Flashback: June 2008. Pat walks in the pristine boardroom with a stern face, a look of confidence. Today is the day. The deal will either be finalized or fall through. Pat retrieves the BlackBerry from its holster and places it on the table. The symbol of success, the pinnacle of serious business, encompassed in that unassailable device with the familiar physical keyboard.

At that time, BlackBerry’s stock was soaring at $144.56 per share. But the more interesting part is what having one conveyed about you. A BlackBerry user was a serious go-getter, business person extraordinaire.

Fast-forward: Jan. 9, 2014. The stock closed at $8.72. The company had cut 4,500 jobs and took a $4.4 billion quarter loss on Z10 unsold devices and inventory commitments. Seventytwo percent of consumers in a 2013 survey by research house Raymond James agreed, “Nothing would get me to buy a BlackBerry.” Thorsten Heins is out, and now it’s John Chen’s turn as CEO . He makes a 2016 promise of profitability, offers a new BlackBerry plan with a focus on “iconic design, worldclass security, software development and enterprise-mobility management.”

Oh my, how things have changed!

I study “Identity Loyalty”—the curious case when brands become a part of consumers’ self-identity and consumers connect deeply with a brand’s values, use the brand to express who they are, sing the praises of the brand and defend the brand with fervor. One really interesting aspect of BlackBerry’s amazing rise to greatness, and its current challenges, has to do with the social psychological takeaways that exist from a branding perspective. They can perhaps inform those who are in charge of shepherding a turnaround.

The Fools Gold of Focusing Only on Product Features. Sure, you have to have a product that works. But that’s really the easy part—or maybe I should say the part that is necessary but somewhat insufficient. The other path is to build something into that product to tell a story about why consumers should use your brand to self-identify and communicate a shared sense of values to other consumers. Take, for example, the Nike Swoosh. Most of what Nike does is to talk about what the product means, a story of the celebration and empowerment through sport. That’s brand marketing. Consumers see the Swoosh and immediately generate the cohesive associations that create the meaning behind the brand.

Creating an Identity and Creating a Category. Apple is another iconic company that created a lifestyle, an emotional story to shroud the brand and enhance its product features. There were many MP3 players in the marketplace in 2001. Creating a digital music store was important to attract customers, but so was a story about those little white ear buds— and creating a category—through the brand’s identity—a story about the person using them: creative, fun, interesting and social. This was not an MP3 player but an “iPod.” Think about that. This difference existed purely in consumers’ minds, but it created a powerful psychological distance between all those “other” products. The same positioning was used for the iPhone. There are smartphones and then there are iPhones.

I know you are but what am I? When focus is too much on features, it often allows your competitor to define who you are. Even some of the world’s most successful companies have found themselves in the crosshairs of those competitors. Apple did this to Microsoft superbly. Before Microsoft knew it, Apple had messaged the idea that the Apple user was creative, hip, young, fun; PC’ers were archaic, stodgy and boring. When Microsoft finally countered with the message, “I am a PC,” it was already working from a psychological deficit. Rather than being able to have cart blanche to create its own identity, Microsoft had to counteract what Apple had already established for it.

Among the teachable moments here for BlackBerry: It is critical to proactively create your own brand identity, to control your own internal narrative about your brand’s why and its personality—before your competitor does it for you.

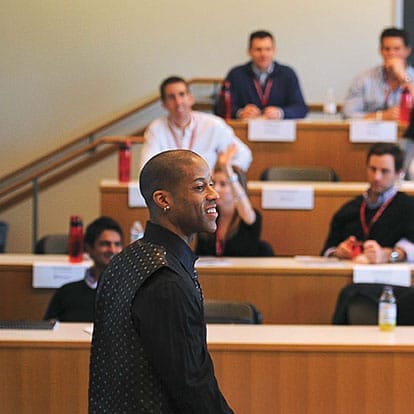

Watch it: Our video “Professor Americus Reed II: In a Minute,” in which the Wharton School’s Whitney M. Young Jr. Professor of Marketing and “Brand Identity Theorist” explains how companies, products and people need to create a unique image—much like he does for himself.

It is also important to understand that when new brand identities emerge, you must evaluate what they are and be nimble enough to reposition your own identity over time. For example, the Droid brand split the difference between creative and media intensive on one end of the spectrum of identity and serious business professional on the other. With Droid, consumers do not have to choose from either end of the identity spectrum. In some senses, the positioning change that resulted from a third option may have contributed to the erosion of BlackBerry’s brand identity.

Another lesson is that product features do not translate to brand identity. I get nervous for BlackBerry when I read statements in the press about focusing on enterprise mobility management, software and BBM. These are features. The brand had epitomized the “corporate business identity,” but this has changed. Now is the time to redefine their “why.”

The road to BlackBerry redemption is a long and hard one. My advice for BlackBerry—and any organization attempting a rebound—is to think deeply about purposeful creation of a brand identity that consumers can faithfully use to help them better express who they are, or want to be.

Americus Reed II is the Whitney M. Young Jr. Professor of Marketing at the Wharton School, where he has served on faculty since 2000. An avid fitness enthusiast, part time drummer and tireless educator, Americus’ primary research and consulting areas are in brand equity and Identity Loyalty. He teaches customer analysis, branding and consumer psychology to undergraduate, graduate, doctoral and executive students.