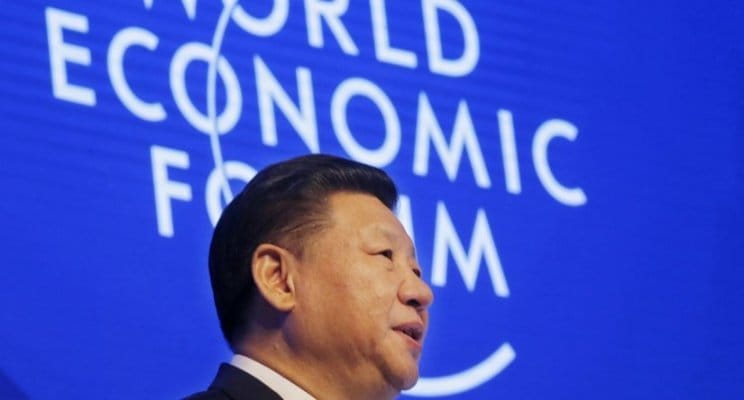

I am at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where China’s President Xi Jingping just spoke in defense of globalization and subtly rebuked any move toward protectionism—reinforcing the reality of his country’s truly global status and stature—a few days before and a continent away from Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th President of the United States.

Trump’s National Economic Council head, Gary Cohn, will no doubt be in Washington, not Davos. Cohn was a WEF regular when he was president of Goldman Sachs. But in the age of “Americanism, not globalism,” neither Cohn nor any senior Trump representatives will make the trip to Davos this year.

America’s inward turn, plus China’s assertive globalism, is likely to be a major theme at Davos this year. It also promises to largely define global affairs in the years ahead. More important, I suspect, than Russia, Putin, NATO, ISIS and the other early foreign affairs headlines of the Trump era.

Much of the world is worried about the big changes in China and the U.S., above all in Asia.

What do these five countries (Australia, Japan, the Philippines, South Korea and Thailand) have in common? They have all been security allies of the United States since the end of World War II, and continue to rely very heavily on Washington for their security. But for all of them, China has emerged as by far their largest trading partner—and the biggest driver of their future prosperity more generally.

American diplomats tend (in private) to look down their noses at China, saying while the reach of the Chinese economy is impressive, China has no real friends in Asia. In contrast, the U.S. has many friends—none more striking than communist Vietnam, which is much more concerned today about the security of its long border with China than the legacy of the Vietnam War with the U.S.

Most of Asia has deftly made China’s rise “both/and” not “either/or” with respect to the American security guarantee. With Trump’s improbable election last November and Xi’s inevitable re-selection for a second term later this year, this balancing act is poised to get much harder.

For a sobering assessment from an American perspective, see Evan Feigenbaum’s excellent piece in The National Interest last month—saying even before Trump enters office, the U.S. is in its weakest position in Asia since Nixon went to China more than 40 years ago.

My recent trips to Asia are consistent with this view.

I was in Manila the week Philippines President Duterte told President Xi of his intended “separation” from America. While the Filipino business and government leaders I talked with tried to downplay the fighting words of their loose-lipped populist president, they quietly told me that they are concerned the U.S. would not defend them in a South China Seas military conflict with China, and that China’s aid + investment + infrastructure economic diplomacy is impossible to resist.

If this requires bad mouthing the U.S. and befriending China, maybe that isn’t the worst outcome. Things are not so different in Australia.

A few weeks after Trump’s election I was in Sydney, where the “time to dump America and embrace China” fervor was running hot, largely drowning out the insistence of prime minister Malcolm Turnbull that the U.S. remains Australia’s most important relationship.

Australia and the Philippines, just like Japan, Korea and Thailand, literally owe their freedom to the U.S. But World War II ended 70 years ago, and they know China is central to their future prosperity. Of course, many are worried about Xi’s geopolitical ambitions. But they are also worried about Trump’s “America first” agenda.

It is in this environment that diplomacy will matter a lot. The reality is that China has been extremely effective in recent years in using economic diplomacy in Asia to get closer to countries that remain wary of its geopolitical ambitions. The Obama “pivot” to Asia was supposed to counter this, but the results have been very disappointing.

