Success, in today’s complex and globalizing world of business, is usually linked to identifying and capitalizing upon opportunities. This implies orienting toward the future and leaving the past behind. Nowadays, focusing on building “track records” of excellence and adding value almost seems to be at risk of becoming “history,” meaning outdated. Instead, entrepreneurship and innovation have become the preferred paths toward “making history,” meaning—in some fashion—escaping from it.

Despite these trends, acquiring and applying knowledge of business history remains useful to future business enterprises. For starters, learning about business in the past is still pertinent to the training of future business leaders.

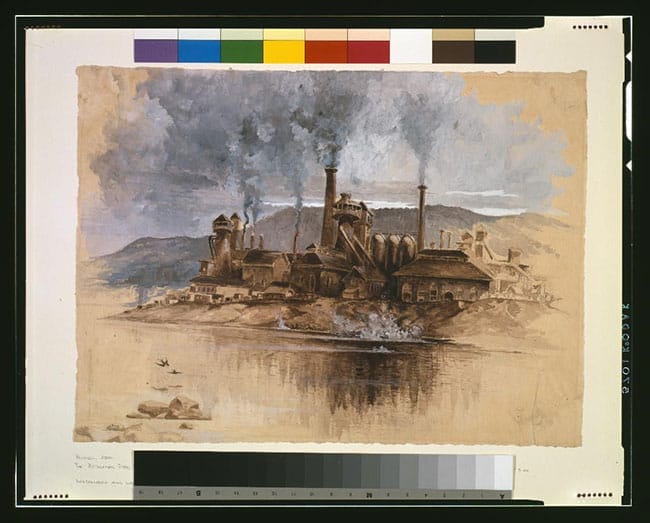

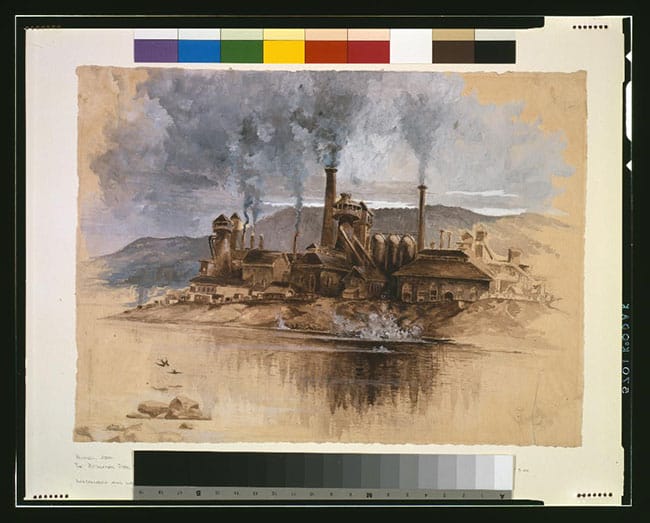

Bethlehem Steel Works in 1881, by Joseph Pennell. In 1904, Charles M. Schwab and Joseph Wharton created the Bethlehem Steel Corp. out of the Bethlehem Steel Co. Photo credit: U.S. Library of Congress.

In the traditional “case method,” business school participants grapple with concrete examples of past business challenges, thereby honing their skills at sizing up and responding to future decision-making situations. At Harvard Business School, the case method was adapted nearly a century ago from an analogous pedagogy pioneered earlier at the Harvard Law School, under the maxim:

“It is better to go up to the sources than to follow the rivulets downhill.”

[Christopher Langdell’s English translation of an earlier Latin maxim, as quoted in “Christopher Langdell: The Case of an ‘Abomination’ in Teaching Practice” by Bruce A. Kimball from Thought and Action: The NEA Higher Education Journal (download PDF here)]In varying contexts, yet strikingly similar ways, this is what a budding or midcareer business student learning from a case tries to do, is something that experienced business decision-makers value, and is something a historian, or anyone else, will often do to round up and harness usable insights from the past.

Interestingly, academic leadership in the interdisciplinary field of business history has long resided less in departments of history or economics than in schools of business and management. Three of the most prominent business history journals in the United States (Business History Review, Enterprise & Society and Journal of Management History) are edited by business school professors. The U.K.-based Association of Business Historians is headed by a business school professor, as is the Business History Society of Japan, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. The profession is attempting a major reshaping of research and teaching agendas to better address 21st century business environments, where large, vertically hierarchical corporations no longer enjoy the dominance they widely possessed throughout the late 19th and most of the 20th centuries. Wharton management professor Daniel Raff authored the lead article How to Do Things with Time, in a recent scholarly forum, seeking to articulate new directions in business history.

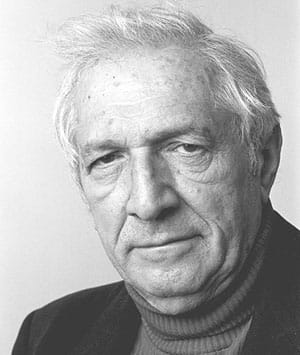

Prof. William Gomberg, who worked for over two decades for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union before becoming a professor at the Wharton School. Photo credit: University Archives Digital Image Collection.

When I was a Wharton student in the late 1970s and early 1980s, one of the most popular MBA classes was William Gomberg’s seminar in Managerial Philosophy and Social Demands on the Corporation. The course had a strong historical dimension and provided an appealing contrast to finance, marketing and other curriculum staples. Understanding and being responsive to the societal environment are part of a corporate manager’s tool kit, and similar material can be found in nooks and crannies of the course offerings of business schools today.

Beyond its long-term contribution in managerial skill-building, however, business history also has tangible relevance to more immediate business activities. Skill at business, like the mastering of history, is more an art than a science, and the historian’s craft—locating and interpreting past information—is essential to developing a credible business plan, adhering to a viable marketing strategy, communicating with potential investors, and promulgating a strategic vision for partners, executives and employees.

How radically different from the technical mechanisms used by contemporary, forward-looking business endeavors, yet how similar to some of the core tasks facing them, is this assignment listed on Professor Gomberg’s course syllabus for BA 925, Spring 1980: “A written review, not to exceed three double-space typewritten 8 1/2 by 11 sheets, reviewing the weekly material from the point of view of its impact upon the future.”