The world’s largest display of partisan fireworks is about to explode. In less than five weeks, two Southern cities will burst with banners, balloons, brass bands and roll calls. On August 27, 50,000 Republicans will kick off their national convention at the Tampa Bay Times Forum. A week later, a similar number of Democrats will convene in Charlotte, NC.

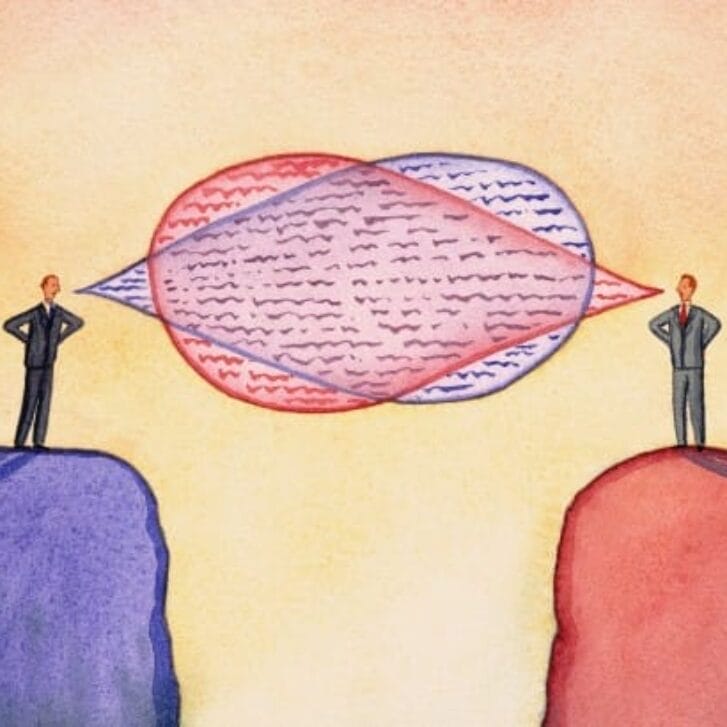

Whether you’re a dispassionate sideliner or a committed participant, you won’t be able to avoid the constant intramural debates. Individual factions will struggle to achieve agreement, even within their own parties. It is no surprise then that after the election the two opposing parties won’t find a way to agree with each other. What makes compromise so difficult?

In her recent book, Amy Gutmann, president of the University of Pennsylvania, offers an answer. Titled The Spirit of Compromise, it’s a far-reaching insight that all attendees at the national conventions, regardless of party, might well heed. With co-author Dennis Thompson, she identifies the block that keeps them, and our nation, from reaching consensus. The culprit is the political campaign. The book’s subtitle—Why Governing Demands [Compromise] and Campaigning Undermines It—states it right on the cover. Campaign promises work against the very spirit of compromise, the authors say. Clearly, the tighter the parties cling to their promises, the more difficult it will be to compromise later, when they return to the business of legislation.

Dr. Amy Gutmann, president of the University of Pennsylvania

Are Gutmann and Thompson suggesting that the parties should rule out bold commitment to their cherished beliefs? Not at all.

“Campaigning is an essential and desirable part of the democratic process,” they write.

Politics has always bred contentiousness. Demonstrations, social movements and activist organizations like the Tea Party are part of the democratic process.

But while the authors see campaigning as essentially good, they also identify its major shortcoming: It never ends. With constant media coverage, it intrudes upon government and encourages an uncompromising mindset. Instead of a willingness to sacrifice one’s interests for the common good, politicians fall into a mindset reinforced by the permanent political campaign. It’s an outlook characterized by mutual mistrust and an obstinate tenacity to party principles.

A flexible and practical mindset, in contrast, provides fertile ground for the classic compromise. It’s an attitude that respects opponents and displays a willingness to subvert its interests to a higher purpose. The authors cite the Tax Reform Act of 1986 as a classic compromise that provided something favorable to each side. Yet each side had to sacrifice something to get what it wanted. Democrats closed loopholes for special interests and the wealthy. But they had to lower the top tax rate from 50 percent to 28 percent. Both sides displayed an underlying conflict of values, but gave up something to improve the status quo.

Before they leave their respective Southern cities intent on a November sweeping victory, delegates might seriously consider Gutmann’s advice: Partisan dominance is not the way to eliminate gridlock. Compromise is. It’s difficult, but governing without it is impossible.