Consider three new Asia-Pacific economic institutions: The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

TPP is a free trade agreement pushed by Obama to write “the rules of the road” for the Asia-Pacific economy in the 21st century. China is on the outside looking in, with the U.S. in effect saying: If you want to drive on our road, you have to follow our rules.

TPP would have died with little fanfare if Hillary Clinton had won in November. Now its demise in Washington is likelier to be gorier and louder. Make no mistake, this will be a real black eye for the U.S. in Asia because TPP was always more about geopolitics than economics, and because some Asian countries joined not because they wanted to, but because the U.S. wanted them to.

AIIB is a China-led development bank, on the World Bank model, but focused on the massive infrastructure needs of emerging Asia. Better infrastructure is essential to unlocking the full potential of the region, but it also is a great way for China to export its great high-speed rail and ship building infrastructure and to build more connectivity between China, the rest of Asia and ultimately Africa and Europe too (the “One Belt, One Road” initiative).

Obama opposed AIIB, said the U.S. wouldn’t join, and told America’s friends in the region not to join too. In the end, everyone—with the single exception of Japan—ignored Obama and joined the AIIB, and the early returns on the bank are uniformly positive.

RCEP is a China-led free trade grouping of almost all the nations of East and Southeast Asia. The U.S. is on the outside, with no apparent path to inclusion. RCEP is much looser than TPP, with China saying implicitly there are lots of Asian roads to success that don’t require American rules to be effective. While TPP’s future looks bleak, Asian enthusiasm for RCEP is only growing.

So the economic diplomacy scorecard in Asia reads China = 3 (with one U.S. own goal) and U.S. = 0.

Now enter Trump.

It is inevitable that the new administration will make some very loud noise about China—questioning the “one China” policy when it comes to Taiwan; labeling China a currency manipulator (even though the RMB has appreciated more than 30% against the dollar since 2005, and even though the Chinese government is currently trying to prop up the currency, not let it devalue); and imposing tariffs on American imports from China (even though this will hurt American consumers, and even though global supply and distribution chains render bilateral policy largely irrelevant.)

I think and hope this won’t result in an all-out American trade war, much less military conflict, with China—which would be disastrous for both sides, and for the world. I am comforted by the fact that the Chinese “get” and discount Trump’s style, mainly because they use it themselves, i.e. talk tough, do some strong things, but always be willing to cut a deal behind closed doors.

But I also believe Trump should do more. His Asia policy can’t only be China-bashing. He must chart a positive course too.

The first step is likely to be some sort of economic deal with China. Policy economists would love a US-China FTA and/or a US-China Bilateral Investment Treaty. Trump seems allergic to such formal agreements, but perhaps he can fashion an informal deal that would include much of the right content without the legal formalities.

Then he will need to go regional. Trump’s clear preference is for bilateralism, and there is lots of scope for more agreements with different Asian countries. But China has moved to regionalism, and the U.S. needs to follow suit or risk being at minimum left behind, at maximum left right out. TPP was a (misguided) step, in my view, in that direction. But something positive has to rise from its ashes. The most ambitious plan is FTAAP—a free trade agreement binding both sides of the Pacific. That is likely to be a bridge too far, but something like a revived APEC might be more within Trump’s comfort zone.

All this will take years to play out. Asia is not a “crisis” for the U.S., and American foreign policy notoriously runs from one crisis to the next. The changing structural reality of China’s global rise is rarely a crisis. And no one should wish for a real US-China crisis.

But China is bound to be a more front burner issue under Trump. He is right that America has been losing ground to China, but less at home than in Asia. One irony of the new administration is that Trump may be in a better place to reverse this than Hillary Clinton would have been.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published on Dean Geoffrey Garrett’s LinkedIn page, where he was named an “influencer” for his insights in the business world. View the original post here.

Geoffrey Garrett is Dean, Reliance Professor of Management and Private Enterprise, and Professor of Management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Follow Geoff on Twitter.