and restaurants; we met beautiful girls and were able to chat with them and dance at the nightclubs … only, as we soon found to our distress, in the company of the girls’ ever-present chaperones. But at night, once the ladylike daughters of the elite had been taken home by their watchdogs, there was nary a chaperone in sight!

There was also unbelievable poverty and filth. The division between the lush living of Cuba’s upper classes and the poverty of the starving homeless begging in downtown alleyways was obvious even to a privileged American boy without a thought beyond his next cigar.

In senior year, while my classmates were spending spring break in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, I decided to return to Cuba alone. It was 1952, and in a coup d’état but two weeks old, the America-backed dictator Fulgéncio Batista had just taken over as president. Conditions struck me as little different from those I had observed just two years prior.

Penelope and Ken Cardoza

In 1953, I married Penelope Roese, a year to the day after we met in New York City. During this time, while serving my country as an Air Force cadet, I came to the realization that upon graduation, I would be asked to shoot down and kill young Korean men of my own age—innocent young men who had done me no harm. My moral and ethical conscience made it imperative that I ask permission to resign the program. I spent the rest of my mandatory two-year service doing accounting work in Texas, doubtless using the bookkeeping skills taught me by the Wharton School. Upon my honorable discharge from the Air Force, I was helped by the G. I. Bill of Rights as I applied to New York University, where I spent six years, having decided I could best use my desire to help rather than harm mankind by earning a degree in the healing arts—specifically Dentistry, in which I showed great ability.

In 1959, television reported on the amazing feats of Fidel Castro, who had overturned the corrupt government of the all-powerful Batista. With only a small band of soldiers from out of the mountains to help him, Castro had succeeded in apparently giving Cuba back to the long-suffering Cuban people. My wife and I traveled to celebrate that Christmas/New Year of 1959 and 60, entering Havana just as most Americans were hastily leaving. The Cuban people were as welcoming as always, the music as wonderful. Food was in short supply and monotonously limited to chicken, fish, beans and rice. But everyone was fed, and there were no beggars along the Malecón. Spirits were high and the whole world applauded as the fancy hotels long held by the mob were turned from gambling casinos and drug dens into hospitals and schools and homes for orphaned children.

Ken during one of his return trips to Cuba

In the years since, I have shared the adventure of traveling to Cuba with my ever-growing family many times, staying at both private B&Bs and the nostalgic Hotel Naçional. My observations—of the advanced medical care, progressive mandatory schooling (accounting for Cuba’s 99.9 percent literacy), lack of homelessness, safety for women, zero tolerance of criminal behavior including illicit drugs—have led me to believe that the positive outweighs the negative, in spite of the efforts of a certain sector to convince the public otherwise. By sharing my informed opinion with people, especially college students, through classroom talks, I seek to advise those interested of the true facts behind the Cuban embargo.

Now in my 80s, I am retired from the dental practice I established in Honolulu in 1961. Still partial to tropical islands, my wife of almost 62 years and I share our Oahu home with our daughter, granddaughter and her husband, and two great grandchildren.

I keep in touch with my alma mater through school reunions, the Penn Club, and the fine publications presented by both the University of Pennsylvania and the Wharton School. I eagerly awaited the Spring 2015 edition of Wharton Magazine; surely, it would contain comments on the relaxation of the economic embargo imposed by the United States upon Cuba for the last 54 years, but not a word could I find concerning the historic new policies between Washington and Havana. [On Dec. 17, 2014, Cuba and the U.S. moved to restore diplomatic ties.]

Hence this letter: Because especially at this crucial time of transition, we need to encourage both media and universities toward the promotion of better understanding between Cuba and the United States, and who better to further this effort than Wharton? The very words, economic embargo alone should serve to alert and excite the Wharton scholars toward this goal.

—Kenyon Cardoza W52

Editor’s note: For the record, Wharton’s online research and news journal, Knowledge@Wharton, has been exploring the business implications of relaxed U.S.-Cuba relations—through the Cuba Opportunity Summit and the Wharton Digital Press book, The Road to Cuba.

This article was published as part of Wharton Magazine’s “Wharton Effect,” a series with tales of the School’s profound impact on the lives of alumni.